Note: The following is an excerpt from the book, Colorado Then & Now by Grant Collier and his grandfather Joseph Collier.

“This mountain was named after the miners, after D. C. Collier, one of the editors and proprietors of the Register, in consideration of his eminent success as a prospector. The view is from the Perue Fork of the Snake River, which runs down through the willows in the foreground. It is from the direct front, looking down through one of the beautiful, sunny, grassy, parks, which constantly recur, and which, in their season, are covered with gorgeous foliage so peculiar to the western slope of the continent.” – Joseph Collier on an image of Collier Mountain

Of all the gold and silver rushes in Colorado, none compared to the one that occurred in Leadville in 1878. The vast deposits of silver helped build the fortunes of now-legendary men like Horace Tabor, David May and Meyer Guggenheim.

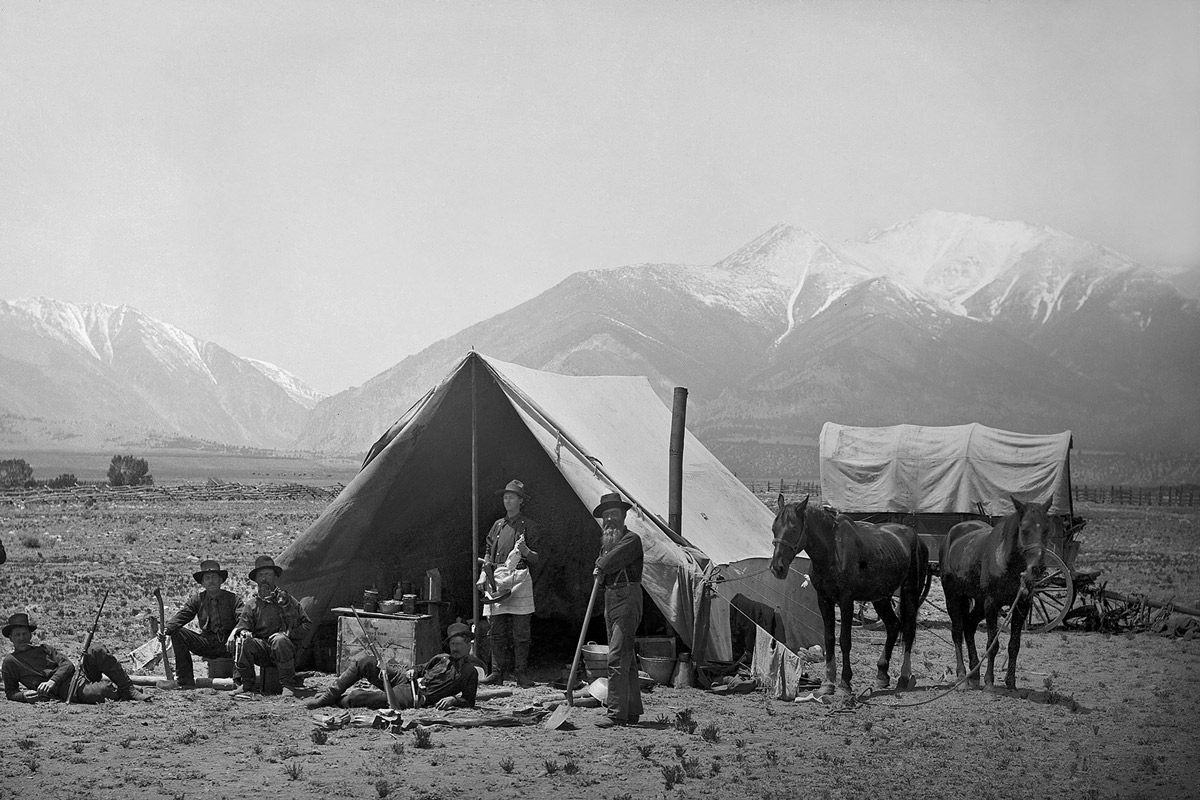

Although most fortunes in Leadville were made from silver, the first discovery in the area was of gold. Abe Lee found deposits of this mineral in California Gulch in 1860. Within a year, nearly 10,000 prospectors converged on the area, and the town of Oro City was established.

Although large amounts of gold were discovered, heavy black sand clogged the prospectors’ sluice boxes, making it very difficult to separate the gold from the sand. As a result, miners left Oro City nearly as quickly as they had arrived. For the next decade, the region was largely abandoned, as miners searched for riches in other parts of the state.

In 1874, silver was discovered in California Gulch and some new mines were staked. The real rush to Leadville, however, did not begin until 1878, when George Fryer discovered a rich vein of silver on what became known as Fryer’s Hill. By the following year, the population of Leadville had soared to 18,000, and by 1880 it was up to 40,000. The huge influx of residents outpaced housing construction, and people were forced to sleep in tents, street alleys or on the floors of saloons and other businesses.

Since Leadville is nearly two miles above sea level, it was not a good place to be homeless. Hundreds are said to have died due to the freezing temperatures and the poor living conditions. Others died from the violence that often erupted in this boisterous mining town. In 1879 Leadville had just four banks and four churches, but boasted over 200 saloons and gambling houses and at least six brothels.

One patron of these establishments was the infamous gambler and gunfighter Doc Holliday, who moved to Leadville in 1883. As was the case throughout his life, Holliday could not stay out of trouble in Leadville. In 1884, he is said to have shot Billy Allen in the arm in Hyman’s Saloon. Holliday was put on trial, but the town’s residents didn’t seem to care for Billy Allen and Holliday was acquitted.

Despite the early chaos, men continued to arrive in Leadville by the thousands due to stories of those who struck it rich overnight. The most famous such story was that of Horace Tabor, who made his initial fortune on the Little Pittsburgh Mine. Tabor later purchased the Matchless Mine, which became one of the region’s largest producers.

For a while, it seemed as though Tabor could do no wrong. A man referred to as “Chicken Bill” Lovell salted the Chrysolite mining claim using silver ore from Horace Tabor’s Little Pittsburgh mine. He then sold the claim to Tabor, who soon realized he had been swindled. Tabor, however, refused to give up on this claim and eventually found a vein of silver worth millions of dollars.

While some made their fortunes directly off of silver mines, others benefited more indirectly from the discoveries. David May opened a dry goods store, which went on to become a national chain called The May Department Stores Company. Also, Meyer Guggenheim built much of his huge family fortune smelting ore from the mines.

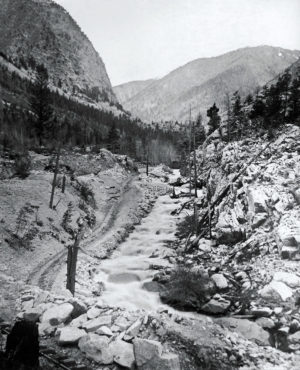

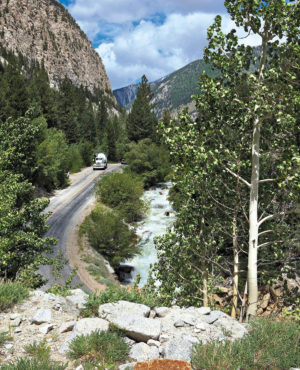

As Leadville continued to grow, some prospectors sought out claims in less-populated areas. Some of the most promising finds were made near the towns of St. Elmo and Pitkin. These two communities were located just ten miles apart, but they were separated by immense mountain peaks. The Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad decided to connect the towns by boring the first railroad tunnel under the Continental Divide. This engineering marvel was completed in 1882, and at the time it was the most expensive tunnel ever built.

[InContentAdTwo] The tunnel would prove to be a financial disaster for the company. Some of the richest veins of ore in the neighboring mines became depleted, and many prospectors departed the area. Also, snowslides frequently came roaring down the mountains, and the tracks often had to be closed during winter. One particularly devastating slide completely destroyed the town of Woodstock and killed 13 people. By 1910 the cost of maintaining the tunnel had become impractical, and it was permanently closed.

While towns like St. Elmo and Pitkin never came close to rivaling Leadville, one town did. This town was originally named Ute City, but its name was changed to Aspen in 1880. During its peak years in 1891 and 1892, Aspen surpassed Leadville as the nation’s most productive silver mining town. This prosperity, however, was short-lived, as nearly every town in the region was devastated by the collapse of silver prices following the repeal of the Sherman Act in 1893. Thousands of residents departed, and many of the mines were closed.

One of the hardest hit during this time was Horace Tabor, who lost nearly everything he owned. While on his deathbed in 1899, he reportedly told his second wife, Baby Doe, to hang onto the Matchless Mine, as he was convinced it would be worth millions when silver prices recovered. Baby Doe took his advice to heart, and she eventually took up residence in a small, abandoned cabin at the mine site. In 1935 her body, dressed in rags, was found frozen to the cabin floor.

Mining picked up again near Leadville when the Climax Molybdenum Mine opened in 1915. At one point, this mine produced three-fourths of the world’s molybdenum. Although the mine was shut down for many years, it reopened in 2012 and continues to operate today. The scars on the landscape from this mining operation are tremendous. An entire mountainside has been dug out and massive amounts of tailings have been deposited in the valley floor. These tailings have entirely buried the former townsites of Kokomo, Robertson and Recen.

Despite the reopening of the Climax mine, Leadville’s economy today depends primarily on tourists who visit in the summer. Many of these tourists come to see the mining museums in town. Inside, they can briefly be transported back to a time when the hopes and dreams of thousands of people lay buried in the hillsides above Leadville. Although a few lucky men did realize their dreams, the hopes of others were all too often dashed by the cold reality of surviving in this raucous town in the unforgiving Rocky Mountains.

Colorado Then & Now can be purchased in bookstores or by visiting www.CollierPublishing.com