Article by Lynda La Rocca

Local Artists – August 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

ARTIST SAUL STEINBERG, known for his cover illustrations for the New Yorker magazine, once described doodling as “the brooding of the mind.”

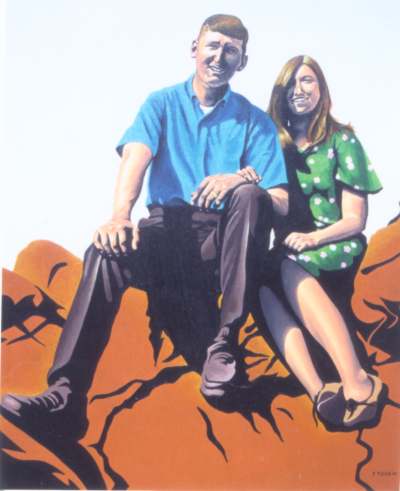

But for Salida artist Steve Flynn, doodling was the springboard for a style that integrates a variety of media with a wide range of subject matter to produce finely detailed work that runs the gamut from playful and whimsical to grippingly realistic.

As a child, Flynn doodled constantly, using a ballpoint pen to fill his school notebooks with abstract designs, shading, and crosshatching, even drawing on his blue jeans when he ran out of notebook space.

“In school, you doodle,” says Flynn, 33. “But I was ‘doodle-plus.’ I was a good student, I listened and did well in my classes, but I was constantly drawing.”

By sixth grade, Flynn’s obsessive scribbling had caught the attention of a high school art teacher in his hometown of Tupper Lake, New York. This teacher became a mentor, pushing the youngster to attempt lifelike depictions of subjects such as dandelions and individual blades of grass. Meanwhile, Flynn and his mother Michele, a retired teacher, made frequent trips to New York City, where he was exposed to world-class works at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Museum of Modern Art.

With two years left in high school, Flynn had already satisfied graduation requirements for mathematics and science and wanted to take additional art courses.

“The principal called my mom and said, ‘But how can he become an engineer without math and science?'” Flynn recalls. “My mother said, ‘He doesn’t want to be an engineer; he wants to be an artist, so why can’t he take art?’ This was a small town and it was hard for some people to believe that anyone would actually want to study art. But my mom convinced them, and I got my extra art classes.”

In college, Flynn experimented with media ranging from pen and ink and colored pencils to wood and video. He also mixed ordinary soil with acrylic polymer, an unusual leaning still evident today in his use of soil to create striking, naturalistic borders or “frames” for some of his work. And he developed an ongoing passion for photography.

“The big thing for me then was mixing media. It still is, actually,” says Flynn, who currently works in graphite, ink, acrylics, oils, watercolors, charcoal, and chalk pastels, and also produces black-and-white and color photographic prints.

AFTER EARNING an associate’s degree in commercial illustration from New York’s Cazenovia College and a bachelor’s degree in fine arts in sculpture from the State University of New York’s Purchase College, Flynn landed in Colorado.

“I had been rejecting business, and I realized that I needed to look more seriously at the business aspect of art,” Flynn says. So he started creating logos and painting signs for commercial enterprises.

“But I kept asking myself, ‘What’s important to me now? What subject do I really want to paint?’ And the answer was, ‘My animals, my family.'”

Flynn and his wife Barbara, a beadwork artist and painter, were — and still are — the “parents” of two dogs and a cat. So Flynn began using them as subjects in his work. “That’s where the emotion, the connection was.”

In 1999, after Flynn showed his pet portraits at Poor Richard’s restaurant in Colorado Springs, people began commissioning him to do paintings of their own pets.

Often, Flynn never actually saw the subjects of his animal art. “I’d interview [the pet owners], listen to their story, ask about their favorite colors, their pet’s personality, and get a feel for the person and the pet and their relationship,” he explains.

Then, using borrowed photographs that best captured the pet’s individuality, Flynn would go to work. The result was a series of boldly colored, high-contrast portrayals of cats majestically surveying their domain and dogs dream ing of juicy bones or canine pals. In this series, it’s the eyes that most immediately illustrate Flynn’s sensitivity to, and affection for, his subjects. Whether alert, tranquil, startled, eager, or sometimes literally reflecting the pet’s view of the world, the eyes in Flynn’s animal portraits positively glow with mesmerizing intensity.

FLYNN’S PENCHANT for using lots of black, mixed with blues to produce a cold hue or with reds or yellows for a warmer tone, is an idea borrowed from 17th century Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn, whose work has been a major influence on Flynn’s own.

“Rembrandt said he never painted with true black. I’m that way, too,” he explains. “Rembrandt’s sense of light and darkness really had an impact on me, as did his outlook on life. Even when the bottom fell out for Rembrandt and he was dirt poor — which I can relate to, I’ve been there, too — he kept painting. That’s very inspirational to me.”

Other artistic influences include the French and Spanish masters Manet, Matisse, El Greco, Velàzquez, Goya, and Picasso.

“I look at [the work of] artists I like, and I learn about myself through what attracts me to them,” Flynn says.

In addition to Poor Richard’s, Flynn, who moved to Salida in 1999, has shown his work at Gertrude’s Restaurant in Colorado Springs, Bongo Billy’s Salida Café, the Salida Steamplant, and currently at Moose Mountain Studio on West First Street in Salida.

And last year, Flynn began pursuing yet another path when he signed on as cellar assistant at Salida’s own Mountain Spirit Winery, Ltd.

“This job blends well with my art and with me as a person,” Flynn explains. “There’s an important connection between art and wine, and that’s craftsmanship. Fine craftsmanship in wine means having the best ingredients, using them well, and creating your product with care. And now I’m working with people (owners and winemakers Michael and Terry Barkett and cellar manager Karl Hinther) who do everything with great care and produce a quality product that’s crafted by hand — just the way art is crafted by hand.”

“I am a craftsman, no matter what I do,” he adds. “And I’m always going to create, no matter what my circumstances are.”

And Flynn intends to do his creating right here in Central Colorado, a region that draws him with its spectacular scenery and vast open spaces.

“There’s a term in winemaking called ‘terroir,'” he says. (Author’s note: “Terroir” generally refers to a certain quality in wine deriving from the physical environment — i.e., soil type, microclimate — of a specific vine yard.) “And that’s what I’m experiencing here. I’m going to get the best work, the best play out of myself here because the people, the atmosphere, the surroundings, all bring out the best in me. You have to cultivate that in yourself, just as carefully as you cultivate grapes.”

As for the future, Flynn will be content as long as he keeps producing, learning, and growing artistically.

“I’m not trying to achieve anything in terms of a specific influence,” he says. “What’s important to me is sharing. It’s like poetry — the circle’s not complete until you read it. With visual art, the circle isn’t complete until you show it.

“My goal is just to create art,” Flynn adds. “If you create straight from your heart, from your soul, there will always be an audience for your work. I want to use my talents to enrich my life and then, when I share them with people, hopefully, their lives will be enriched, too.”

Lynda La Rocca sometimes teaches in Leadville or shares poetry in Salida, but generally she lives and writes in Twin Lakes.