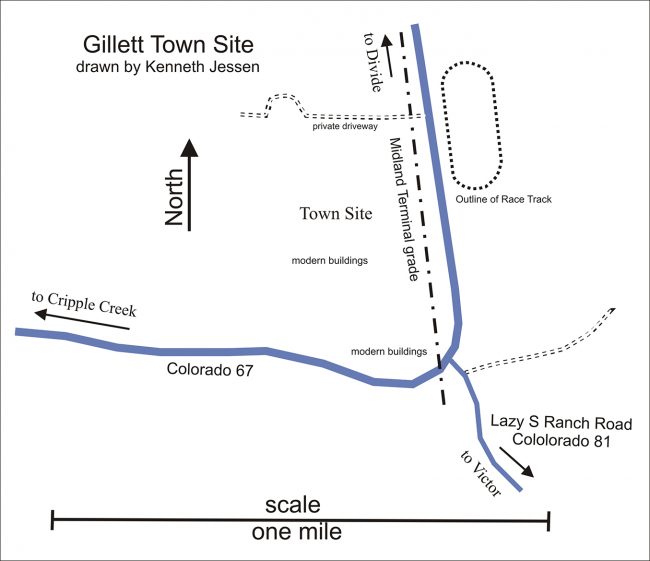

IN TELLER COUNTER, THE ABANDONED town site of Gillett lies just beyond Cripple Creek and Divide, near the intersection of County Roads 67 and 81 (Lazy S Ranch Road). It looks uninteresting, amounting to nothing more than a field with a couple of modern homes near the road.

Gillett began as a simple log cabin. But in anticipation of the arrival of the Midland Terminal Railway from Divide, a land company purchased the valley and filed for a townsite. Originally called West Beaver Park, its name was changed to Gillett upon the arrival of the railroad on July 4, 1894 — the same year that a post office opened. It was named for W. K. Gillett, an officer for the Midland Terminal. A spur was built to access an ore reduction plant to the northwest of the town. Due to the mountainous terrain beyond Gillett, it became a transfer point to Cripple Creek with regular stagecoach service. This arrangement did not last long, since the rails reached Cripple Creek the following year.

With big plans to attract crowds from Colorado Springs, nearby Cripple Creek and Victor, a racetrack was constructed along with a casino. (The outline of the racetrack remains visible on Google Earth.) Gillett had everything — great location, on the way to Cripple Creek, scheduled railroad service. What could go wrong?

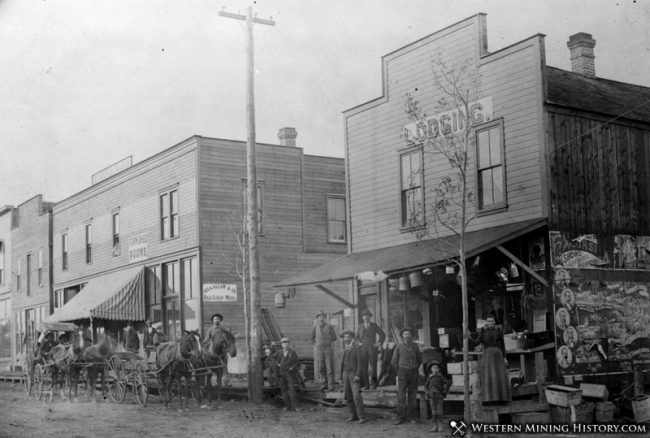

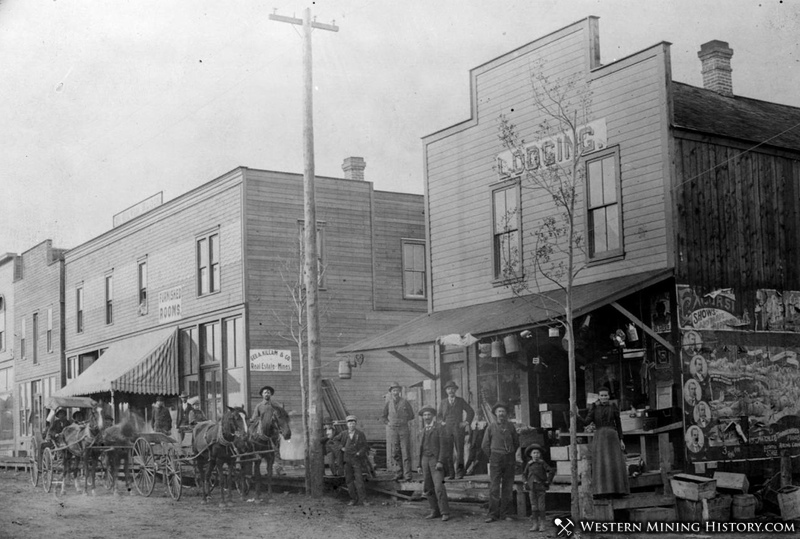

Gillett reached an extraordinary population of more than 1,000. It had an elaborate railroad depot, a substantial business district with long lines of false-front stores and — necessary for a mining town — many saloons, dance halls and a casino.

An unusual story makes Gillett stand out from all other Colorado towns. Cripple Creek Palace Hotel owner Joe Wolfe, with the tarnished reputation of a con man, arranged for a bullfight to be held in Gillett using the racetrack. With a partner, the nefarious “Arizona Charlie” Meadows, he formed the Joe Wolfe Grand National Spanish Bullfight Company. The pair arranged to bring in Mexican bulls, matadors and picadors for the event. However, the promoters failed to take into account action by the Colorado Humane Society: An injunction was issued to stop the bulls from entering the United States. The matadors and picadors were held at the Texas-Mexico border cooling their heels along with the bulls.

As a side note, bullfighting is a cruel blood sport, but it has its roots thousands of years ago. It is, however, part of the culture of Latin countries especially Spain, Portugal and some South American countries. Elements include a stylized slaughter and a slow painful death for the animal. Lances are used in the neck to weaken the muscles and cause the bull to lower its horns. Barbed banderillas are then planted into the shoulders to agitate the animal. A well-dressed matador in an elaborate outfit torments the animal to charge and make passes past his cape. Death comes to the suffering animal when the matador thrusts a sword between the shoulder blades.

In an advertisement on August 17, 1895, in the Cripple Creek Weekly Journal, “The First Ever Given in the United States” proclaimed the bullfight to be held August 24, 25 and 26. It described “a troop of Mexican Bull Fighters and a carload of Fighting Bulls.” World-famous matador Carlos Garcia and a lady bullfighter, La Charitta, were to perform. The advertisement was placed by “J. H. Wolfe, Manager.”

One might imagine the matador Carlos Garcia walking a muddy, manure strewn street in Gillett among dusty, hard-drinking, tobacco-chewing miners. He would be wearing a black velvet hat positioned across his head, an elaborate jeweled waist coat with epaulets and tight-fitting knickers. Below his knees would be traditional white socks. On his feet would have been rather feminine-looking — for the times — leather slippers.

As the dates for the bullfight approached, Wolfe became desperate enough to purchase seven ordinary farm bulls from area ranches, but these bulls weren’t bred to fight. Jan MacKell Collins, in Lost Ghost Towns of Teller County, related that matadors had to put up with these local bulls, coaching them to charge. After being widely advertised, 50,000 people (probably an inflated figure) descended on Gillett. The gore was simply too much; and on the second day, only around 300 showed up. At Wolfe’s invitation, Colorado’s most famous con man, Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith, “worked the crowd,” doing such a good job fleecing the potential audience before the show that a number of seats went empty.

Not surprising, witnesses reported that the bulls were docile, but that several were killed. Another account said that protesters stopped the bullfight after the first animal was slaughtered. In any event, the remainder of the event was canceled. This may have been the only bullfight ever held in the United States or at least in Colorado.

By 1908, only 30 people remained in Gillett, with 60 empty structures still standing; soon the post office closed too. Nearby Cripple Creek and Victor were boomtowns, but Gillett was too far removed from the mines and mills. The valley was purchased for ranching in 1911, and all but a few of Gillett’s structures were razed. The streets were plowed under, and the area was seeded for pasture. The Midland Terminal was abandoned in 1948 and all the tracks were removed. Much of what was left of the town was washed away in a 1965 flood. Looking at the site today, it is difficult to imagine that such a large town once existed.

The structure that survived the longest was the St. Dimas Chapel, with its rounded roof. During the 1940s, ghost town historian Muriel Sibell Wolle visited the Gillett site and described the chapel’s sad condition. Fire gutted the structure in 1952, and today, only rubble and its pillars mark the spot.

Readers can refer to the excellent book by Jan MacKell Collins titled Lost Ghost Towns of Teller County, History Press, 2016. It covers a detailed history of Gillette and the many other interesting ghost towns in the area.

Kenneth Jessen teaches various aspects of Colorado history at CSU, where he is in his ninth year. He is always looking for abandoned places and discovering their history.

Kenneth Jessen is Colorado’s best known historian on Colorado ghost towns. Unlike others, his research is above reproach.