By John Mattingly

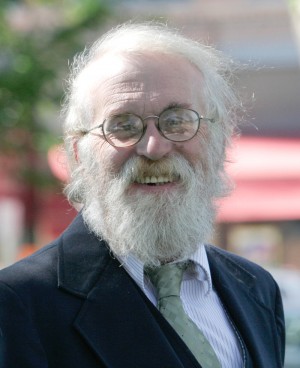

Ed Quillen was a writer’s writer. He not only made a good bit of his living from writing, he cared about other writers.

Anyone who worked with Ed on the “page,” knows he always found a way to be helpful, and kind, even when he knew the written work needed a lot of work. I appreciated his candor, his skill, and … even though it isn’t directly related, it may be ultimately related: his unfailing tolerance for a difficult dog, one named Bodie. Concerning the other, Ed paid a nickel a word when it was hard for a freelancer to net a nickel for a novel.

There’s an expression, the origin of which I have no clue, that says, “The older you get, the more dead people you know.” So the dead live on in the living, in their works, their deeds, and their threads of thought that weave us together as human beings.

For me, Ed’s thoughts and observations will live for a long time, in part because the information age now has the gigabytes to deliver a lot of abrasive content to all of us. I felt Ed was a buffer. He had a way about him, rooted in his command of facts and history, and manifest in his nature, that allowed him to come at the abrasive content from the side, rotate it, tilt it at an unusual angle, and examine it as if it was, perhaps, a curious artifact. This disemboweled the bullshit, and weakened the knees of insistent ideologues. Or, set them off on a very embarrassing rampage.

The information age also has a tendency to turn everything we do into a cliché. Everything a person does these days has already been done, tried, failed, or succeeded, and we hear about it through multi-media. It’s very hard to be original, to find a way to express what hasn’t already been expressed, to see what hasn’t already been seen a million times, or do differently what has been done in every way possible. Even death is a cliché. We all die, and know we will die. Every day we read or hear about death, yet every death manages to escape being a cliché at the moment of passing. When Mike Rosso was good enough to call and tell me, “We lost Ed,” it took my breath away. Every person’s death is unique, and Ed was unique in life.

In his book On Liberty, John Stuart Mills suggested that the best measure of a society is to look at the way the authorities treat eccentrics. Eccentrics, Mills pointed out, expanded the boundaries of “normal” in society, which pushed at the edges, making a little more room at the margin, which allowed more Brownian Motion among the regulars.

Not to say Ed was eccentric. Part Baptist minister, part common sense observer, part wry skeptic, part super geek, and part time-traveling old-timer stuck in a modern world, Ed was usually surprising. Few people are surprising.

Those who are, I cherish without sentimentality.

I knew another Ed, Ed Schnieder, a man who taught me a lot about farming. Like Ed Quillen, he was just Ed, not Edward. The slimness of his name said a lot about him as a man. Ed S. farmed the place north of me. We shared a division box for irrigation water, which is the farming equivalent of being married. When your livelihood depends on water, and you must divide that water fairly with another, you get to know each other like no other.

I never saw Ed S. get dirty, or get excited. He had a calm patience about him, which said he appreciated his chance to be on earth. He always wore clean slacks and some sort of nice shirt, unlike myself who wore raggy blue jeans and a greasy T-shirt. I never figured out how he stayed so tidy while doing field work, mechanical work, and irrigating, but he did. I always seemed to pick up more of the field than he did. One time Ed S. mentioned that I was carrying enough dirt on my jeans to plant a crop. His crops were among the best around, and I was lucky to have a chance to learn from him.

Ed S. had been in World War II, and lost his left leg below the knee at Normandy Beach where he’d seen a lot of men die. Though he limped, it never seemed like a strain, and he never backed away from a shovel. He knew I was a draft dodger from the VietNam war, but he also respected that I was farming. One time he said to me, “This war won’t get you to the short rows.”

“Getting to the short rows” when you’re irrigating is a good thing. It means you’re getting to the end. You’re finishing. It’s the light at the end of the tunnel. I took it from Ed’s remark that the Vietnam War might not get to the short rows. That is: it might never finish right.

Ed S. taught me a lot of little things. “Come spring,” he said to me every spring, “I like to take a set of wrenches and sockets, and go around and tighten all the bolts on all my machinery.”

This proved to be one of the great small wisdoms of the farm. Somehow, machinery has a way of loosening up over the winter, maybe due to freeze-thaw actions. Going through the machines on the farm to check all the nuts and bolts saved me a lot of spring breakdowns, when losing a day could mean losing a crop.

Ed S. also told me, “Put your windrows in a different slot every cutting.”

This was a small trick with long term benefits. If the hay is always put in the same place on each of four cuttings, that slot doesn’t get sun for about a month out of the year, which weakens that part of the field and shortens the life of the stand.

One day Ed S. and I were having trouble with the other farmer on the division box. Ed S. said, “Never pick a fight with a small man who has big feet.”

I’m not sure where this came from, but we worked it out with the man peaceably, though Ed S. had a 10-gauge shotgun bent over his shoulder.

And one of Ed S.’s famous warnings to me: “Don’t drink downstream from the herd.”

This one reminds me of Ed Q., who dependably grazed upstream.

Ed Q. taught me about the Trademark Police, fastidious name and date articulation, and small points of particularity, such as being specific about the sex of a jackass—jack or jenny—when writing about jackasses. To impress me with the importance of specifying “jack” or “jenny” in a story, Ed Q. told me about his jack, who, frustrated by a fussy jenny, fled his pasture and headed for town, where he encountered a fully illuminated white, fiberglass stallion in full buck, outside the Lamplighter Motel. Desperate, the jack attempted to mate with the stallion, provoking speculations as to the hypothetical offspring of such a union. Would it be a half-ass horse, or just a horse’s ass?

To work with Ed was to be often delighted by his criticisms.

And, when Ed Q. said he really liked something, you knew he did.

Both Eds taught me a lot about attention to detail in a way that revealed life’s ultimate bias toward irony.

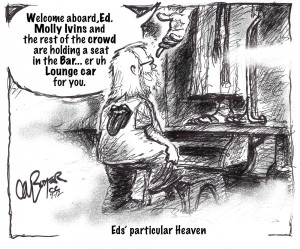

The other night I had dream. I was in a house that I don’t recognize, with a group of people discussing some issue. Ed Quillen sat a table drinking a beer. I sat across from him. He smiled, took a swig, and as he set the bottle down he said, “Well, at least now I can drink a beer and not worry about the damned diabetes.”