Column by Hal Walter

Local Life – May 2007 – Colorado Central Magazine

IT WAS APRIL FOOLS DAY, but this is no joke. My father-in-law took his last breath that afternoon, ending his lengthy and courageous battle with cancer as my wife held his hand and his wife and children stood by him. He was 86 and the moon would be full that evening, symbolic of the full life he had led.

Francis Lowell Eickelman was born Feb. 15, 1921, the son of Albert and Margaret (Palmer) Eickelman in Aberdeen, South Dakota. After completing his Bachelor of Science degree in metallurgical engineering at South Dakota School of Mines in 1945, he arrived in Pueblo in 1945 to begin his 37-year career in the steel industry as a metallurgist. He married Rosemary Rajkowski in 1950, and they had six children, including my wife Mary. He retired from the steel business in 1982, but worked as a metallurgical consultant in the rail industry for some time afterward.

During the past holiday season, knowing his time was growing short, he pulled me aside and asked me to write his obituary. He also instructed me specifically to not mention his employer. It was understood that the obituary was for the hometown newspaper, but the least I can do is make sure an expanded artsy version is available in a classy publication like this one.

My father-in-law’s main source of joy was his family. He was a loving and caring husband, parent and grandfather, and I am certain he will be remembered as a gentle and kind man. While Francis may not be the most colorful character I have known, I have to say that his steady, calm demeanor was what really set him apart from just about everyone else I’ve encountered in this life. His openness to new ideas and acceptance of other viewpoints also were exceptional for someone of his generation. And the guy had a real gift for math.

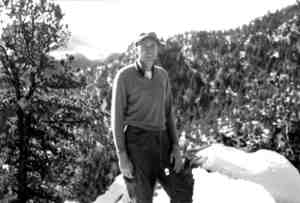

![Francis Eickelman on a Colorado Mountain Club hike in the 1950s, probably on the Highline Trail] Francis Eickelman on a Colorado Mountain Club hike in the 1950s, probably on the Highline Trail]](https://coloradocentralmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/015904611.jpg)

I’m sure that Francis had in mind something different for his daughter than a pack-burro-racing freelance writer/editor/ranch caretaker who wanted to live in the mountains. But he never was judgmental about our lifestyle, and in fact was often supportive of it and inquisitive about it. Sometimes I think he was a bit envious that we had the freedom to make alternative career choices — and that we actually seemed to be getting away with it. He had worked several jobs to earn enough money to put himself through college. But the employer he didn’t wish to be mentioned was the only one he had in his entire career as a metallurgist.

When he was not working, Francis also enjoyed hiking and mountain climbing, golf, bicycling, travel, and exploring Colorado and the Desert Southwest, in particular the Canyonlands of Utah. He was a member of the Colorado Mountain Club and was fond of hiking, especially in the Wet Mountains and Sangre de Cristo Range. In fact, one of the best photos we have of him was taken from the Highline Trail. This trail appears on older topo maps of the northern Wet Mountains, but as best as I can tell it is now partly a logging road and partly lost to overgrowth. It connected to the present-day Lewis Creek Trail, which takes off from the highway just above Wetmore.

Francis was preceded in death by his parents and two brothers. He is survived by his wife, two brothers, and a sister. He is also survived by six children and 11 grandchildren.

——————–

The day before the funeral I went for a run on the Bear Basin Ranch trails. A coyote ran up the hill I was traversing. The first thing I noticed was the coyote’s enormous size — he seemed as big as a German shepherd. The second thing I noticed was that his snout and face were red with blood.

[InContentAdTwo]

I looked around in the brush just downhill from the trail and found a freshly killed doe, maybe two years old. The deer was fat and appeared healthy. Her left eye turned to the sky was still glassy. The coyote had torn open the abdominal cavity and had been gorging on the most nutritious parts — the internal organs — when I disturbed him.

Just uphill from the dead deer was the sign of struggle. The earth had been torn and disturbed. There were patches of deer hair and small pieces of gut. Blood.

But what killed this doe? A mountain lion would likely break its neck, eat the organs and drag it off into the brush to dine upon the muscle meat later. Did one big coyote do this all alone? Maybe so. Or maybe I didn’t see the others.

————————-

I was asked to be a pallbearer, which I was more than happy to do though it made me nervous about my clothing ensemble. The last two funerals I had attended were the type where if you wore a sports jacket with fresh jeans you were almost overdressed. But this would be a big church funeral. Plus, my father-in-law was a firm believer in Mark Twain’s notion that “clothes make the man.”

Actually I had everything lined out from the bottom up. I intended to wear my black Tony Lama western boots, with gray pants, black belt, white shirt, navy-blue tie and gray blazer. However, during a test run the right boot slipped on but the left boot would not budge.

There’s a place in Pueblo called Bob Carlino’s Shoe Repair, which I had noticed because it is just up the street from the Pueblo Chieftain. I took the boots there and looked over the photos and other memorabilia on the wall while I waited. Mr. Carlino had repaired piles of boots during his service in World War II and had framed letters of appreciation from the brass. He and his wife placed a stretcher inside the boot and sprayed the leather with a liquid. I came back a couple of hours later and was able to slip the boot on, but barely. They told me to leave the boot on for as long as I could and that it was all they could do. They would not take any payment. I was still wearing those black boots with jeans when I took Francis’ brother Darrell to visitation that evening. I was fine, really, until I went back into the visitation room alone to say goodbye.

———————————–

The funeral morning was sunny and warm. The ceremony was a large Catholic affair with about 200 people in the church. There was a fine tribute by the youngest son Alan, followed by another from granddaughters Sara and Katie. The priest spoke a eulogy, gave the usual scripture readings, and served Communion to the followers. Everyone filed out of the church and we put the casket in the hearse for the ride over to the cemetery.

Since most of the immediate family rode in two funeral home limos, I found myself alone in the procession in our Subaru. I had time to reflect on the past few weeks as the route took us through Pueblo’s East Side, and past some of the town’s major landmarks including the Sangre de Cristo Arts and Conference Center, the Historic Arkansas Riverwalk of Pueblo, the steel mill, and the town’s ethnically diverse Bessemer neighborhood, before we finally arrived at the cemetery on the extreme southwest edge of the city.

It had been a long few weeks, and indeed I would commute from our home in the Wet Mountains to Pueblo eight consecutive days before all was said and done. It had been 10 years since he was diagnosed with cancer, but the last six weeks were the hardest to endure for everyone as he celebrated his last birthday, went into the hospital, and came home to Hospice care. In the end, a good man wrestled with his own mortality and won. Still, for days after he was gone, it would really rip me up when I drove up to the family home and my 3-year-old son Harrison would excitedly say “Gram-pa. Gram-pa.” I was, frankly, exhausted.

———————————–

On Easter Sunday, one week following my father-in-law’s passing, I saw a herd of about 20 deer running like something had spooked them or was chasing them. I stopped and watched. A gray blur was working the contours of the land, paralleling the deer herd. I got out my binoculars and soon found the coyotes. There were three of them.

Hal Walter practices the Three Rs — writing, running and ranching — from his home in the Wet Mountains.