By George Sibley

“In the hope you don’t produce too much civilization in the Gunnison Country.” – Inscription in “Deep in the Heart of the Rockies”

No one had thought this would happen so soon – the challenge of how to remember Ed Quillen. When I think about Quillen, I’m always thinking ahead to something – how best to fit a Quillen diatribe into the next Headwaters conference at Western State, whether there was time on the upcoming trip to Denver to stop in Salida for a cup of coffee, wondering what next Sunday’s column would be about, writing him an email about this Sunday’s column.

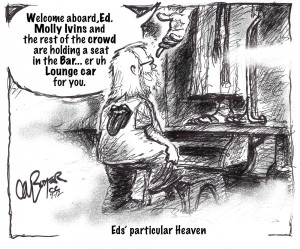

My first fumbling stab at remembering him came as the news of his sudden passing spread through the grapevine Sunday, June 3; I passed the sad news along to people I knew who also knew Quillen with the lead, “We have lost a great curmudgeon.” But that already slips toward an inexcusable in Quillen’s universe, sentimentality – even though Quillen used the C-word about himself. When Quillen said it about himself, it was usually to let you down a little more gently as the air leaked out of the balloon he’d just terminally pricked – “But then I’m just an old curmudgeon.” His disguise, but not his epitaph.

So how to remember Quillen? Writer, historian, thinker, master of the 800-word essay, polymath, father-husband-dog lover-homebody, small-town cosmopolitan. The sum of the parts remains just the sum of the parts, and that which was larger than the sum of the parts is now just gone.

One of my more enduring memories of Quillen is working together on the “discovery” and official naming of Headwaters Hill. This is a non-descript little bump on the Continental Divide that just happens, for this moment in geological time, to shed water into all three of the great rivers that rise in “Central Colorado.” Silver Creek drops down into the Arkansas River, Marshall Creek down to the Gunnison and ultimately the Colorado River, and Middle Creek to the “Closed Basin” that the Bureau of Reclamation has joined to the Rio Grande (an obviously rational completion of something God didn’t quite finish). We hiked to Headwaters Hill with a pack of Western State College students back when Quillen was still smoking a lot, and I remember looking back about a hundred yards into the hike, and seeing Quillen head down, hands on knees, and thinking “uh oh.” But I guess he was just downshifting into granny gear; he found his second wind and made it all nine miles to the hill and back.

He wrote about what we were calling Headwaters Hill in a column, and that led to a connection with Dale Sanderson, a cartographer in Denver who had also discovered the uniqueness of Headwaters Hill on his own. Sanderson actually knew how to get things officially named, and led us through the process of putting the idea before the Geological Survey’s “Board of Geographic Names.” They accepted the name, and it has begun to show up on maps.

That is not a big thing, in terms of “the march of history” – but in the amble, slog, and wander of history, it is an interesting thing – a single source for tributaries of three great rivers rising in Colorado, “a land where life is written in water,” according to another Colorado poet whom I would call somewhat Quillenesque, Thomas Hornsby Ferril. Or maybe Quillen was somewhat Ferrilean. Two men who literally, and literarily, loved everything about Colorado and the mountain West.

Was Quillen a poet? Not in the way in which we conventionally parse literary output – although anyone who can actually say something intelligent in a 700-800 word essay understands the poet’s discipline. But “poet” used to be used in a larger “bardic” sense – as in this, from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay on The Poet: “The ancient British bards had for the title of their order, ‘Those who are free throughout the world.’ They are free and they make free.” That’s close enough to Quillen for me.

The world seems content to deposit him in the “liberal” box, mostly because he tends to unleash the laser of his wit most frequently on what passes today for conservatives. I think there were two reasons for that: first, because they have been in charge for the last three-plus decades, and it is the bardic poet’s nature not to be a running dog with “The Committee that really runs America” or anything else. But second – he began his political life as a Republican and has said that he “believes in most of the things that Republicans used to say they believed in – small and limited government, individual responsibility, families and that sort of thing.” His jibes and slaps at Republicans are those of a jilted lover – he cited Ronald Reagan’s reason for switching the other way: “I didn’t leave the party; the party left me.”

But unlike Reagan, he didn’t switch all the way to the other side. Were it still the 1930s or 40s, he might have become a good voice for working-class Democrats – Leadville Democrats. But he had no more love for today’s “Boulder Democrats” than he had for Republicans.

At the Headwaters conferences at Western State College, I often gave Quillen the assignment of summarizing a session – probably revealing a latent masochism. But since the Headwaters conferences tended to be primarily liberal progressives talking to each other because the invited conservative speakers almost always left as soon as they finished speaking, brooking no discussion, I’d get Quillen to beat up on us a little – liberals need that every now and then. He would seize with gusto the opportunity to pop most of the liberal and progressive balloons that had been floated there, all in that wry way he had of making things sound funny that really weren’t, and we would all be howling with laughter at ourselves. This was the liberal alternative to charging the stage howling and lynching him. It was healthy, like a good laxative can be healthy.

So neither liberal nor conservative in any conventional sense. He wrote frequently for High Country News – including one of the best things that ever came out of that journal, a long, deeply-researched essay about the metropolizing of the West, under the working title, “Is Denver necessary?” But he was not an environmentalist either – “I’m not big on purity,” he said in a column. He talked – well, a bit sentimentally maybe – about “old beater pickups” and those who drove them (perhaps with some uncontrolled substance under the seat), and he recommended putting old refrigerators and washers on the porch to discourage yuppies from moving in and ruining the neighborhood. But, he was neither redneck nor hippie – he read too much, thought too much. (Is anyone else wondering exactly what he was reading in his favorite chair when he died?)

I have wasted some time this past week, trying to figure out the answer to the question I always thought there would be time to ask someday: “Well, Ed, dammit, what is your vision for America then?” It would have been an afternoon at the Vic or an evening at the Cattleman’s in Gunnison (long gone now). What measures up, Ed? What’s good enough for your America?

Now that Ed is gone, we can all collage our own answers to that and other questions from the two-million-plus words he left behind. Deep in the Heart of the Rockies is back in my bathroom, for those mostly quiet and contemplative parts of the day.

Myself, I think what Quillen was, still is in those pages, is a small-r republican. A Jeffersonian: he wanted to live in an intelligent community that knew its place (in all senses of the phrase), knew its earthly limits, didn’t measure all its riches in dollars, had a government neither big nor small just good, a populace that daily walked their dogs through it all to keep it fresh in the mind and deep in the heart.

And I realize, of course, that I am just giving my answer to the question that I never got around to putting to Quillen, and now never can. That is what we miss most when someone leaves us: that conversation is over.

So now we move on, each of us with a pocket version of Quillen, quotations from Chairman Ed, and what we probably all ought to do is just go do our version of his daily walk with his dog Bodie. Here is an epitaph for Ed, from an earlier bardic poet, his spiritual brother Walt Whitman:

I depart as air, I shake my white locks at the runaway sun,

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fibre your blood.

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.

– From “Song of Myself”