By Mike Rosso

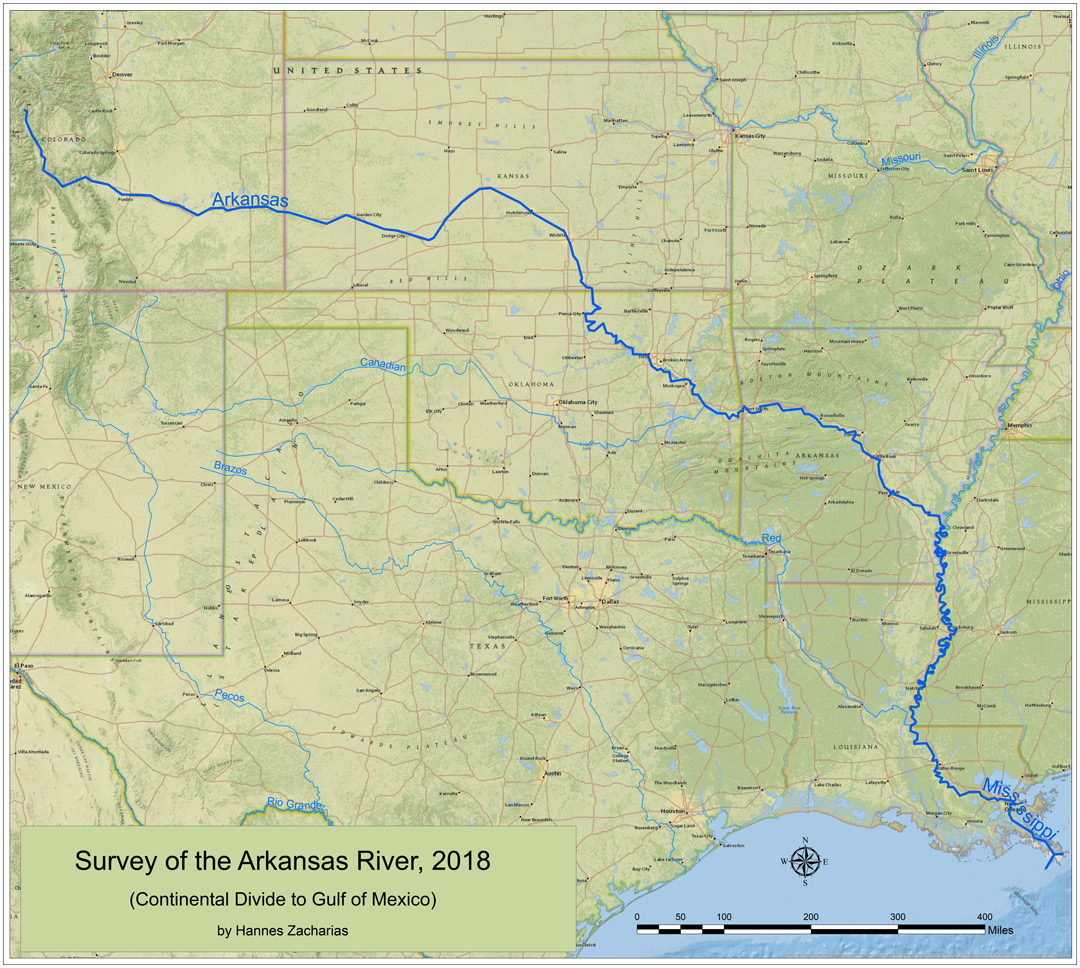

Hannes Zacharias is on a mission. But the 64-year-old resident of Lexana, Kansas is not on just any mission. He is currently in the process of “following a drop of water” from the headwaters of the Arkansas River in Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico.

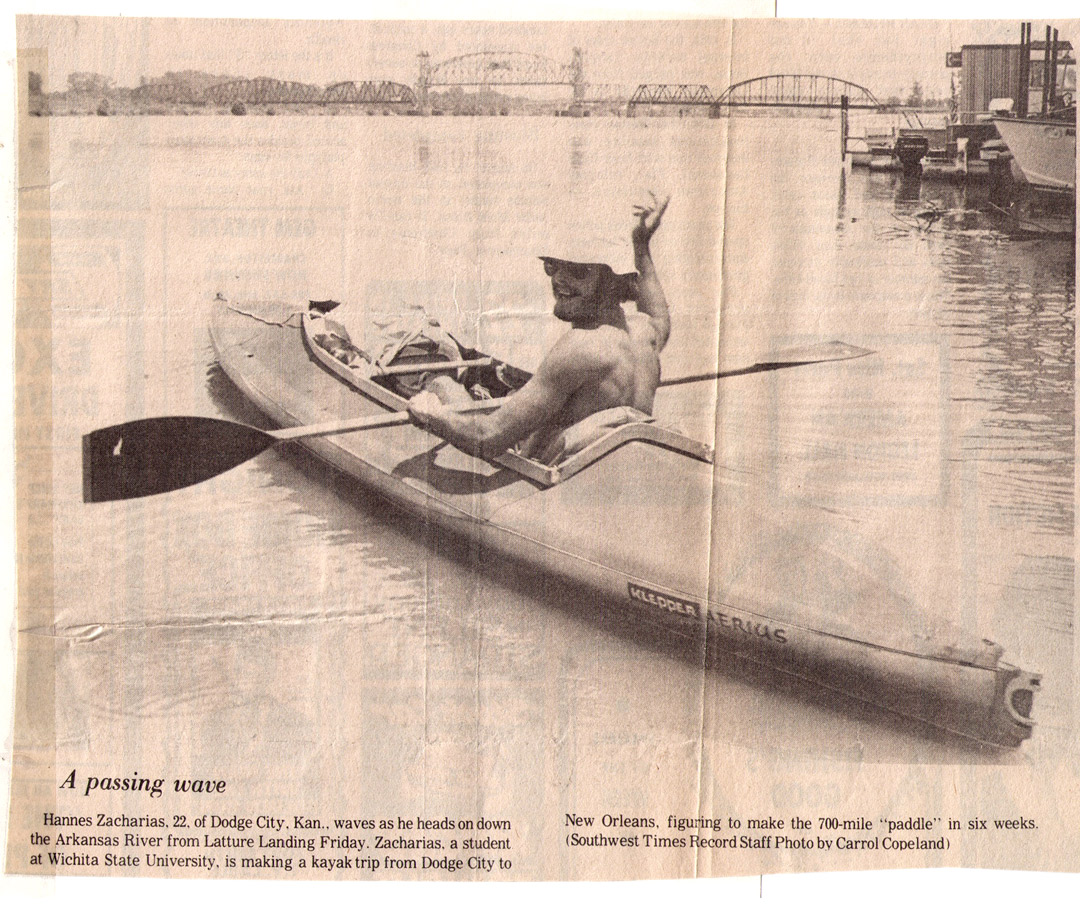

And why would he take on such and ambitious feat? It all dates back to a kayak trip he took in the summer of 1976, at the age of 22. Back then he borrowed the family’s collapsible Klepper kayak and proceeded to “float” the Arkansas from Dodge City, Kansas to New Orleans. He did the trip, “in the spirit of naive adventure and somewhat as a nod to my father’s vision,” said Zacharias, a native of Dodge City.

He began the journey in June of 1976 and completed it two months later in the French Quarter of New Orleans. He carried with him a “bi-centennial” message from the mayor of Dodge City to the mayor of New Orleans and was greeted with a modest fanfare and an honorary key to the city.

“The experience was life-changing,” he said. “I had never been down south before, nor on a river for such an extended time, and had never been totally on my own traveling in a part of the country that had just been violently portrayed in the movie “Deliverance.”

He is now retracing his trip from 42 years ago, but with a more ambitious agenda:

“I want to chronicle the changes over the last 42 years and also document the demise of a portion of the 45th longest river in the world at times, into a barren sand trench (between Pueblo, Colorado and Wichita, Kansas) over the course of one lifetime (mine) … greatly impacting the ecosystem, economy, and social fabric of eastern Colorado and western Kansas as a result of irrigation.”

“I desire to team up with kindred spirits, scholars, and institutions to participate, guide, and advise me on how to make this trip fun, useful and interesting to researchers and the public from an environmental, social and historical perspective,” says the former city manager of Hays, Kansas who has had extensive dealings with Kansas water policy issues. He’s also logged over 800 miles in a canoe on the Missouri River, plus extensive travel on the Kansas River and a sundry of rivers in Missouri, Arkansas and Illinois.

His current plan is to make the 1,469-mile Arkansas River journey, in large part, by non-motorized transport (raft/canoe, walking) in order to “examine present day and historical human interactions with, and attitudes towards, the river, [plus] examining the current condition and environment of the river, comparing it to my 1976 trip and historical references (journals, photographs, relevant scholarly documents).”

The trip is being done in what he calls a “leapfrog” fashion with the help of his Toyota Highlander. Every day, Zacharias assesses his ability to raft, kayak, or hike sections of the river along his journey.

“Each morning I will choose a location downriver to drive my vehicle, pack up my equipment in the car and drive it to the location, then return to the ‘put in’ point (by a volunteer assistant or paid driver) and raft, float, or hike to the car. In this way I will be able to adjust to the changing river levels and weather. At Wichita, I will abandon my car and do the remaining trip by kayak being resupplied as noted in the itinerary.”

But this is not necessarily a solo adventure. Zacharias is using some support personnel along the way to assist with transportation logistics, especially his time from June 6 through July 7. He hopes to begin the Wichita, Kansas to the Gulf of Mexico leg of the trip on July 7 with a conclusion date of September 3.

The total length of the trip is 2,060 miles with 1,469 miles attributed to the Arkansas River and 582 miles to the Mississippi River from the mouth of the Arkansas to the Gulf of Mexico. The anticipated time for the trip is 99 days – May 26 through September 3. Zacharias is developing a two- to three-minute video/report each day, which he is posting on his Facebook page, Hannes’s Ark River Adventure. At the time of this writing, he is in a campground in Lakin, Kansas. One of his observations thus far is how much of the Arkansas River is depleted by ditch irrigation headgates.

“I understand the history of irrigation in the Arkansas River Valley since its beginnings at Bent’s Fort in the 1830s, and water rights in Colorado beginning in 1861. However, it was striking to me that the irrigation system is allowed to take 100 percent of the water, leaving a dry riverbed.

He also noted water quality degradation. “As a result of this trip, I now understand more completely the recycling of irrigation water out of the Arkansas, through the corn and alfalfa fields, and back into the river. What I didn’t fully appreciate is the significant degradation of the river water through this continuous process. While some of the degradation occurred naturally (previous to significant irrigation), the recycling of this water through farm fields significantly decreases the water quality in the river. Evidence of this fact is the need for municipalities downriver to intensify water purification efforts for human consumption. This is driving the increased conversation about the Arkansas River conduit out of Pueblo reservoir to provide better quality water for human consumption throughout the lower Arkansas River Valley.”

[InContentAdTwo] Another observation was that of the “barbed-wiring” of the river. “I understood that limiting access to the Arkansas River was prolific in Colorado. I now fully appreciate this fact in coming across barbed wire at every bridge crossing, bolted to the side of concrete, making access on public right-of-way extremely difficult and hazardous. Additionally, I experienced barbed wire and electric wire being strung across the river. A practice that I understand is illegal, yet continues, and is extremely hazardous to anyone on the river, including those who might be tubing on the river.”

He did note the beauty of the river through southeastern Colorado. “The river is lined with tamarack, cottonwood, cat tails, and a whole assortment of other prairie grasses and flowers. Waterfowl are prodigious in this area, along with a wide variety of other birds. Deer are prevalent in the area and were frequently spooked by my approaching kayak. The river is simply beautiful.”

We will be catching up with Hannes through progress reports and stories in the next several issues of Colorado Central.