By Peter Anderson

The vultures are leaving their roost over by the creek. They follow the Rio Grande south until the climate suits them. The sandhill cranes are flying in from the north, sometimes barely visible in the high skies as they circle, gather themselves and get their bearings; sometimes their weird cackling call precedes them as they emerge from low-slung autumn clouds. Elk are bugling for mates, bears are scavenging for extra calories before the big sleep, and coyotes are on the prowl for unsuspecting house pets. Here at the end of the road, summer drifters who came to town with little more than a sleeping bag are dreaming of sunshine and saguaros or maybe some seaside town in southern California, hoping to set aside some cash for the road. This is a restless time.

I am thinking about restlessness tonight in all its varied forms, realizing that I am not as prone to it as I once was. I no longer live west of a river town after the water has gone out of the canyon and most of my guiding buddies have gone with it. I no longer work a rangering job in the High Uintas, hoping for winter work in Salt Lake City, as I pack out my seasonal camp and the snow line comes down behind me. I no longer pull out the road atlas and spend hours dreaming about distant college towns when life feels a little flat. Chalk it up to age, steadier work, a family; it’s easier to stay in one place than it used to be.

Nevertheless, the universe itself is a restless place. Galaxies are moving away from one another. The stars that we see in the Milky Way are farther away today than they were yesterday. Why should human beings, dust motes born of the same carbon, be any less restless? Nothing stays the same. Everything’s moving.

Small mountain towns are finite social constellations. Economies rise and fall, and with them, populations. Back in the early 1980s, I witnessed the effects of Climax Molybdenum Mine shutting down. Many main street storefronts, from Leadville down to Salida, were boarded up and stayed that way long enough for many people to move on. Since then, I’ve lived in communities like Moab, Utah that rode the wave of a post-mining new-west boom. Goodbye uranium. Hello mountain bikes. Either trajectory, whether boom or bust, can leave one feeling as though something good and familiar is slipping away.

Fortunately, I have yet to experience either boom or bust here in Crestone. Still, people come and go fairly regularly. Many of the friends we’ve made over the years have moved on. There’s nothing wrong with that. This is a hard place to live. Big dreams dwindle along with bank accounts. Big winds take their toll, as do long winters, isolation, and clouds of mosquitoes. But it’s still hard for me to hear my nine year-old daughter talking about friends who have moved to bigger towns and bigger schools and how much she misses them. Sometimes I wish, for her sake and mine, that our town had a more stable population.

But migrations circle back on themselves. The vultures and the sandhills will be back in the spring, right about the time the bears are waking up. And come fall, with a little good fortune, we will have made another trip around the sun, and maybe a few more ten-year-olds will have found their way to a little school at the end of the road.

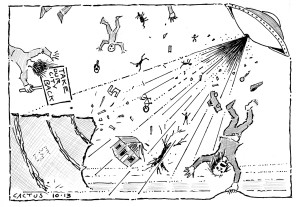

A restless time in an already restless town. It’s restless here in part because many people drawn to this place have been wanderers, myself included; travelers, if their restlessness included an itinerary; or seekers, if they chose a road whose only real map resides somewhere in their soul.

It’s also easy to get restless here because it’s a difficult place to live. Jobs are scarce. Big dreams often don’t pan out. The wind blows hard. And it’s a long way from here to anywhere else.