by Jan MacKell

“The ancient card faces painted on the layout were doubtless faded and worn but to my boyish eyes they glowed like a church’s stained-glass window … (Gaye) started drawing the cards one by one from the battered old silver box. As he drew, I could see his lips move and knew he was making bets for imaginary customers. Deftly he slapped stacks of chips – we always called them checks – on certain cards of the layout.”

So did Nugget, the main character in Conrad Richter’s book Tacey Cromwell, describe how his brother practiced so he could get a job dealing Faro during the late 1800s. In the old west Faro was more popular than Poker, so chosen because it was amazingly easy to play. Nary a saloon in the West was without it, and several well known figures of the time – Soapy Smith and Doc Holliday among them – made their riches by banking the game.

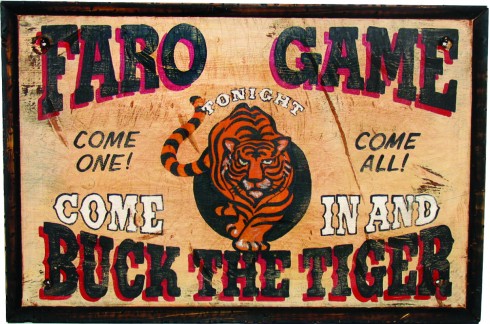

With origins in France during the early 1700s, “Pharoah,” as it was originally called, soon spread to the United States. In America the name was spelled Faro, but was also known as “Bucking the Tiger” due to the picture of a tiger that often appeared on the back of American playing cards. The game consisted of one deck and a Faro board painted with thirteen cards running from Ace to King, plus a square for betting on the High Card. The dealer placed the cards into a “dealing box.” The first card was placed out of play.

With origins in France during the early 1700s, “Pharoah,” as it was originally called, soon spread to the United States. In America the name was spelled Faro, but was also known as “Bucking the Tiger” due to the picture of a tiger that often appeared on the back of American playing cards. The game consisted of one deck and a Faro board painted with thirteen cards running from Ace to King, plus a square for betting on the High Card. The dealer placed the cards into a “dealing box.” The first card was placed out of play.

The rest of the game consisted of dealing the cards one at a time into the two piles. Simply put, the pile on the left lost and the pile on the right won. The numerical order of the cards was unimportant; players placed their chips on the painted cards to bet whether that card would appear in the winning pile. They could also bet on whether the winning card was higher than the losing card. A player could also place a “Copper,” usually an octagon-shaped chip, on any card, to bet that it would appear in the losing pile.

Officially, three employees of the house were required to play Faro: the dealer, who dealt the cards; the lookout, who kept his eye on the bets and made sure the game was square; and the casekeeper, who used an abacus to track the cards as they were played. When three of the same number card (three threes, for instance) had been played, the casekeeper called out “Cases!” When four of the same number card had been played, the abacus beads for that card were arranged so players knew the card was out of play.

The game got more interesting towards the end, since players could bet on the cards that had not been played and increase their odds of winning. The last three cards in the deck were reserved for “calling the turn.” In this final bet, players could call the order in which the three cards might appear. The house paid four to one on these bets, but the odds of winning were purely chance.

As one might guess, Faro was as easy to cheat at as it was to play. Because the game generally moved fast, players could win via sleight of hand tricks, while a seasoned dealer could manipulate the cards to favor the house. In time, even companies that produced legitimate gambling devices also made dealing boxes with a special button that could be pressed to release two cards instead of one. The house increased its odds this way, but the game could still be won by one simple guess of the final three cards. Arguments, fights, shoot-outs, lynchings, lawsuits and arrests soon became a trademark of Faro in the roughest of towns.

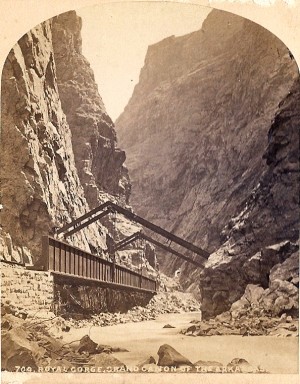

In Denver, Faro made its debut as early as 1860 when Vinton’s Hotel offered $1 stakes in the game. Twenty-two years later, a writer for the Leadville Daily Herald noted that of four gaming tables at the Texas House, two were Faro and “were the most patronized.” By 1890, The Arcade in Denver employed up to nine Faro tables with roughly 40 dealers. In his book Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel, author Jeff Smith (Soapy’s great grandson) reports that the notorious bunco artist spent so much time playing Faro at the The Arcade that “some of his mail was addressed there.”

Like many professional gamblers, Soapy supplemented his career by playing and banking mostly rigged Faro games. Wyatt Earp allegedly dealt Faro in Gunnison during the 1880s. Bob Ford, killer of Jesse James, was dealing Faro at (Old) Colorado City in 1889. Billy Deutsch, a famous gambler of Denver, was rumored to have broken the Faro bank at Monte Carlo during the 1890s. Lady gamblers Minnie Smith and “Poker Alice” Ivers both made their living in Colorado not only at Poker, but also Faro. A popular dime novel in 1902 was Little Miss Millions or, The Witch of Monte Carlo.

In the end, Faro began losing its appeal among gambling houses during the early 1900s. Most veterans of the game could identify crooked dealing boxes and card cheats. A 1937 Record Journal of Douglas County article warned, “Gambling Odds Are Against You” extolling the evils of Faro. By then most casinos had moved on to games of chance that bettered the house’s odds. Only Reno, Nevada was the last holdout, featuring Faro among its table games until about 1985. In time, historians forgot or failed to acknowledge that Faro was once the most popular card game in the West.

The ultimate cause of Faro’s demise? Played fairly, the game gives nearly equal chances of winning by either the house or the players. And casinos in general don’t like that. Indeed, Faro bet – and has lost – in today’s gaming world. Jim Finley, who dealt the game in Nevada for over three decades, mourned the loss of the West’s favorite card game in a 2000 interview. “It’s got a language of its own,” Finley said of the game. “The casinos today aren’t in gambling. They don’t want a game you can win.”

To try a free online version of the game of Faro, please visit http://farolive.com/home.php

A great article, as an American West Reenactor and living history I still find it fun to setup my Faro table at the Buckhorn Exchange Saloon in Denver and play this old west game with customers in the upstairs saloon. Thank you for helping to keep the memory of the American Old west alive. John (Hawkins) Hockley