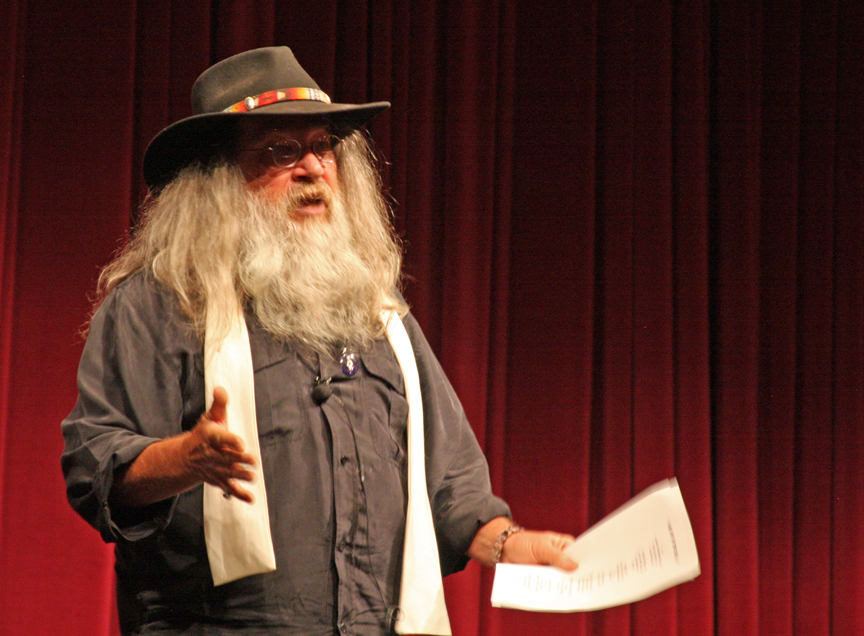

The 25th Headwaters Conference, The Working Wild, began Friday, Sept. 20 at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison. The auditorium was full in anticipation of the keynote speaker, Gary Snyder. One spectator mused, “It’s the gathering of the eagles,” with community leaders from all over the Headwaters region in attendance. After a poem by Art Goodtimes and a song by Alan Wartes, Conference Director John Hausdoerffer introduced Snyder. He revealed that Snyder, a beat generation poet, inspired Jack Kerouac’s famous character from the Dharma Bums, Japhy Ryder.

Snyder began by dissecting the words of the theme: wild and wilderness. Wilderness, he said, came from the Old English words meaning self-willed, beast and place. What does it mean for land to be self-willed, Snyder asked the audience. Wild in Germanic and Chinese, which Snyder studied, meant self-ordered or self-managed. He explained that when he thought of wilderness he looked at the percentage of wild processes. Snyder went on to give a few opinions on land management before moving into reading. He read mostly from Mountains and Rivers Without End, a collection of poetry he had written over the last 40 years. He lulled the audience into meditative stillness as he described white water and rivers, trees and forests, and rocks and mountains. Hausdoerffer said later, “It was like listening to a mountain speak.”

Near the end of his Keynote address, Snyder read from his famous poem For the Children, which ends, “Stay together/Learn the Flowers/Go light.”

The Headwaters Conference was started 25 years ago by former Western faculty member George Sibley. He recalled the years leading up to the Conference during his address Saturday afternoon. He said universities all over the country were struggling after the baby boomers were completing higher ed. He recalled a time when there were talks of turning Western into a medium-security prison. Sibley went to faculty meetings that “he didn’t belong in” to push his idea of a conference. He described thinking that Gunnison was just a few hours’ drive to the start of many major rivers. “We were the headwaters school,” he said. The Headwaters Conference was a way for headwaters communities to gather, network and collaborate.

Saturday’s schedule consisted of three panels, The Private Wild, The Urban Wild and The Common Wild, with readings and tours mixed in. Sean Prentiss began the morning by reading from his not-yet-released Finding Abbey, a book about searching for Ed Abbey’s desert grave, and searching for the legend along the way.

Dr. Corrie Knapp, a Masters of Environmental Management (MEM) professor, moderated “The Private Wild” panel, which consisted of Bill Parker from Parker Pastures, a holistic farming ranch; Stacy McPhail, the director of Gunnison Valley Ranching for Gunnison Ranchland Conservation Legacy; Ryan Atwell, executive director of Coldharbour Sustainable Living Center and MEM faculty; and Bill Trampe, a lifelong Gunnison Valley rancher.

Knapp asked the panel for their definition of “wild.” Most panelists agreed that wild was a something along the lines of a place where natural processes were the majority. Only Bill Trampe said wild no longer exists, and if it does somewhere it’s not in the Gunnison Basin because there’s “too much influence of man.” Developments and recreation have deteriorated the “wild.” Parker said that wild is something that “can’t be controlled or understood.” He added, “wild has to be cultivated,” which, “takes people on the land.” He went on to say soils are healthier on private land.

Parker’s point of wild being cultivated became a major theme that developed throughout the discussion, and that cultivation requires hands-on people who know their land intimately. Trampe shared his struggle of ranching near Crested Butte, where there are so many who are “entitled to play,” and that recreation can interfere with food production. Atwell said cultivating wild needs multidiscipline approaches due to the complexity of these issues. The cultivation of wild isn’t just a topic for rural areas but is also needed in cities.

“The Urban Wild” panel was moderated by Gavin Van Horn from the Center for Humans and Nature, and consisted of Curt Meine, senior fellow of the Aldo Leopold Foundation and Center for Humans and Nature; John Tallmadge, the author of Meeting the Tree of Life and Reading Under the Sign of Nature; Michael Bryson, professor of Sustainability Studies from Roosevelt University; and Laura Watt, professor of Environmental Studies at Sonoma State University. This panel was mostly presentation with little discussion.

Meine, visiting from Chicago, spoke of the connection between cities and wild. He talked about the trend for people to gradually gravitate from urban areas to suburban to exurban to rural to wild, rather than stay and improve the place they are in. The result of looking for a better place is a fallacy because “no part is sustainable if the whole isn’t.” Van Horn, also from Chicago, built upon the first panel by stating the need to cultivate wild in the places where we are. Watt presented a project she’s a part of in the Bay area, working with her school to turn the South Bay Salt Ponds into an urban wildlife reserve.

Bryson spoke about kids being the heart of the urban wild because “kids find stuff.” He said a child’s view is more wild than adults’ because their eyes are on the ground and they’re attentive to their surroundings. Tallmadge also talked about the importance of working with kids to restore wild in urban areas, especially through urban gardening. He said, “To work with kids, you have to slow down and get down,” to see things at their level. He ended the panel with a more philosophical tone by saying, “the universe is the greatest self-organization,” and our challenge is to connect our work with nature.

F

ollowing the morning sessions, attendees chose an area tour ranging from a restoration hike to local foods to green building. After the tours, Aaron Abeyta read from his Letters from the Headwaters, a book of essays Abeyta collected from years of attending the Headwaters Conference. His heartfelt essays challenged readers and listeners to a wider perspective, one including those less fortunate. Then the final panel began, “The Common Wild.”

The panel, moderated by Enrique Salmon of Cal State East Bay, consisted of Devon Pena from the Acequia Institute; Shirley Romero Otero from the Land Rights Council in San Luis, Colorado; and Kirsten Atkins from Crested Butte. The panel discussed the controversy surrounding La Sierra Commons, land east of San Luis that includes Culebra Peak, an important watershed for Acequia communities of Northern New Mexico and the Southern San Luis Valley.

The land was originally part of the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, which gave public access to the land. In 1960 the land was bought by a lumberman, Jack Taylor, who tried to keep people from using the land. In 1981 the case went to court, while Atkins, Romero Otero and Pena recalled protesting the land access. Twice the court ruled in favor of the landowner, but in 2002 the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, giving traditional villages of the Culebra drainage rights to public access of the land. All of the panelists talked about the importance of the decision to indigenous rights. Pena said, “Cultural erosion happens when people are disconnected from the land.”

Sibley ended the day’s events by addressing the Conference. “We’ve barely scratched the surface,” he said, on what the Headwaters Conference could be. “We hope for another 25 years.” In summary, Sibley turned to a table of students and built upon Snyder’s poem, “‘Stay together, learn the flowers, go light,’ and I would add to it, work wild.”

Tyler Grimes is currently studying environmental management at Western State.

Tyler –

Thanks for extending the reach of Gary Snyder’s work and the rest of the conference with this good report!

And also thanks (overdue!) to you and Mike Rosso for hosting & launching this Facebook site for 350centralcolorado.