Article by Steve Voynick

Mining – July 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

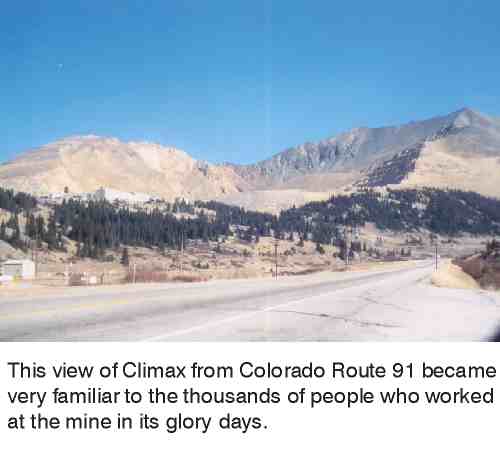

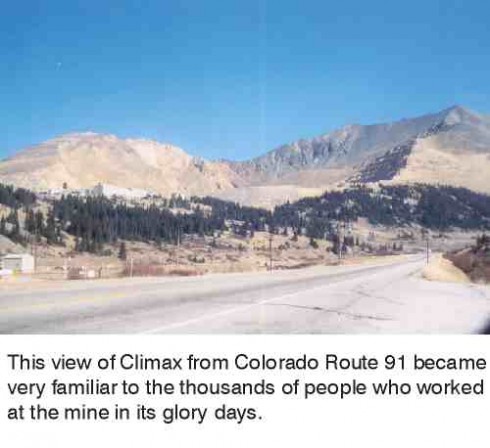

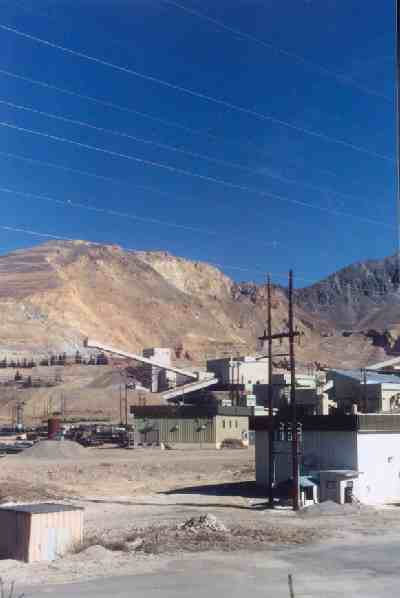

ON FEBRUARY 16, 2004, it seemed that the off-and-on-again rumors of the past 20 years had finally come true. The headline of a front-page, above-the-fold article in The Denver Post announced “Leadville Taps Vein of Hope.” An accompanying color photo showed a cluster of earth-colored mill buildings set against snow-covered, open-pit benches on the side of Ceresco Ridge — a signature image of the Climax Mine. More than a few folks probably glanced at that headline and thought of skipping work at Copper Mountain or Vail to rush up to the mine on Monday morning to fill out employment applications.

But, alas, it was only a slow news day at the Post, for the headline article was, as it turned out, really non-news. Further reading quickly dashed any hopes that Climax was about to rise from its own ashes. A sub-headline in much smaller print announced, “Firm says town’s dream of reopened mine to come true — eventually.” The key word, as the text of the article would reveal, was “eventually.”

A drive to Frémont Pass and the Climax Mine sometimes seems like a journey back through time. Flags flutter high over the main gate, the mill buildings are in good shape, and the open-pit benches on Ceresco Ridge look like they were mined just yesterday. In fact, the mine today appears much as it did on any Sunday in 1980, a day when it was idle, but also when 3,000 employees on three shifts would show up the next day to mine and mill more molybdenite ore.

But Climax shifts these days have only 17 full-time, year-round employees, and perhaps three times that number when extra contract personnel are hired during the summer construction season. Most activity on the sprawling mine site, at least during the winter months, takes place in the first-floor offices of the big mill building just up the hill from the front gate. Yet despite the small number of employees, visitors to the Climax offices sense an almost tangible urgency that reflects tight schedules and lots of work waiting to be done.

Jay Cupp manages the Climax Mine. He’s the most recent of 26 individuals to do so over the past 87 years. Cupp arrived at Climax in 1995 to direct a brief resumption of mining in the open pit. But there has been no mining since, and his current responsibilities are unlike those of any of his predecessors.

“Today at Climax we have two main jobs — caring for the environment and maintaining the facilities to be ready for an eventual resumption of mining,” Cupp explains. “Obviously we’re not mining now, so our primary concern is the environment. That means treating water and reclamation — and that’s more than enough to keep us busy.”

But “busy” is no longer a word that most casual observers associate with the Climax Mine. Twenty-three years have passed since the mine last operated at capacity, and details about the layoffs and shutdowns are already fading into history. Today, a lot of folks think of the mine as simply having been “closed” for the past two decades. And that’s how books, magazines, and newspapers often describe the mine — simply as “closed for the past 20 years.”

“The Climax Mine has never been ‘closed,'” Cupp points out emphatically. “Sure, production has been suspended at various times, as it is now. But we have many responsibilities to meet that are not related to production. So even though we are not mining and milling, we’re far from closed.”

TO UNDERSTAND the current status and direction of the mine requires a closer look at the past two decades. In a nutshell, Climax fell from grace as one of the nation’s biggest mines after radical shifts in molybdenum supply and demand sent molybdenum prices soaring, then crashing. The mine first reduced production in October 1981. Then in January 1982, it laid off 600 employees and cut production in half. By that September, the mine had suspended operations in a shutdown that would last 20 months.

But that’s only the beginning of the story. Climax reopened in April 1984, working at 40 percent of capacity with 700 employees. But by 1987, after operations had been cut back to underground “clean-up” production at just 12 percent of capacity, the mine went into “hard shutdown” for the first time. Underground clean-up operations resumed in 1989 with just 165 employees and lasted two years. The open pit produced briefly in 1992, then went into hard shutdown again.

Although it might not seem that way, the Climax Mine had actually operated at reduced production levels for seven of the ten years that followed the initial layoffs. During this time, Climax was still part of AMAX Minerals, a corporation formed by the 1958 merger of American Metals Climax, Inc., and the original Climax Molybdenum Company. In the 1980s, when AMAX was faltering on the brink of collapse and wide-open for a takeover, it was still very molybdenum-oriented and saw only one direction for the Climax Mine — more mining. AMAX tried desperately to make Climax a “swing producer,” a mine that could be quickly reactivated or mothballed as molybdenum-market conditions dictated.

That thinking changed in 1993, when the Cyprus Minerals Company merged with (read “bought out”) AMAX to form the Cyprus-AMAX Minerals Company. Over the next ten years, the Climax Mine would operate only once, briefly in 1995.

Another ownership change came in 1999, when Phoenix-based Phelps Dodge Corporation acquired Cyprus-AMAX Minerals. Today, the Climax Mine is a unit of the Climax Molybdenum Company, a wholly owned Phelps Dodge subsidiary.

LOOKING BACK, the 1993 departure of AMAX was a turning point in recent Climax history. It marked a shift in emphasis from “swing producing” toward reclamation and broader environmental concerns, matters which, at elevations above 11,000 feet, would be no less challenging than mining itself. Frémont Pass is not a place anyone would choose to locate a major mine, much less reclaim one. But as mining folks say, they don’t choose where to locate mines; the placement of ore deposits does that for them.

At Frémont Pass, efforts in environmental protection and reclamation are complicated by three factors: water, climate, and the sheer size of the mine itself. Climax sits squarely at the headwaters of three major rivers — the Arkansas, the Eagle, and Tenmile Creek, the latter a major tributary of the Blue River that flows past Copper Mountain, through Frisco, and into Dillon Reservoir. As a major watershed, the Frémont Pass area receives an average of 270 inches (about 23 feet) of snow each year. That adds up to 25 inches of surface water annually, which translates to an enormous environmental responsibility.

Reclamation and revegetation are also problems, because the subalpine climate limits the frost-free growing season to a mere ten weeks. A final point is that Climax, over nearly 80 years, has mined and milled some 400 million tons of molybdenite ore, more than 99 percent of which — the waste, or gangue, portion of the ore — now fills three massive tailings ponds in the Tenmile Valley.

SOME 40,000 ACRE-FEET of water flow through the 14,000-acre Climax property each year. To put that number into perspective, consider that one acre foot of water equals 325,851 gallons. The annual residential water requirement for an average suburban family (and its lawn) is about one-third of an acre-foot. That means that the water flowing through the Climax property each year is enough to serve the residential needs of 120,000 families, or about 330,000 people. The Climax watershed now provides seven percent of Denver’s municipal water supply, and the city of Aurora leases an additional 3,200 acre-feet.

“Of those 40,000 acre-feet that flow through the mine property, interceptor canals divert 30,000 acre-feet of clean water away from our tailings ponds and into lower Tenmile Creek,” Cupp explains. “That leaves 10,000 acre-feet that contacts the tailings ponds — all of which we treat before releasing it into Tenmile Creek.”

The scope of the job of maintaining water quality is reflected in the fact that 8 of the 17 full-time Climax employees are assigned to the mine’s Water Treatment Department. Each year, Climax uses 12,000 tons of slaked lime (hydrated, ground limestone) obtained from Utah at a cost of approximately $1 million to treat water by precipitating out dissolved metals. The total cost to treat 10,000 acre-feet of impacted water is as high as $400 per acre-foot, or $4 million, per year.

“And that’s an ongoing expense year after year,” Cupp points out. “But we have an excellent compliance record and the water we release into Tenmile Creek meets all discharge standards.”

Climax has also transformed one of its smallest, but most problematic tailings ponds into a clean-water reservoir. In 1967, when it was running at full production mining its usual sulfide ores, Climax embarked on a brief, ill-fated effort to recover supplemental molybdenum from oxide ores using an acid-leaching process, while disposing of the extremely acidic tailings in a special impoundment near the head of the Eagle River drainage.

In 1993, Climax announced plans to convert this acidic oxide pond into a freshwater reservoir. Vail Associates, always looking for more water for municipal and snow-making use, quickly purchased the future water rights for $3 million. In a project that took six years, Climax pumped, excavated, and hauled the tailings from the oxide pond and consolidated them into one of the large tailings ponds in the Tenmile Basin.

Today, the former oxide-tailings pond, which was cleaned literally to bedrock, is the Eagle Park Reservoir. It has a capacity of 3,200 acre-feet of water and a live yield of 2,000 acre-feet per year, all of which meet drinking-water standards. The project earned Climax an award from the Colorado Mined Land Board for “outstanding reclamation involving water delivery to highly sensitive receiving waters” — the Eagle River.

Also in the early 1990s, Climax assessed its disturbed land area and identified some 1,000 acres that would not be needed for future mining. Today, Climax has reclaimed much of that land along the Colorado Highway 91 corridor and has planted 80,000 spruce, fir, aspen, and willow saplings. Using special plastic tubes to protect the young saplings from wildlife, Climax reclamation specialists have thus far achieved a survival rate of 80 percent — remarkably high for the harsh subalpine conditions.

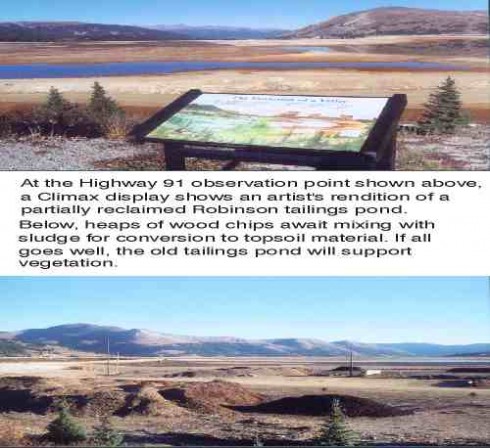

IN 1995, Climax took on another project — reclaiming the 600-acre Robinson Tailings Pond, the uppermost of the Tenmile Valley tailings impoundments and one that is prominently visible from Colorado Highway 91. The reclamation process required capping the entire pond with rock and soil to stabilize the surface and prevent wind from creating airborne sand and dust. To revegetate this surface, the soil and rock cap must be covered with lime and a topsoil layer capable of supporting plant growth. Rock was readily available, but the huge quantity of topsoil needed was not.

But then several municipal wastewater-treatment districts from Summit County got together and presented Climax with an interesting proposal. The districts faced costly disposal of growing amounts of sludge — the organic-rich solids remaining after municipal wastewater has been processed. It would be much cheaper if the districts could haul their sludge to Climax than it would be to dispose of it in landfills. Could Climax make use of the sludge?

This was the start of the ongoing and enormously successful Climax “biosolids” program. At Climax the sludge is mixed with a source of carbon, usually wood chips, which are also a recycled resource obtained primarily from Breckenridge-area developers who are anxious to cheaply dispose of downed trees. The sludge-wood chip mixture is then composted in a process that generates enough heat to kill any pathogenic organisms present. Because of the cold, subalpine climate, the composting piles must contain more woodchips than similar piles at lower elevations, and they must be larger so as to retain more heat. The year-long composting process produces a material ready for use as topsoil.

When Climax began its biosolids program, it received about 1,000 tons of sludge per year — enough to produce the topsoil needed to reclaim as many as 30 acres. The program has since expanded. It will soon utilize 5,000 tons of sludge annually and could last far into the future. To date, Climax has reclaimed 500 acres — more than three-quarters of a square mile — and it continues to reclaim an additional 60 acres each year. In 2002, Climax received the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Exemplary Biosolids Management Award for “outstanding use of biosolids to help rehabilitate large-scale, high-altitude mine sites.”

THE CLIMAX BIOSOLIDS PROGRAM has proven to be a win-win situation for the mine and the Summit County wastewater districts, and now even for places as distant as the Vail Valley, Buena Vista, Steamboat Springs, and Crested Butte. Interestingly, Leadville and Lake County do not participate in the program because it is cheaper to haul their relatively small amount of sludge to the nearby county landfill.

“There is no question that mining, by its very nature, impacts the environment,” says Cupp. “And Climax is a very large mine that operated for a long time. But we’re doing an excellent job with water quality. And reclamation is underway, but because of the climate and the extent of the disturbed ground, it’s going to take time.

“Frémont Pass will never look the way it did a century ago any more than the I-70 mountain corridor will ever look the way it did 40 years ago,” Cupp continues. “But we will reclaim all the ground possible. Final reclamation, however, must wait until mining is completed.”

And when will mining be completed? The better question might be, when will mining resume? The answer lies somewhere in the uncertain future of global molybdenum supply and demand, the needs of the steel-making industry which is driven by the global economy, and the longevity of the Henderson molybdenum mine near Idaho Springs, which is also a Phelps Dodge property. But Climax does sit atop 145 million tons of molybdenum ore, and Phelps Dodge believes that the resumption of mining is just a matter of time.

Today, Climax is hardly the economic giant it was in 1980 when it contributed 86 percent of all Lake County property-tax revenues. Yet it remains a substantial player in a downsized Lake County economy, providing an annual $1.3 million payroll and paying about a half-million dollars in annual property taxes each year.

The 20-plus years that have passed since the 1981 layoffs fall into two radically different phases. The first decade saw a desperate and futile attempt to retain a share of the molybdenum market through a “swing-producer” approach. The second and current phase focuses not on production, but on reclamation and maintaining water quality.

And this will probably be the Climax we’ll see for at least the coming decade, a giant mine with suspended production caring for 40,000 acre feet of water each year, reclaiming more of its disturbed land, and waiting for the day when it can do just what that premature Denver Post article implied: mine and mill more molybdenite ore.

Steve Voynick, who now abides in Twin Lakes as a full-time writer, once mucked at Climax. Among his many books is a history of the Climax Mine.