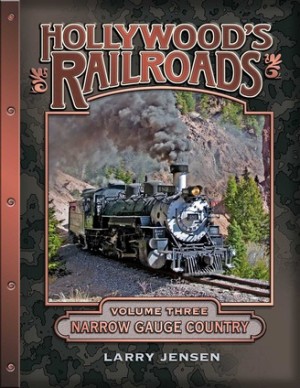

by Larry Jenson

Motion picture directors, producers and writers have long recognized the multitude of possibilities for comedy, drama and suspense that railroads offer. Chases, races, robberies, wrecks, derring-do and intrigue on and around trains provided the kind of excitement that kept audiences coming back for more.

Motion picture directors, producers and writers have long recognized the multitude of possibilities for comedy, drama and suspense that railroads offer. Chases, races, robberies, wrecks, derring-do and intrigue on and around trains provided the kind of excitement that kept audiences coming back for more.

In a quest to find interesting locations, Hollywood filmmakers “discovered” various railroads around the country. The Hollywood’s Railroads book series tells their stories.

For more than 75 years, filmmakers have used the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad and its modern-day successors, the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad and Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad, in dozens of motion pictures that featured many of the industry’s biggest stars.

Hollywood’s Railroads, Volume Three: Narrow Gauge Country takes readers behind the scenes in southwestern Colorado and northwestern New Mexico. The 72-page book is illustrated with more than 130 photos. We are pleased to present here an excerpt from the book. More information on the book series is available at www.CochetopaPress.biz.

THE DENVER & RIO GRANDE WESTERN RAILROAD once operated an extensive system of narrow gauge lines in southwestern Colorado and northwestern New Mexico. Most were built during the early 1880s to serve geographically isolated towns, many of which had large-scale mining and smelting operations.

The railroad was chartered in 1870 by General William Jackson Palmer as a north-south route from Denver, Colorado to El Paso, Texas. His Denver & Rio Grande Railway Company would be a three-foot narrow gauge line, as opposed to standard gauge, which is 4 feet, 8.5 inches between the rails. This unconventional decision would lower initial construction and equipment costs but make it impossible to interchange rolling stock with mainline railroads.

The D&RG completed a 112-mile line from Denver to Pueblo along the Front Range of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains in 1872, along with a 31-mile branch from Pueblo to Florence. Money problems then slowed progress for several years. A 9-mile line between Florence and Cañon City was completed in 1874, followed by a 91-mile line from Pueblo to Trinidad in 1876.

The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe acquired the right-of-way over Raton Pass, south of Trinidad, in 1878, blocking the D&RG from building into New Mexico via that route. The AT&SF also contested the D&RG’s attempt to build west of Cañon City through the Royal Gorge the same year, employing both armed mercenaries and the courts. That route was finally granted to the D&RG in 1880, and it immediately built a 54-mile line from Cañon City to Salida. This line continued on to Leadville, Glenwood Springs and Grand Junction.

The contested routes didn’t stop progress. The D&RG built a 70-mile line from a point south of Pueblo over the Sangre de Cristo mountains to Alamosa, reaching that city in 1878. At Alamosa the D&RG crossed the Rio Grande River, completing the promise of its name.

While the railroad was ultimately completed as far south as Santa Fe, New Mexico, the original objective of El Paso was abandoned in favor of pushing west into the Colorado mountains to take advantage of various mining strikes.

The San Juan Extension was built from Antonito, Colorado, over Cumbres Pass to Chama, New Mexico,in 1880. This line was extended to Durango in 1881 and Silverton in 1882. The D&RG also built west from Salida, reaching Gunnison in 1881 and Montrose and Grand Junction in 1882. Other narrow gauge railroads were built to connect with the D&RG system. Most notable among these was the Rio Grande Southern between Durango and Ridgway, completed in 1891.

In the late 1880s, and on through the 1890s, the D&RG’s more profitable routes were converted to standard gauge, including all of the track on the Front Range, the lines to Alamosa and Grand Junction, and the track between Grand Junction and Montrose. Alamosa, Salida, and Montrose became interchange points for the now-isolated narrow gauge, with facilities to transfer shipments from narrow to standard gauge cars.

In 1901 the D&RG merged with the Rio Grande Western, a sister line that extended from Grand Junction to Salt Lake City, Utah. When the company reorganized in 1921, its name was changed to Denver & Rio Grande Western. During the Great Depression, the railroad acquired trackage rights over the distressed Denver & Salt Lake – which had a superior route into the mountains west of Denver, but failed to reach Utah. It later acquired complete ownership.

The D&RGW – commonly called the “Rio Grande” – became a regional bridge route from Denver to Salt Lake City. In partnership with the Chicago Burlington & Quincy Railroad (which operated east of Denver) and the Western Pacific Railroad (which operated west of Salt Lake City), the Rio Grande offered a competitive alternative to the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific for shipments from the Midwest to northern California.

After World War II, the Rio Grande’s management was focused on its standard gauge operations. The antiquated, labor-intensive narrow gauge lines needed special attention and didn’t fit in with the modern and efficient image the railroad publicized. Management began a campaign to eliminate all of those lines over time. With a shrinking business base due to improved highways and a decline in mining, abandonment was a fairly easy argument to make to the Interstate Commerce Commission on a case-by-case basis. Only a small percentage of the population of the region and a few railroad fans voiced opposition. All of the lines could very easily have disappeared.

Then something unanticipated happened: tourists began discovering southwestern Colorado. Many of them first learned of the area’s scenic wonders in major motion pictures. Claims have been made that Hollywood exposure helped save the line between Durango and Silverton and – to a lesser degree – what is now the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad. This is difficult to quantify. One thing is certain, though: the exposure didn’t hurt.

With its spectacular scenery, Colorado was an early destination for motion picture production companies. In 1897 James H. White of the Edison Company shot numerous travelogue-type films around the state that were two minutes or less apiece. These films focused on scenic wonders and engineering marvels, including some of the state’s railroads.

In those early days, anyone with a camera could make a motion picture. Renown Denver photographer Harry H. Buckwalter began making movies in 1900. His early films were travelogues less than four minutes in length distributed nationally by the Selig Polyscope Picture Company of Chicago, Illinois. In the wake of Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery in 1903 – credited as the first film to tell a story – Buckwalter began telling stories, too. Those films were approximately eight minutes long. He continued to make motion pictures in the state on a regular basis until 1909 and occasionally thereafter.

During this period, various motion picture companies from the East sent traveling troupes to Colorado in search of interesting backgrounds for film stories. A regular presence in the state by an outside company wasn’t established until September 1911, when a Selig Polyscope troupe settled in Cañon City. The troupe produced eight films in 1911 and more than 25 in 1912. Most were Westerns, with some utilizing Rio Grande standard gauge trains. The troupe was reassigned to Prescott, Arizona in January 1913 and didn’t return.

[InContentAdTwo]

Former Selig Polyscope employee Otis B. Thayer was among a group that established the Colorado Motion Picture Company in Denver in August 1913. Cañon City offered incentives for the business to locate there, which it did in January 1914. The company purchased a Main Street building to serve as offices and studio, but made less than 10 movies before ceasing production that fall for unknown reasons. Thayer continued to make movies for other Colorado production companies through 1923. He moved to Hollywood in 1924 and continued his career there.

Movies had long since made the transition from novelty to big business. Corporations monopolized production and distribution and built factories to manufacture films in a climate that enabled year-round production. The first movie studio was established in the Los Angeles suburb of Hollywood in 1911. Within a few years most of the Eastern production companies, including Selig Polyscope, had moved to Hollywood or other nearby towns.

That didn’t deter individuals elsewhere with a dream of getting into the motion picture business. One was James W. Jarvis, a Durango rancher and the town’s Studebaker automobile dealer. He established the Durango Film Producing Company in 1917. His first project, Small Town Vamp, included train scenes filmed at the Durango depot. In 1918 Jarvis made Snow Wonderland, a documentary about keeping the railroad tracks clear of snow on the Silverton line. Neither of these short films is known to exist today. Jarvis made several other films, including the 90-minute Navajo Love in 1921, an interracial love story. He closed the company in 1922 to devote his time to other business interests. In 1925 he assisted producer Frank J. Carroll with Native American cast members in The Scarlett West, another interracial love story shot around Dolores, Colorado. It was the first Hollywood film made in southwestern Colorado.

In the early days of Hollywood, the vast majority of movies were shot close to the studios. As the running time of films increased from a few minutes to an hour or more, and plots became more complex, adventurous filmmakers began going “on location” to utilize scenic backgrounds like raging rivers, rugged mountains and desolate deserts, which didn’t exist near Hollywood. Northern California became a favorite destination, as did northern Arizona.

While a dozen films had been shot in New Mexico between 1898 and the early 1930s, a big-budget Hollywood motion picture wasn’t made around Santa Fe until director King Vidor shot The Texas Rangers there in 1935. That Western included a brief train scene done on the Rio Grande narrow gauge. The next production to headquarter in Santa Fe – director William A. Wellman’s The Light That Failed in 1939 – also called on the Rio Grande for a train scene.

The San Juan mountains in southwestern Colorado remained a remote region with primitive roads until after World War II. A daily passenger train, the San Juan Express, was the only easy way to get there. It ran between Durango and Alamosa, where there was a standard gauge connection to Denver. The train was finally discontinued on Jan.31, 1951, due to declining patronage.

By then Hollywood location scouts were already exploring the area. They liked what they found. In the summer of 1948, director Louis King selected the Durango area for the 20th Century-Fox film Sand, a contemporary Western based on a 1929 novel by Will James. While most of the outdoor action was shot north of Durango and on a ranch near Pagosa Springs, the pivotal train scene that actually sets the plot in motion was done on the Southern Pacific after the film company returned to California.

Robert Bassler, the producer of Sand, took note of what the Durango area had to offer while he was there, including the quaint narrow gauge railroad with its old time locomotives and rolling stock. He would return to use the train and scenery in a film the following year, but he wouldn’t be the first. Word that the Durango region was a filmmaker’s paradise was already circulating around Hollywood.

Larry Jensen has been researching and writing about railroads in motion pictures for more than thirty years. He is a refuge from Los Angeles who has lived in Colorado for ten years.