by Michael L. Bullock

Personally, I had no problem filling out and returning my family’s 2010 U.S. Census questionnaire – my wife took care of it.

But as a newly unemployed Colorado newspaperman in January of 2010, I took the bait. It was hidden within the pages of the local paper: “Help wanted. 2010 U.S. Census enumerators. Temporary.”

Unassuming John Doe that I am, I trotted over to the American Legion Hall and took the exam. And I passed the test!

At first, anyway.

What I learned in the next six months of field operations for the United States Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration Census Bureau was totally unexpected. That’s because I had no expectations at all when I first hired on.

“What kind of critter is this U.S. federal government?” I wondered. I had never worked for that outfit before.

I would soon learn that our government of the good ol’ USA is a curious contraption constructed by committee, and that it has as little knowledge of Americans as we have trust in Uncle Sam.

Welcome to The Census

My mission as a crew leader assistant for the U.S. Census Bureau was to help count folks in Central Colorado. It began with administrative training on a snowy February day in Pueblo.

What we newcomers first learned at training was that everyone present was in training. The trainers were hired a short time before us, their trainers a short time before them, and so on up the chain of command. No federal employees were to be found on the premises. Oh yes, we were all now federal employees, but apparently this census taking would consist largely of regular folks interrogating regular folks.

Our leader cordially welcomed us and called roll.

We next took our oath of office, swearing to uphold the U.S. Constitution and protect the pie.

Say what? Protect the pie?

I raised my hand and soon learned that the PII was Personally Identifiable Information: any and all census documentation that links information to identifiable people. We were to protect this at all costs, lest we jeopardize confidentiality and the public trust.

I was just fine with that.

It was also evident that the federal government runs on a steady diet of abbreviations. I next met the CL for CLD at the LCO (the Crew Leader for the Crew Leader District at the Local Census Office).

We spent much of that first day in a procession of paperwork and curious combinations of numbers and letters on all the forms. Our favorite was the 308. That’s the time card. We crew leaders and crew leader assistants in training paid close attention as the payroll procedure was explained.

Watching the snowflakes fall outside the window, I heard the trainer issue a series of directives beginning with the words: “You can’t …” and “You have to …” Then there came a repeated admonition: “Do not take unauthorized overtime. You will be fired!”

Then abruptly, “No hats during training, please.” I lifted my hand to remove my hat, then I remembered that I wasn’t wearing one.

Finally, as darkness and snow both fell outside, we were told that only one more task remained: fingerprinting. We learned all about fingerprinting. We learned how to fingerprint. We were fingerprinted. We were assured that we would not be fingerprinting the public, only each other.

Well, that was some relief.

As we washed the ink from our hands and grabbed our coats, we were welcomed once again to the 2010 Census.

It was going to be interesting.

Hit the (frozen) streets

Back at home we prepared for enumerator (census taker) training, as a crew of friends and neighbors, to go out and count local folks who didn’t get their questionnaire in the mail. But on the morning before enumerator training I received an official phone call. “Mr. Bullock, you can’t begin enumerator training. The FBI has a problem with your fingerprints.”

I gasped. I thought, “Oh my God! They caught me!” And then I remembered that I hadn’t done anything wrong.

The gentleman on the phone assured me that the Federal Bureau of Investigation would notify me shortly regarding further developments in my case.

They did. Everything was fine. Get to work.

I did.

At enumerator training we learned our jobs through a combination of verbatim readings from the official manual and question-and-answer sessions consisting of asking each other: “What does that mean?”

We census takers were a grassroots organization, employed hourly, to help Uncle Sam determine who all was living where on April 1, 2010: Census Day. Under the long and loose reins of the federal bureaucracy, we were guided to the moment of truth – when we were told to go out and begin interrogating the public. And to use our own vehicles.

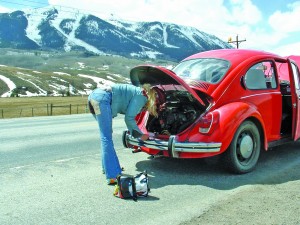

Off into the frozen streets and mountains we dispersed, census maps in hand, to distribute questionnaires door to door and ask some questions. This went fairly well, because most folks in rural Colorado are relaxed and cordial. But the February snowdrifts on Forest Service roads and long private driveways were a problem.

“I have finished my area and have only this stack of undeliverable questionnaires,” I proudly informed my local supervisor, handing him the pile. “These addresses are inaccessible,” I explained, adding, “and I have noted that on the forms.”

Good idea. Bad result.

For days we returned back up the chain of command the census surveys intended for unreachable snowbound buildings, until the local crew leader and I received an urgent directive.

“Do not send back uncompleted questionnaires marked ‘Inaccessible!” commanded the e-mail from HQ.

“Inaccessible is not an acceptable status.”

The crew leader and I stared at each other for a moment, then I muttered in response, “Well, you metro folks sure are invited to come up here and deliver these.”

A sizable boulder slightly buried in a snowy mountain driveway ended the work day for one enumerator, and her car. No, the Census Bureau would not pay to replace the ripped-out drive train or the towing charge, she soon learned.

I recalled President John Kennedy’s words: “Ask not what your country can do for you …”

And we met people. American people. Some live in beautiful homes; some live in buildings on wheels; some sleep in shacks.

We waited patiently at front doors where invalid residents took a while to get there.

We were greeted by angry faces and angrier voices, as some residents allowed us to hear their messages of hate of the U.S. government.

A rancher on his tractor stopped to deal with us. Someone else slammed the back door at his house and took off in his car. A realtor sped her vehicle up close to us as we walked up the driveway of a vacant house, one of hundreds of vacant houses (should we send those surveys to the mortgage banks?).

And much loneliness was evident, where isolated residents wanted to talk and talk and talk. In English y Español. Gracias, it’s time to go.

In a constant exchange of paperwork and supplies, enumerators rendezvoused in parking lots and convenience stores, cafes and bars, homes and offices. Meanwhile, the bureaucracy above us fired off e-mails 24/7, alternating praise for our efforts with outrage at our improprieties.

Mountains of paperwork grew higher and deeper.

We continued our rounds with a cheery, “Don’t forget to mail back your questionnaires!”

NRFU

Many folks did not mail back their questionnaires. Go figure. Some just plain refused. The second Census operation, as springtime slowly arrived, was NRFU (pronounced “narfoo”), Non-response Follow-up. The refusers were the non-response; we enumerators were the follow-up.

“Excuse me, sir. The U.S. Constitution requires a national census every ten years.” We carried a list of convincing things to say. “Your response is required by law.”

Some of their objections had us stumped. “If this is just to count people where we live, why does the government need to know who was just visiting at my house on April 1, and whether I spend time in jail, and whether I own my house, and my age and my race?”

I tried to be upbeat. “I don’t know, sir. Let’s mark the box that asks who lived here on April 1, and go hit and miss on these others, OK?”

We were just trying to do our jobs, we assured everyone.

Some were not convinced. Like the pit bull that greeted one enumerator with multiple bites requiring stitches. Like the residents who took the opportunity to show off their firearms. Like the reclusive country folks who preferred that outsiders did not get too close to their unusual farming operations.

As the Census rolled up its sleeves to take on the more resistant segment of our population, I was beginning to see a more military face on the operation. “We are forming a SWAT team to go after this neighborhood,” one crew leader informed me.

I wondered: what special weapons and tactics might those be?

As summer 2010 approached, I was beginning to understand what kind of critter this U.S. government is. It is an enormous bureaucracy in which: authority prevails over reason, everything not forbidden is mandatory, and the head doesn’t know what the foot is doing.

It is an excellent plan in Washington that becomes a chaotic boondoggle in the hinterland.

It is a beleaguered business trying to stay afloat financially while spending more money than it brings in.

It is a dream of democracy in action, and a reality of dysfunction and public enmity. And the animosity is non-partisan. Anger at the U.S. government spans the political spectrum door to door.

Coercion, confusion. Comedy.

The Senseless Bureau.

Yet I take my hat off to the men and women who have been laboring this year to pull it off: to identify who we are as a country, and where we live.

If Americans and the U.S. government are to cooperate as associates and not clash as antagonists, communication and consultation cannot be only a decennial exercise.

As a fellow enumerator put it, “It’s amazing that we still have a federal government.”

As The Census Goes Rolling Along

The bureau and I parted company in July, as field operations wound down and the census shifted more to data processing. U.S. unemployment figures spiked as tens of thousands of census workers were terminated, as they say.

We rank-and-file census takers were aware that we had relied on Uncle Sam, and the taxpayers of this country, to keep us employed for a while during these hard economic times.

Thank goodness for the 308.

I recall the words of one crew leader, who shook his head back and forth in bewilderment. “The Feds ought to just pay $50 to everyone who mails back their questionnaire. That would be cheaper than hiring all of us to track it down.”

It was heartening to witness the friendliness and understanding of most Americans. It was alarming to witness the ineptitude of the federal government in action.

It was puzzling that our people and our national government behave like distrusting strangers.

As census workers we learned that approaching strangers made us feel more at home, anywhere.

The 2010 U.S. Census is winding toward its conclusion, as all that information gets sifted somewhere. I say thanks to the United States Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration Census Bureau for the job and the enlightenment.

Hopefully, the United States depicted by the 2010 Census will be a country we recognize, and still believe in.

Hopefully, we remain a people worth knowing.

Finally, I offer this tribute in song (sung to the melody of “As the Casons Go Rolling Along”):

Over hill, over dale,

let us hit the dusty trail,

as the Census goes rolling along.

Padlocked gates, 308s,

everyone abbreviates,

as the Census goes rolling along.

John Doe’s mad as hell,

and he’s not too proud to tell.

“Sir, we’re just trying to do our jobs!”

And yes, it’s so:

the U.S. needs to know,

as the Census goes rolling along.

Buena Vista resident Michael Bullock is former editor of The Chaffee County Times newspaper, and currently teaches English at Colorado Mountain College. Hoping to retire after a distinguished newspaper career, Mike instead is gainfully employed to maintain a steady supply of Power Bait and fish hooks.