Essay by Ed Quillen

Migration – December 2005 – Colorado Central Magazine

FOR MY BIRTHDAY a few years ago, one of my daughters gave me a T-shirt, which I wear — even though I believe there should be a federal law against transporting T-shirts that don’t have pockets across state lines, since a shirt pocket is one of the most useful of human inventions.

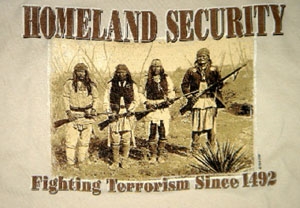

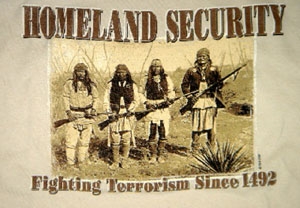

But even though my birthday shirt is pocketless, it bears a 19th-century photograph of Geronimo and three other Chiricahua Apaches, dressed in tattered garb, all holding rifles and displaying stares that convey “don’t mess with me.” Below the picture is the caption: “Homeland Security. Fighting terrorism since 1492.”

Despite what our federal constitution says about free speech, this is not a wardrobe I would recommend to anyone planning to board an airplane. It also raises some questions, not just about what “Homeland Security” might mean, but also about migration.

The Apache, after all, were immigrants to Arizona. Most historians say they began, as a distinct people, in western Canada.

But they moved south in about 1000. By the 17th century, the Apache dominated Colorado’s eastern plains. They were then pushed south by the Comanche, a northern tribe that moved this way after their enemies acquired guns from French traders.

Eventually the Apache split up — one division became known as the Navajo Apache and then just the Navajo, while other bands became known as the Chiricahua, Lipon, and Mescalero Apache.

So in historic times, when Gen. George Crook was pursuing them in Arizona, was it really their “homeland” that they were trying to secure? When you consider how migrant we humans really are, is there really such a thing as a “homeland” — that is, a place where one’s ancestors have lived since time immemorial, with its own traditions, culture, language, government, cuisine, etc.?

This issue seemed to be an “elephant in the room” at the annual Headwaters Conference in Gunnison this year — that is, an issue that people talked around, but never directly addressed.

Humans being what they are, almost everybody is a migrant — but some, of course, arrived first. The Apache and Ute arrived before the Spanish; the Spanish came before the Arapaho; the Arapaho came before the ’59ers; who came before most ranchers; who came before Greek and Italian railroaders; who came before hippies and yuppies and second home owners.

At Headwaters there was a lot of talk about helping immigrants assimilate, but is that what migrants are supposed to do? Were the Comanche supposed to assimilate with the Apache? Were pioneers and prospectors supposed to join up with the Arapaho and Cheyenne?

And who’s supposed to assimilate with who? A student at Headwaters said he’d lived in an Indian village in southern Mexico for awhile and he would rather assimilate with the Mexicans than vice versa. He thought they lived better and more environmentally – by growing their own food, not rushing around, and enjoying the little things.

THIS YEAR’S Headwaters Conference was supposed to be about “the American Dream,” with an emphasis on how it effects the two groups of immigrants who are currently coming here in search of it.

One group comes up from the south, primarily Mexico, with the idea of working hard and improving their living conditions, either here or back home. The other group comes from east or west, with the idea of building a dream home in scenic country and enjoying the fruits of success.

The conference focused almost entirely on the first group, which actually isn’t very different from earlier groups of American immigrants — even to the political controversies they inspire.

In the early years of the 20th century, local newspapers in Central Colorado were worried about the influx of Italian immigrants. They would work hard for low wages, thus taking jobs away from real American labor. Often they sent money to their families back in the Old Country, where they planned to return, and so they weren’t really planning to become real Americans. They had their own grocery stores and restaurants. They weren’t Protestants and they stuck to themselves in their own churches and schools. Sometimes they had their own newspapers, which indicated that they weren’t in any hurry to learn English and become good Americans. They didn’t abide by American laws like Prohibition. They had criminal mobs and gangs.

Anti-immigrant sentiments grew so virulent, there was even a vigilante reaction — the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, which managed to dominate Colorado’s state government for two years after the 1924 election.

In short, just about everything that Tom Tancredo (the Littleton Republican who represents Colorado’s sixth congressional district in Washington) says about Mexican immigrants today was said 80 years ago about Italian immigrants.

BUT TODAY ANTAGONISM toward immigrants from southern Europe is largely an historical curiosity. Salida has a fair-sized Italian population, and in 27 years here, I’ve heard some bigoted talk about other minorities, but nary a word about the Italian immigrants of yore, whose descendants own businesses here and hold public office and form an integral part of our community.

Despite the dire warnings back then, they didn’t destroy the American Way of Life. They became part of it. So I’m dubious about some of the hysterical talk regarding Mexican immigrants. After all, I’m sitting in what was once Mexican territory as I write this. In the war of 1846-48, America came to Mexico, and the current boundary between the two nations is an artifice of politics, not a result of geography or culture. Indeed, some of us have joked that no matter where they draw the line on the map, in some ways Mexico starts at Poncha Pass.

But it’s easy for me to take a longer view. I’m not one of those people who is likely to lose his livelihood to an immigrant (or for that matter, to have his work done in India, as happens in the tech sector.)

On account of my columns in the Denver Post, though, I have received emails whose general tenor goes something like this:

“I’m a carpenter in a growing metropolitan area. There’s plenty of work to be done. But on the last four jobs, I was the only American citizen on the crew. All the rest were illegals. They know their work and they work hard. But how much longer am I going to be able to work before I’m replaced by cheaper immigrant labor? Is my own government doing anything to protect me?”

PROBABLY NOT. That’s the screwy part of our two-party system. You see survey after survey which says that about 70 percent of Americans, including a majority of Hispanics, want the United States to crack down on illegal immigration. But it continues more or less unabated, and it often appears that the federal government is just going through the motions, if that.

It divides both parties. President Bush has proposed a “guest worker” program for Mexican workers, and American companies are always looking for ways to reduce labor costs. But many members of his own party don’t want more Mexican immigrants allowed into the United States, period.

On the Democratic side, there’s the humanitarian sanctuary faction, with the argument that we are obliged to our fellow humans, no matter where they happened to be born. And then there’s organized labor and the law of supply and demand. The welfare of the working stiff is tied to wages and benefits. The greater the supply of labor, the lower the wages and benefits. Immigration increases the supply. So if you want to help working families in this country, you’ve got to eliminate the unfair competition from illegal immigrants.

But Democrats aren’t as beholden to organized labor as they once were, and there’s an ethnic or racial component here. You can sound like a bigot if you complain too loudly about immigration, and no Democrat wants to sound like a bigot.

Thus neither party is going to take any real action because, in grossly oversimplified terms, the financial support of the Republican Party comes from people who want cheap labor, and the emotional support of the Democratic Party comes from people who oppose bigotry and discrimination.

And any realistic crackdown on illegal immigration would involve plenty of bigotry and discrimination. Think about it. Our border with Mexico is 1,951 miles long, wending through mountain and desert. We don’t have the resources to make that totally secure. People will always be getting across it.

So perhaps our government should do more to discourage employers from hiring illegals?

But how would you feel if your family had been living hereabouts since about 1850, and because you had dark skin and brown eyes and black hair, you had to produce half a dozen documents every time you changed jobs? Is this the way a “free” country should treat its own citizens?

And won’t “going after employers” inevitably encourage them to discriminate against employees who don’t have blue eyes – in order to be on the safe side?

I CAN’T THINK OF any simple answers to America’s immigration problems. And no one else seems to be able to, either. That’s why it’s a matter of contention.

And if we go back to Geronimo, we get more questions about the meaning of immigration. For instance, in 1868 the United States signed a treaty with the Utes, guaranteeing them a fair chunk of the Western Slope for as long as the rivers flowed and the grass grew.

But then gold and silver were found in the San Juans, and American prospectors rushed in. They were trespassers. Or in modern parlance, “illegal immigrants.” Just like the ones Tom Tancredo warns us against, they were going to bring their own way of life: adits, stopes, stamp mills, railroads, newspapers, all the rest. They weren’t moving into Ute territory with the idea of adopting Ute customs. They weren’t going to assimilate.

Was that immigration? Or invasion? And what of the modern immigrants in search of the American Dream? Are those people building a 10,000-square-foot seasonal mansion really immigrating with the idea of assimilating, and thus fitting in with the rest of us who worry more about our woodpiles than our non-existent investment portfolios?

I seriously doubt it.

If Tom Tancredo has the right to worry about neighborhoods where there are carneterias and panaterias replacing butcher shops and bakeries on account of immigration, should we worry about small towns where there are crystal shops, galleries, Realtors, and high-end bicycle dealers where there used to be hardware stores, drug stores and feed stores?

In either case, we’re talking about cultural and economic shifts brought on by immigration. Your town is going to change, no matter whether the immigrants are poor folks from Mexico or rich folks from California. And it appears that there’s not much you can do about either.

When you get right down to it, I’m not in any real position to complain, even if I often do. I’m an immigrant, too. I wasn’t born or reared in Central Colorado. I grew up on the Front Range. I was part of the 1970s “hippies moving to the mountains migration in Colorado,” and there were a lot of people then who didn’t welcome us with open arms.

WE, TOO, BROUGHT our culture with us — we wanted rock ‘n’ roll, not country music, and bars and radio stations either adapted or saw competitors. Some of us wanted food beyond meat and potatoes (which, by the way, still suit me fine). We wore hiking boots instead of cowboy boots, sported beards instead of crewcuts, rode bikes instead of horses, and this list could go on much longer.

The point is, we weren’t in any hurry to “assimilate,” although as is usually the case when two cultures abide by each other, both make a few changes (and eventually old hippies become modern good-ol’-boys).

When I wonder why I’ve stayed here, I think it’s because I never could assimilate into modern mainstream freeway-ramp America. This area always seemed like a haven, a refuge from that enforced madness.

And I’d like to keep it that way. The Apache doubtless felt the same way about their home, though, as did the residents of mountain towns in the 1970s who wondered what they’d ever done to deserve an invasion of folks like me.

Apparently our homelands can never be all that secure. Things just don’t work that way.