By Jan MacKell Collins

By Jan MacKell Collins

“Jack Haverly, Jack Haverly I wonder where you are. Are your fortunes cast with Sirius, or ‘neath some kindlier star?” – “Memories of Jack Haverly” by Eugene Field, the New York Times circa 1901

We all know certain people in our lives who never seem to hold onto their money, no matter how much they make. During the 1800s, Jack Haverly was just such a person.

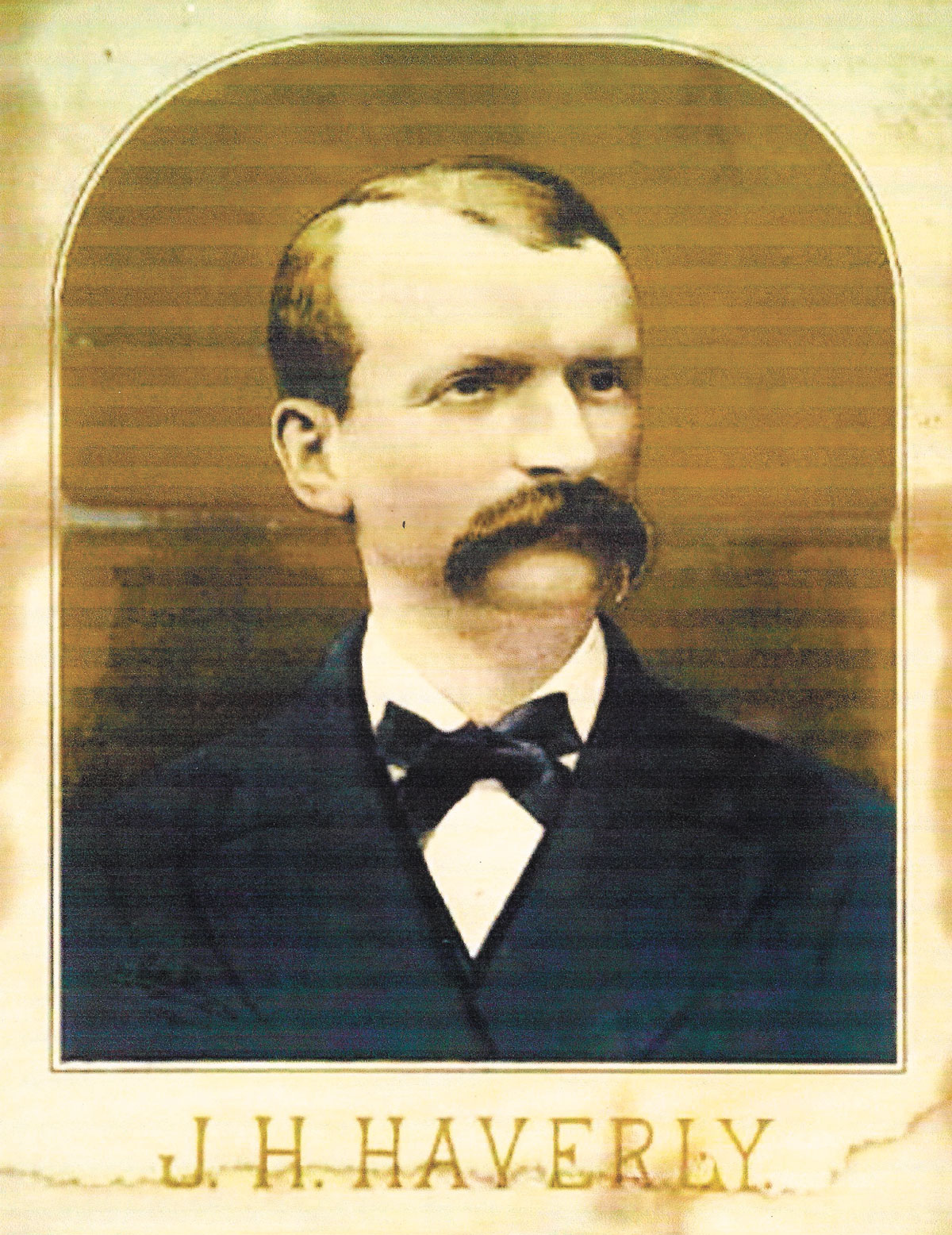

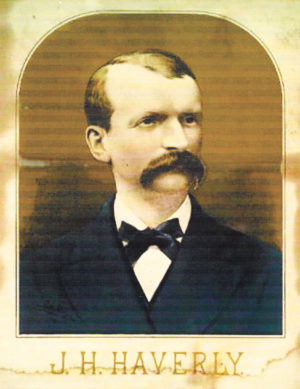

Born Christopher Heverly in Pennsylvania in 1837, the budding capitalist first began working his way up in the world by selling peanuts and candy on passenger trains. He went on to work as a “baggage smasher” for the railroads and also as a tailor’s apprentice before finding where his heart truly belonged: the theatre.

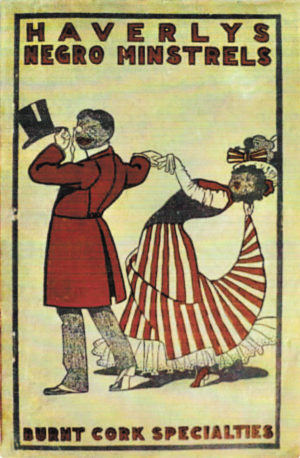

Haverly’s first variety theatre, complete with a saloon, opened in Toledo, Ohio in 1864. As it turned out, Haverly made a great showman. His first performing troupe at the theatre, “Haverly’s Minstrels,” drew record crowds. A misspelling on a poster changed his last name, and he became known in entertainment circles as Jack Haverly.

Shortly after Haverly’s Minstrels debuted, Haverly acquired various partners and began taking his shows on the road. His travels took him across America and north to Canada. Along the way he married one of his showgirls, Sara Hechsinger of the famous Duval Sisters. When Sara died in 1867, he married her sister Eliza.

For over a decade, Haverly bought and sold numerous theaters and headed up an amazing thirteen performing troupes. He seldom had trouble finding investors, even as he became known as a compulsive gambler and speculator who sometimes threw his money away as quickly as he made it. He also had a bad habit of filing for bankruptcy, yet somehow always managed to stay afloat. Newspapers lost count of his failings and resurrections, but his friends never hesitated to loan him money when he needed it. They knew he would pay it back the next time fortune smiled upon him again.

Indeed, Haverly was described as “a fine man and a lovable character” by his friends. “None did more for minstrelsy than he,” applauded his obituary, “and some of the greatest names in theatricals were once associated with him.” In 1877 Haverly created his best show yet, “Haverly’s United Mastadon Minstrels.” The troupe merged four of his most successful blackface shows into one glorious cavalcade of forty performers. By 1880, the Mastadons were even performing in London.

As the Mastadons gained world fame, yet another troupe, “Haverly’s Church Choir Opera Company,” toured Colorado. The group performed Gilbert and Sullivan’s “H.M.S. Pinafore” in Greeley, Central City, Denver and Leadville. The latter town especially was enticing to Haverly, who viewed mining as a new opportunity to make money. More than a few were surprised when he suddenly announced he was tired of showbiz, and wanted to invest in mining.

As the Mastadons gained world fame, yet another troupe, “Haverly’s Church Choir Opera Company,” toured Colorado. The group performed Gilbert and Sullivan’s “H.M.S. Pinafore” in Greeley, Central City, Denver and Leadville. The latter town especially was enticing to Haverly, who viewed mining as a new opportunity to make money. More than a few were surprised when he suddenly announced he was tired of showbiz, and wanted to invest in mining.

True to his word, Haverly sank some money into Leadville’s mines and began exploring the state in earnest. Within a short time he discovered, and grew very fond of, the Gunnison country. When the census taker came around in June of 1880, Haverly could be found at the mining town of Tomichi where he worked as a miner. Eliza wasn’t with him, but he did have two roommates: miner A.C. McDill and a carpenter named H.W. Hutchison.

Haverly’s new career was not lost on the paparazzi. “Jack Haverly, our eccentric theatrical manager, bought something like a thousand lots and a neighboring ranch in May for $30,000,” reported one newspaper, “and could probably double his money by their sale now.” The ranch was just east of Gunnison, and Haverly was far from finished. “This region is probably the only one in all Christendom where ten- and twelve-foot holes sell frequently for from $100,000 to $200,000,” observed one writer, “and Jack Haverly is one of the kind of men who are captured by ‘big croppings.’”

Next, it was reported that Haverly had purchased a promising claim adjoining the Ruby Silver Mining and Smelting Company some thirty miles from Gunnison. Although he had yet to make any developments, Haverly hired a well-known and experienced prospector and set about organizing his very own mining town.

The local miners watched Haverly warily, surmising that a traveling man who cavorted with actresses hardly knew about the labors of mining. “Take a man from his line of business and place him in a business entirely foreign to his own,” warned the mining camp of Irwin’s Elk Mountain Pilot, “and he will surely make a wreck of it.”

Haverly paid no heed, blazing ahead with plans to sell lots at his group of claims. Sales looked promising as local papers reported upwards of 4,000 people flowing into the Ruby Mining District. “Haverly was called foolish,” one writer recalled, and gleefully noted that the lots Haverly paid little for were now selling for thousands.

Throughout 1881 Haverly continued investing in silver mines at Gothic and Irwin, purchased several more ranches and a sawmill, and continued selling town lots. But there was so much going on that miners often confused the town of Haverly with the towns of Ruby, Ruby Camp and Silver Gate. Nearby Irwin, whose post office had opened in 1879, was already threatening to overtake Haverly.

The confusion about Haverly trickled down to those who had purchased claims there. Soon, they were squabbling over who owned what claim. Some began speculating whether Haverly was nothing more than a promotional scheme. The rumor spread, and almost overnight, the forty or so new inhabitants “jumped” the town and left Haverly’s founding father out in the cold.

Most of the investors left Haverly with nary a penny. Haverly himself would claim that he lost some $250,000 on his Colorado mining investments. Thankfully, he remembered that he loved theatre best and hastened to resurrect his performing minstrels. In no time at all, he was managing sixteen minstrel shows and opera companies, with offices in Boston, Chicago, Denver and New York. Jack Haverly was back on top.

[InContentAdTwo] As late as 1885, George Crofutt’s Grip-Sack Guide to Colorado noted that Haverly “is the last name, so far as we are informed, for Ruby, Ruby Camp, Silver Gate, etc. in the Ruby Mining District.” The town remained separated from Irwin “by a villainous bit of road”, but the two gradually grew together just as everyone predicted. At last, only Haverly Station, a separate place from Haverly’s town, remained on the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad east of Gunnison.

Haverly’s theatre companies continued performing in grand style for nearly fifteen years before the mining bug bit him again. This time it happened in the Cripple Creek District, which looked mighty attractive when Haverly visited in 1896. But poor Haverly merely staged an exact repeat of the Gunnison debacle, investing in area mines and forming his own namesake town once again. Roughly a hundred miners and several saloonkeepers converged on the new Haverly within just four days, but the veteran investors of the district didn’t bite. Haverly’s second town failed even more quickly than the one in Gunnison, and was soon just a faint memory.

Haverly quickly returned to showbiz once again. His minstrel troupes toured extensively until 1901, when he finally succumbed to some longtime heart problems. His body was shipped back to Pennsylvania as newspapers across the country paid tribute to the flamboyant theatre man who had entertained the country for decades. Today, theatre history buffs fondly remember Haverly’s minstrel shows and opera companies, while two towns with the same name have faded into the past.

Jan MacKell Collins is busy rambling around the West like a freakin’ gypsy. More about Jack Haverly can be read in her book, Lost Ghost Towns of Teller County.