By George Sibley

“Home is where one starts from.” – T.S. Eliot

When the publisher of this journal suggested we contributing authors contemplate the topic of “home” for the new year’s first issue, it got the brain to firing on most of its cylinders. Partly because this is frequent topic of conversation between my partner and me. At home, as it were, which is most basically wherever we are at the end of the afternoon when we can sit down together with a beer, a bowl of popcorn, and (in season) a fire.

But when we’re “at home” on that basic level, my partner and I find ourselves talking about home on another level, home as a place, and there we are not in agreement. The place where we live here in Central Colorado is home for me, but not for her. So – because “sense of place” gets talked about a lot these days – we explore that concept of home-as-place pretty often.

Her home of the heart is in Wisconsin, which is where she was born, and lived through her high school years. She has not actually lived there since her college summers; she has in fact lived in Colorado about twice as long as she lived in Wisconsin. But Wisconsin is still “home” to her. She doesn’t dislike Colorado, and has created a rich life here. But it isn’t “home,” and since we both began to retire a few years ago, we have been going to Wisconsin for a month every year – not to visit her family, which is now all gone too, one way or another, but just to be in Wisconsin.

I think her experience of the home place is probably shared by many people, maybe most people – suggesting that home is not so much our choice as a choice made for us by the fact of being born there. For most of the natural history of our species, that was probably the way it was for everyone: you lived and eventually died near where you were born. We have been blessed – I guess – with the choice to go about anywhere we want. A a lot of us, maybe most of us, find ourselves (like my partner) living most of our lives somewhere other than “where we started from,” as the poet put it.

But for some of us, that “somewhere other” actually becomes home, in a way our birth place isn’t. That’s been my experience, anyway. I was born in Western Pennsylvania, up the Allegheny River north of Pittsburgh, lived there through the growing-up years, and went to college in Pittsburgh. The Allegheny Basin is a beautiful place with a rich history, and I thought of it as home until I had been away for a couple of years, in Colorado in the Army. A sad episode that is another story entirely, but when it ended I returned to Western Pennsylvania, thinking I was going home, only to realize – after a brief episode of being mostly lost driving a taxicab in Pittsburgh (not a romantic lostness at all, just plain lost) – that what I really wanted to do was go back to Colorado.

A factor in my situation might be the fact that, in a biological sense, Colorado really was “where I started from.” My mother lugged me in utero from Denver to Western Pennsylvania when my father got a job offer he couldn’t refuse. My parents were both Colorado natives, somewhat displaced in Pennsylvania. While I never thought to ask either of them, I think they would both have said their heart’s home was Colorado. They both still had family in the Denver area, and we visited Colorado several times when I was a kid.

After the People’s Cab Company put me out of our mutual misery, I left Western Pennsylvania for good and returned to Colorado – but this time to the mountains, the true Colorado. Going to Colorado and ending up on the Front Range is like wanting to go to sea and ending up in San Francisco.

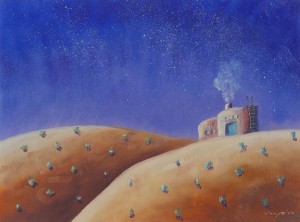

At that point, I wasn’t even looking for a home; I was just wandering seasonally from job to job, and enjoying that, sort of. But that led me to the Upper Gunnison River valley one winter, and there I was. I didn’t realize I had found a home until I left it for a summer construction job elsewhere and realized I missed the place. I went back for another winter, and never really left again (although I have been away from time to time).

Home centered at first around the Upper Gunnison town of Crested Butte in the mid-1960s – and the time was important. I would probably have felt differently about that town had I arrived in the late 1980s or early 90s. This leads me to suspect that home might be as a much associated with a particular time as a particular place. In the mid-60s Crested Butte was just a little end-of-the-road town between destinies. A former coal-mining town that, in 1966, had a struggling hardrock mine on one mountain and a struggling ski area on another mountain, and in the valley between lay the town from where we all went to work every day to one mountain or the other, and returned at night to drink beer together, talk, argue, fight, hook up, etc.

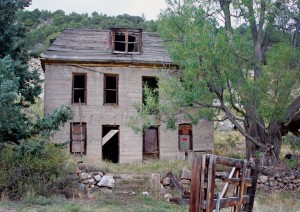

I get a little stuck when I try to figure out what made Crested Butte – or more accurately maybe, the headwaters end of the Upper Gunnison valley – feel like the home I didn’t even realize I’d been looking for. It sounds suspect to say this, but some of its appeal undoubtedly lay in the fact that it seemed to be about as far away from the American mainstream as I could get without giving up running water and electricity.

The people there in that little town were part of that feeling. Some of them were people like me – semi-bohemian refugees from the American mainstream and our own epiphytic bourgeoisie roots, drawn there by the potential for reinvention the mountains seemed to promise. The rest of the people there, the real substance of the community, were left over from the town’s coal-mining days, most of them first- or second-generation Euro-Americans retreating ahead of the political and economic chaos of central and southern Europe. Some of them were old coalminers still there because, thanks to John L. Lewis and their own courage in following him, they’d been able to retire. Some of them because they’d invested in a business and couldn’t afford to leave. Still others because there was always the chance that the ASARCO skeleton shifts would find the vein again in Mt. Emmons and their old friends scattered by the town’s economic diaspora would all be able to come back, and the town would thrive again. In the meantime, they were glad enough to see us, or anyone. They didn’t see the ski area as the foundation for a real economy (“gotta have the lunch bucket”), but it was better than nothing to help get through the long mountain winter.

Altogether, the valley was, or seemed to be, a long way from the increasingly imperial America I was in retreat from, it seemed, if anything, like a place where America hadn’t yet happened. And that, to the perfervid mind of an over-educated and under-experienced liberal arts graduate, meant it was a place where we might make America happen the right way. Whatever that was.

It was a place where one could feel like one could make a difference. Up to that point, my life had changed from being a good hoop-jumping lad trying to figure out how to fit into some niche in the imperial American juggernaut rolling over the world, to realizing all I really wanted to do was to figure out how to both stay off of, and out of the way of, that juggernaut. But there, at the end of the road in the Colorado mountains in the mid-1960s, with a bunch of fellow survivors, it felt like there were as many destinies as there were mountains on the horizons. The time and place for the soul that has found its home.

I realize that there was a fair amount of self-delusion associated with that feeling. I didn’t understand then how deeply the juggernaut already had its extensions of pipes and wires and trucks and banks embedded in the valley, and now even more so. But it’s still rough country for juggernauts with only modest returns, and down valley breezes still carry a whiff of that feeling that something other is possible, and that keeps me here.

Was it something the same for my partner in her Wisconsin home – not just a matter of birthplace, but a “starting place” in a deeper way? She spent her high school and college summers – those same 1960s – following her father all over Wisconsin in his university job helping people in Wisconsin towns tell the stories of the lives of their communities. A rich, deep exposure in trying to jump-start another non-imperial America, work worth carrying beyond home to other places and times, which she continues to do.

So – home? I would simplify Eliot’s line by one word, “Home is where one starts.” The confluence of time and place at which one wakes up and begins to dream toward better times and places, as one is able to.

George Sibley is a writer who still feels at home in Central Colorado despite mostly just “lifting his eyes unto the hills” rather than hauling his butt up them too.