By John Mattingly

I look out the window to see my new center pivot on the loose, crossing a road in front of heavy traffic. Cars and trucks are jammed and honking as the machine spreads out like a praying mantis on the warpath, pulling its electric line out of the ground like a giant umbilical cord. It takes out a fence and three power poles, causing flares of flame as the wires arc to ground. The pivot collides with a house and the end tower starts to ascend to the roof.

I wake up in a cold sweat.

Over the forty-two years I’ve farmed, I’ve had some real doozy nightmares. Like the one with my fields of ripe wheat and barley on fire, wild horses and honing jackasses running crazy through leaping flames. Or the earthquake that split my farm in half, leaving a grossly eroded canyon down the middle. Or a deluge that turned my farm into a lake bottom. Or again, a giant cloud of cotton candy falling out of the sky onto my fields, covering everything with a sticky veneer that wouldn’t rub off.

The nightmares usually occur when I’m away from the farm for more than a few days. My wife’s family lives on the East Coast, as do my brothers, so when we go out visit them I can count on several “agrimares,” driven no doubt by the extreme guilt of abandoning my responsibilities, leaving everything to chance, and skipping off to parts unknown like a drunken Judas.

Even after being mostly retired from farming I still have several recurring dreams in the dirt. One I call “the lost field.” During the course of every season, I had many fields, and they became somewhat like children, each field having a personality based on when its ground was ready and in what condition, how well it germinated, and finally, the short but certain legacy of its life from sprout to commodity.

In this recurring dream, I come over a ridge to see a field surrounded by tall trees, a field I’ve totally forgotten about, yet a field that has been my favorite field many times in the past, meaning it’s an especially good field. I can’t understand how I could have failed to plant it. Both surprised and irritated, I run to the field to find it is full of thistles, knapweed, stranglevine and gopher mounds. It looks abandoned, wounded, fallen. I realize I’ve moved all the machinery far away and can’t do anything now.

The field is lost for the season. I pick up a handful of its dirt only to find that the field is no longer dirt. It has turned to ash. In one dream the field had become sponge material, in another chocolate, and still another, white sand. A deeply irritating variation on this dream is one in which I appear at my favorite field to find I’ve failed to irrigate it and the crop is dead.

Another recurring dream involves walking across a field I’ve planted to wheat and seeing beans coming up in the planter rows. The light is ominous, dark red at the horizon. I dig in the unsprouted areas to find wheat seed, but every seed that has sprouted is a bean plant. Then I dig up one of the sprouted beans to find that, indeed, beans are sprouting from wheat seed. This is very, very disturbing, and even after I wake up I feel cross-threaded with reality for the rest of the day. With all the uncertainties of farming, the one thing a farmer can depend on is seeds. Plant wheat seeds, and wheat plants come up, plant beans, beans come up. “As ye sow, so shall ye reap.” Few processes are more basic, few processes more dependable. So when beans sprout from wheat seed, the world is probably nearing The End, or we’re being side-swiped by a parallel universe.

But enough with the nightmares. There are also lots of pleasant farmer dreams, and if I may say so in this publication without fear of censorship or over-sharing, dreams with some sexual suggestiveness. Delicately penetrating mother earth after the foreplay of massaging a seedbed from her coarse skin is very much an act of love. I’ve noted that this particular kind of dream has become less frequent as the mechanization of farming increased.

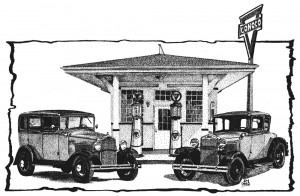

Back in 1968, when I bought my first 80 acres after the big sugar beet freeze in Larimer County, all my tractors were open air with a metal seat. One tractor had a weatherproof radio mounted on the fender, antenna wagging in the air like a rat’s tail, so I could occasionally listen to music or news or a ball game over the droning of the engine and squeaks of whatever tool the tractor had engaged. At the end of the day I was covered in dust, ears ringing, eyes watering, hands tingling, hemorrhoids howling. There was definitely a greater direct contact with the ground with the old machines, and thus the sensations of interaction, or to be consistent with the metaphor, intercourse, with the earth was more pronounced.

As time rose on I purchased tractors with cabs, air conditioning and heater, and eventually air-cushioned action seats and high-end stereo systems that made the actual work of farming more like watching a movie of farming than actually doing it. Wonderful as these machines were, they created detachment between farmer and ground and as this progression advanced, my earthy dreams of working the ground tended to decrease.

Dreams of the earthly/sexual variety were always vague, mostly without plot, simply stirring up a sensation of connection with the ground that felt like the bond with a loved one. My father told me the most important thing on the farm was my footprints. This obtained from a kind of hubris common to his generation, a notion that humans were in total control and thus had to be on the spot for anything important, or of value, to happen. The farmer in this mind set made things happen; he didn’t wait for them to happen. I rotated this wisdom a few degrees, as any son would do, allowing that total control really wasn’t possible, and the slippage in that tolerance yielded much in simple observation, appreciation, and yes, love of the ground that I believe manifest in these type of dreams. Sometimes they presented with a bright, glowing orb of white or red that I held in my hand, or that hovered over a soft, inviting field.

Of course, there are also dreams of endless bounty, of a crop that is quite literally a braggart’s dream – bales so thick in the field that it’s impossible to drive through them, wheat or barley or canola with grain heads nearly as large as utensils, drooping to the ground. I had several dreams of grain bins overflowing. Just the other night I dreamed of hovering over two circles of perfect wheat coming ripe, heads filling all six rows, solid green in strong stems, and the center pivots going around, delivering a nice half-inch rainstorm. I awoke to a day that passed with perfect peace.

John Mattingly cultivates prose, among other things, and was most recently seen near Creede.