Article by Kirt J. Boyd

Local History – May 2005 – Colorado Central Magazine

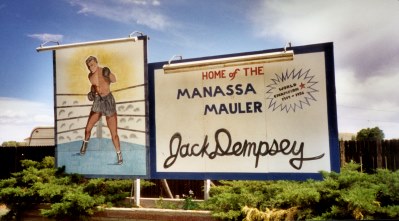

ON JULY 4, 1919, in Toledo, Ohio, 20,000-plus fans watched Jack Dempsey destroy Jess Willard, and become heavyweight champion of the world. By the end of the third round, Jack had broken Willard’s jaw, knocked out six of his teeth, and closed one of his eyes. Many people lost money that day, not believing that a fighter 58 pounds lighter than Willard could possibly win.

Bat Masterson, who was probably bitter after betting on Willard and losing, wrote that a champion should have a bigness and presence, and predicted that Dempsey wouldn’t last six months as champion, He was wrong on both accounts. Dempsey remained champion for seven years, and proved that size doesn’t matter when you have a fighting heart and a punch that ends fights before they start.

While his life after he became champion was filled with movie deals, flashy clothing, and money, Dempsey spent his early years fighting his way through Colorado mining camps, often receiving nothing but cuts and bruises for his trouble.

Dempsey’s interest and later success in boxing isn’t surprising. His brother Bernie, twenty years his senior, was a prizefighter, and his grandfather, Big Andrew Dempsey, had been a West Virginia regional boxing champion. Jack’s determination and stubbornness can be traced to his great uncle, “Devil” Anse Hatfield of the Hatfield and McCoys. But, ultimately, he had his mother to thank. He may have started boxing because of Bernie, but he became champion because his mother said he would.

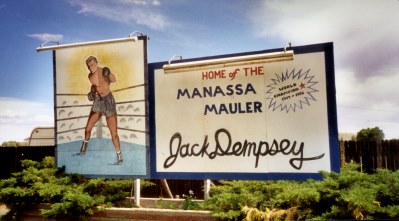

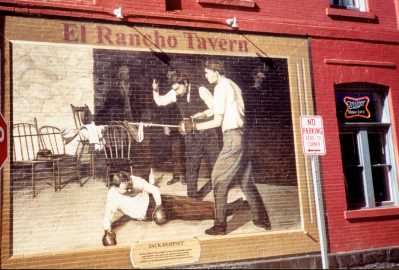

Before his birth in Manassa, Dempsey’s mother had read and reread Life of a 19th Century Gladiator, a biography of John L. Sullivan, the great bareknuckle champion. When William Harrison Dempsey — he wouldn’t fight under the name Jack Dempsey until 1913 — was born on June 24, 1895, she announced that he was going to grow up and be champion, just like John L. Sullivan.

Dempsey first learned he could punch when he was growing up in Manassa. When he was seven, he got into a fight with a boy named Fred. During the fight, Fred’s father urged his boy to use his teeth. When Fred, obviously shocked by the suggestion, turned to his father, Dempsey hit him so hard he had to be revived by the local veterinarian.

Dempsey’s brother Bernie was largely responsible for his success, both then and up until he was champion. Besides giving his brother boxing tips, he gave him a taste of what real fighting was all about. After the family moved to Uncompahgre in 1907, Bernie let his brother tag along when he went looking for saloon fights in neighboring towns. Dempsey was fascinated by what he saw. The ropes were usually made out of clothesline, and the gloves, if any were available, were often crusty with dried blood. He loved watching Bernie fight, even though he sometimes took awful beatings. Witnessing those fights confirmed that he wanted to be a fighter, just like his brother.

WHEN THE FAMILY MOVED to Montrose in 1909, Dempsey started training seriously with his brother. Bernie had told him stories of fights being stopped because of simple cuts and instructed him to bathe his face and hands in beef brine to toughen the skin, something he continued to do throughout his career. To strengthen his jaw, Bernie had him chew tree gum. To develop speed, he skipped rope and chased horses up and down Main Street. Before long, he was ready for his first prize fight. He was thirteen. The fight was against Tommy Pitts, one of two boys Dempsey regularly squared off with. The prize was two chickens. “I won the fight,” Dempsey later said, “but you’d never know it if you’d seen my face.” He would also win his first professional fight several years later.

After graduating from the eighth grade in Provo, Utah, Dempsey returned to Montrose to start his boxing career. His first professional fight took place at the Moose Hall against Fred Wood, The Fighting Blacksmith. Dempsey fought under the name, Kid Blackie. Bernie had been fighting as Jack Dempsey, after the great middleweight of the eighteen eighties and nineties, and suggested that his brother use a ring name like Kid Dawson or Kid McCoy. Dempsey decided on Kid Blackie because of his dark hair and complexion.

AFTER THE FIGHT was set, Dempsey sold tickets on the street for twenty-five cents apiece. He trained for the fight in an old shed in back of Fred’s father’s blacksmith shop. He built a cage inside the shed, roughly the size of a ring, but only four feet high, forcing him to shadow box in a crouched position, which he hoped would make him harder to hit and enable him to deliver harder punches.

The training paid off. The first two rounds were even, but in the third, Dempsey let loose and landed a wild haymaker that sent Wood face down in the sawdust. They made forty dollars for the fight. It seemed like Dempsey was on his way, but he soon learned that it wouldn’t always be that easy. Over the next several years, Dempsey risked his life on the rods, traveling from one mining town to another, working when he could, and fighting anyone willing.

Between 1910 and 1915, 25,000 railroad trespassers were killed. Many towns had hobo graveyards for the unfortunates who fell to their deaths after clinging to the cowcatcher on the front of the engine, or balancing on the couplings (which were commonly called the “death woods”) between the cars. Dempsey preferred to hang onto the narrow, steel beams that ran underneath Pullman Cars. On cold nights, when he was in danger of literally shivering himself to death, he would secure his hands and feet to the beams with light chains or cloth.

Over the years, Dempsey learned that the fastest trains were the ones that transported perishable goods, followed by the mail trains. And he learned to read the towns by their cigarette butts. Long butts meant prosperity; short butts meant hard times. Dempsey took any job he could find. He picked fruit, worked in the mines when he could, shoveled manure, and sometimes went door to door, asking for work. “I never turned down a job anybody offered me,” he later said, “no matter what the pay.”

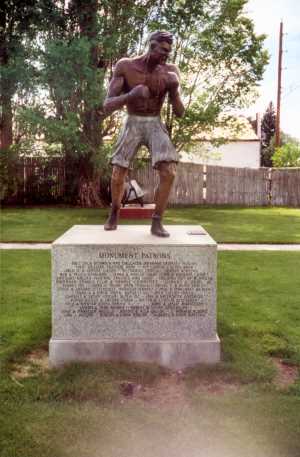

TO SECURE FIGHTS, Dempsey would walk into the roughest saloon he could find and announce, “I can’t sing and I can’t dance, but I’ll lick anybody in the house.” This was usually met with laughter because of his high-pitched voice, inherited from his father, and his small stature. His top fighting weight was 190, but at the time he only weighed about 145 pounds. Although most didn’t take Dempsey seriously, there were always one or two willing to risk their reputations by squaring off with a loudmouthed kid. Other times he would ask the bartender if there was anyone who gave him and his patrons trouble. If there was, and there always was, Dempsey offered to fight the bully and split whatever money they made when they passed the hat.

Dempsey had a simple philosophy when fighting much bigger men: If he hit them on the chin and they didn’t blink, he’d hit them in the stomach. If they stil1 didn’t blink, he’d run like hell. Most of them blinked.

For one of the most taxing fights of his career, Dempsey made nothing. In the spring of 1913, Bernie, now approaching forty, was scheduled to fight George Coplen, a seasoned boxer and mine worker, at the Lyric Opera House in Cripple Creek, but Bernie decided to back out after learning that George had once sparred with Jack Johnson. Bernie sent for his brother, who was spending a brief time with his father in West Virginia.

WHEN HIS BROTHER ARRIVED, Bernie told him the situation. Dempsey goaded Bernie for backing out, but agreed to take the fight. But he was tired after three days of riding the rails, and wanted to rest. Bernie wanted him to train, and he also wanted him to fight under the name, Jack Dempsey. On fight night, his brother found out why: Bernie hadn’t bothered to tell the fight’s promoter about the substitution.

When Jack climbed into the ring instead of his brother, the promoter was furious and threatened to stop the fight. Coplen agreed, stating that he might kill the younger Dempsey. The fight eventually started and Dempsey floored Coplen six times in the first round. The fight should have been over, but Coplen always managed to get to his feet. And worse, he seemed stronger every time he got up. Coplen went down twice more in the second round, but nearly ended the fight with a roundhouse to Dempsey’s ear.

Dempsey later recalled that he thought the building had blown up under his feet. By round three Dempsey was having trouble breathing, and by the end of the sixth, he was near exhaustion and considered quitting. What drove him to finish, he said later, was his unwillingness to disappoint his brother. In the seventh round, his chest covered in Coplen’s blood, Jack lashed out and put him on the canvass two more times. And again, Coplen got up. Moments later, Jack knocked him down for a third time, and watched, horrified, as Coplen started pulling himself up by the ropes. Coplen was down for good, though. The referee stopped the fight and announced Jack Dempsey as the winner. When they went to collect their money, the promoter told them that he hadn’t placed any bets on him because he wasn’t even supposed to be fighting.

One of Dempsey’s stranger fights occurred in a livery stable in Olathe. Big Ed, Olathe’s local strongman and wrestler, agreed to box Dempsey in a winner-take-all bout set up by Dempsey’s manager of the time, Andy Malloy. Dempsey had recently beaten Malloy in an exhibition match in Durango. It was the third time Malloy had fought Dempsey and lost. After the bout in Durango, Andy decided it was safer to manage him. It should have been an easy fight, but before it could start, the town marshal walked in and informed Dempsey that he didn’t permit boxing in his town and that he would have to wrestle Big Ed. Dempsey refused, but the marshal threatened to throw them in jail for an unpaid boardinghouse fee if he didn’t go through with it. Dempsey spent the next three minutes having his legs tied in knots and being thrown from one end of the ring to the other. Later, in 1931, Dempsey got his revenge on a wrestler named Billy Edwards who learned the hard way that you don’t take a swing at the referee.

One of Dempsey’s last fights in Colorado was in Salida against a 200-pound machinist named Hector Conrew. Dempsey had just gotten back from New York, where John Lester Johnson broke three of his ribs with one punch. Dempsey was working as a janitor for Laura Evans, a woman who ran houses of prostitution on Front Street. The fight was held at The Rink, a combination dance hall and roller-skating parlor. Dempsey let Hector hit him a couple of times in the first and second rounds, but in the third, he turned to Laura, who was seated in the first row, and asked her when she wanted him to put this guy in her lap. “Well,” she said, “I am getting tired,” Moments later, fol1owing a clinch, Hector lost his balance and Dempsey delivered a punch that sent him through the ropes and onto Laura’s lap.

Over the next three years, Dempsey fought his way up the ranks, eventually beating Carl Morris, Fred Fulton, and Billy Miske, and earned a title shot against Willard. Before the fight, Willard had the audacity to ask Dempsey’s manager, Doc Kearns, for legal immunity in case he killed Dempsey. Perhaps Willard would have benefitted from hearing the words of a Salida resident who said, “When Jack Dempsey socks you, you stay socked.”

Kirt J. Boyd is a boxing fan and history buff in Denver.