By Christopher Kolomitz

Skiers seem to always go big.

Big air, big adventures and big falls.

And they dream big, too. This year, many are dreaming of massive amounts of snow following a lackluster season last year. More than 30 years ago, developers of two ski areas in Central Colorado were dreaming as well.

Separated by about 80 miles, the Conquistador and Cuchara ski areas share a remarkably similar and sad fate. They were both within a day’s drive of Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma, and no major mountain passes had to be navigated, which was good for marketing. Both were affordable, low key and offered beginners the chance to learn. They were nestled in idyllic valleys, home to historic ranches and scenic vistas.

However, they were cursed with low elevation and poorly oriented slopes. They were miles from major population centers and activity. Management was tangled and finances troubled. At one point both were owned by the government. And in their final days, they signaled the end of small, independent ski areas.

In the Wet Mountain Valley west of Westcliffe, the last time skiers made turns at Conquistador was the spring of 1993. The area employed dozens of people and was paying $56,000 a year in property taxes. Now the base area is run as a Christian camp, although it eerily maintains some of its ski history with a fleet of rental gear from the 1980s jammed into a storage building.

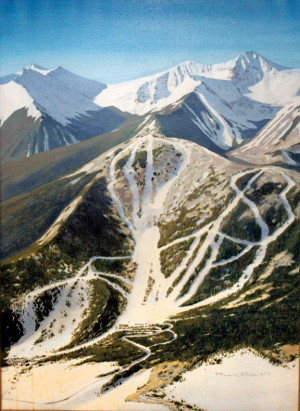

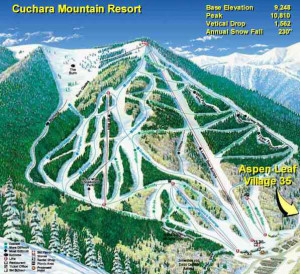

At Cuchara, south of La Veta on Hwy. 12, the property last ran lifts during the 1999-2000 season. It was open 14 seasons, attracting an average of 22,000 skiers annually. But permits to operate on U.S. Forest Service land adjacent to the private property were revoked in 2001. The agency authored a stinging report about future operations and said winter recreation there is not in the public interest. It was listed for sale earlier this fall.

Conquistador

Dick Milstein was the vision behind Conquistador. He spent time getting the Sunlight ski area going near Glenwood Springs in the late 1950s and was a pioneer of international ski racing rules. He died in 2007, and his family held funeral services at the Conquistador ski area.

Milstein and his development team started putting pieces of the ski area together in the 1960s by purchasing ranches and their water rights at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The planned unit development consisted of about 3,000 acres, and was contested by locals who feared the resort would change the valley. Today, there are just a handful of lots with homes around the area.

Its first full year of operation was 1976-77, with just two pony lifts taking skiers up 250 feet. Several lean snow years followed, but Milstein continued with his vision. In 1982 he made a major terrain expansion and installed a new triple chairlift which increased the vertical drop to 1,200 feet. Some of the trails were named after local ranches. There was a snowmaking system and a 36-room hotel on the property, and the day lodge had gone through a major upgrade.

[InContentAdTwo]Milstein’s daughter, Robyn Canda, still lives in Westcliffe. She recalls running the rental shop and selling lift tickets in the morning, and running up to the cafeteria around lunch time to take money. “I’m sure they were tired of seeing me,” she joked. “There was just a lot of heart and family up there.”

However, almost as soon as the expansions were complete, the bank, which gained $23 million in loans from the Small Business Administration for use at Conquistador and other projects, was in default. In late 1982, the SBA took over ownership of the mountain. Milstein was out of the project by 1984.

Several good snow years followed, and attendance was OK, but the SBA was losing $400,000 annually operating the ski area. In March of 1988 the resort closed, and was put up for sale. After several failed attempts to find a buyer, the SBA finally found their man in August 1992 when Mund Shaikly, a California developer, and P.R. McEnhill, a London businessman, purchased 3,000 acres for $3 million.

Shaikly changed the name of the ski area to Mountain Cliffe and initially said he wanted to make improvements to the property under the planned unit development. He was hoping to expand the slopes higher, and create a commercial village. He also considered creating an 18-hole golf course on the property.

By November of 1992, a management team had been hired to run the ski area, and the slopes were open just before Thanksgiving. However, Shaikly and the management team had a falling out in December, the storm track was off, the wind was fierce and temperatures were too warm for making snow. On Mar. 8, 1993, the lifts stopped turning.

In the fall of 1993, Shaikly said he wouldn’t open the ski area for the upcoming winter, and as many as 80 jobs were lost. One thing was going well for Shaikly: more than $800,000 in lot sales were made between June and October of 1993.

The ski area sat vacant until June of 1995, when Paul Zeller purchased 150 acres around the base lodge for $1.2 million. Shaikly kept the remaining property. Zeller, who had long ties to the area, was already running another Christian camp called Horn Creek and said he’d turn the old ski area into a similar camp and conference center. Zeller named it Hermit Basin.

In 2008, Shaikly sold the the water which was used for snowmaking to the city of Fountain and Widefield Water for $3.5 million. The sale of the water with an 1871 right also included a 480-acre ranch on the valley floor.

A surface tow was installed in the early 2000s by the Hermit Basin staff so guests could tube during the winter, although during a tour just a few weeks ago, the tow didn’t look operational. Paul Zeller died earlier this fall, and his daughter Penny and son Jay are saying they plan to keep the camp operation rolling.

At about the same time Milstein was getting Conquistador open, the owners of Cuchara were making their plans, too.

CUCHARA

First opened in 1981-82 as the Panadero Ski Resort, Cuchara was owned by a group of Texas developers who also planned to sell land and housing lots. A total of 130 lots on 23 tracts were created in three different development filings. The original loan was $22 million, and the terrain was minimal, with just four trails covering 350 vertical feet served by one double lift.

The following ski year, 1982-83, saw major expansions and construction of the base facilities with more trails and another double chairlift, which increased the vertical to 1,700 feet. However, the expansion was costly, and by the 1985-86 season the troubles were beginning with the bank starting foreclosure.

Big snow fell in 1986-87, although the area was plagued with poor attendance which followed into the 1987-88 year. By then it was being operated by a savings and loan institution, and eventually a Resolution Trust Company assumed control of the area. Attendance in 1988-89 was better, but the RTC closed the area just a few weeks before the start of the 1989-90 season.

It sold in 1992 for $800,000 to a Texan who operated it for two seasons from 1992-94. Again, poor snow and attendance created financial struggles, which caused the area to close for the 1994-95 season. New owners, brothers from Texas, purchased the base property for $1.8 million and opened for the 1995-96 season with bad snow and low attendance. The 1996-97 season was skipped, although the owners did use the lifts privately without a tram board inspection, which violated the law.

The area was sold again to a Texas group for $2.8 million in time for the 1997-98 season which was marked by a massive blizzard, giving the area the best snow and attendance in 20 years. The rental shop ran out of gear and the once fluffy snow turned to ice.

The owners put $1 million into base area projects and opened for the summer of 1998 and then again that winter, when it switched to a four-day schedule. The base was open for the summer of 1999 and then operated on a four day schedule in the winter of 1999-2000, which was its last.

Since then, the resort has gone through a handful of other owners who have all publicly said they wish to see it reopen. Community owners want it open too, saying the jobs it creates could really help the area.

The current owner is Bruce Cantrell, who purchased the property in 2010 and tried several avenues to reopen. He says the only way it will ever become profitable is to turn it into a year-round resort with a zip line, mountain coaster and other amenities.

Cantrell is a big dreamer with good intentions, but his plans never took off. A metropolitan district was formed but never could get a vote together, he says, because of the shaky bond market. Several nonprofits were formed but never went anywhere due to limited fundraising. He tried partnering with a wounded veterans group, the state and even a local electric association. There was talk about a community co-op running the place but that failed, too.

Now, Cantrell has the 225-acre property up for sale for $4.5 million. The local real estate agent lists the land as a “unique legacy retreat.” Cantrell says the actual ski runs on private property make up about 50 acres with another 175 acres comprising the base area and other property that isn’t a part of the ski area.

Like other former ski areas in the state, many of the runs at Conquistador and Cuchara were carved out of Forest Service land and can still be accessed today. However, that access can be difficult, and the current owners are not always favorable to backcountry skiers who end up on their property.

Christopher Kolomitz is a Salida-based journalist and small business owner. He remembers skiing on ice at Cuchara as a college student.