Article by Dick Dixon

Local History – May 2002 – Colorado Central Magazine

ONCE UPON A TIME, the American West was a contentious place: rough and tumble, violent and lawless and given to brawls and worse. There was the Texas War of Independence, the Mexican War, the Indian Wars, the Grange wars. And some of those early disputes were between counties.

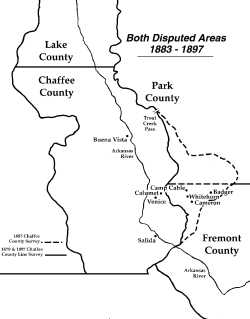

Chaffee, Park, and Frémont counties didn’t take up arms in the 1880s and ’90s, but they did struggle to take and keep territory — employing surveyors and attorneys, rather than soldiers.

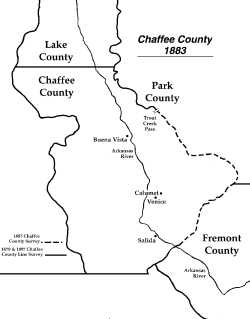

In this case, taxable property was the inducement. In 1883, a destitute Chaffee County ordered a survey deep into Park County hoping to acquire tax revenue from several large ranches and the railroad.

The land in question was a stretch of the Arkansas Hills (or southern Mosquito Range, if you prefer) between Trout Creek Pass and the Arkansas River. It never has provided much in the way of population or tax base to finance a county government — but to the beleaguered Chaffee County Commissioners it looked promising.

Thus Chaffee County tried to grab a piece of Park County, but Park County won that dispute.

But then Frémont County realized that it could claim a chunk of what nearly everyone had thought was Chaffee, since its boundary with Chaffee was defined, in part, by Park County’s boundary. And if Park County’s boundary moved west, then so should Frémont’s.

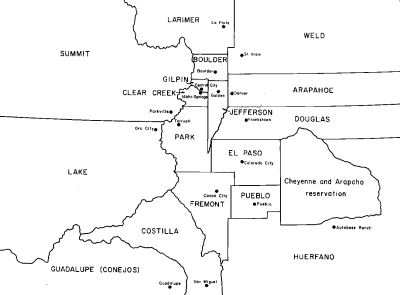

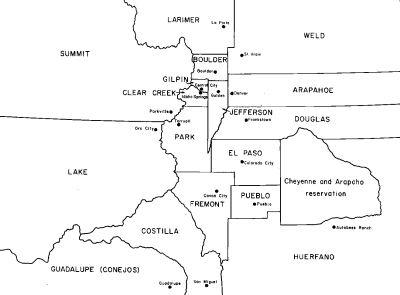

IT’S A COMPLICATED STORY that begins in 1861, when Colorado was organized as a political entity with a territorial legislature that divided the state into 17 counties, including Park, Frémont, and Lake.

Park has almost the same boundaries today as it had then. Frémont’s southern part became Custer County after a rush to Silver Cliff in 1877, but otherwise, its boundaries are little changed. But Lake County has really shrunk.

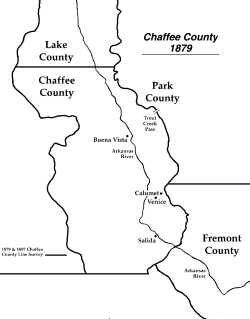

In 1861, Lake County stretched west to the Utah line, and south as far as Ouray. Over the years, new counties were carved out of this territory, and one of them was Chaffee in 1879. Chaffee inherited the southern part of Lake’s boundary with Park and Frémont.

The territorial laws that established county boundaries in the mountains were vague. There were many references to things like “the crest of the snowy range,” and courts often had to be consulted to determine whether “the snowy range” meant the Continental Divide or some other watershed ridge.

Due to such imprecise boundaries, Summit and Lake counties had to go through expensive and extensive litigation to determine which county would get the property taxes from Climax Molybdenum, and Grand and Larimer counties likewise litigated over which one really included North Park — today’s Jackson County.

The issue in our region started with a simple question: Where’s the southwest corner of Park County?

The territorial law specified that Park’s southern boundary was the “third correction line south” — a term surveyors could understand even if it doesn’t mean much to the rest of us — and “thence west to the summit of the snowy range, east of the Arkansas river; thence in a northerly direction along the divide between the Arkansas and Platte rivers.”

Such definitions offered room for interpretation. The usual course was for the counties to hire surveyors to set the line, based on their interpretation of the state law, and then formally agree on the results. And that’s what happened in 1882 and 1883 with the Chaffee-Lake boundary.

But things weren’t so simple for Chaffee’s eastern boundary, which ran through empty, mountainous, and broken country.

MEETING AT THE COUNTY SEAT in Buena Vista on Sept. 15, 1883, Chaffee County Commissioners C. A. Montross, J.A. Israel and J.M. Harvey approved a resolution that triggered 14 years of county line chaos, bitterness, and hard feelings.

“Whereas the dividing line between the counties of Park, Frémont and Chaffee appear to this board to be somewhat indefinite and this board being in doubt as to whether certain parties are taxable in this county…. It is therefore ordered that the county surveyor make a survey between said counties commencing at a point three miles below the mouth of the South Arkansas and running to a point at least six miles north of the third correction line.”

The portion of the line between Chaffee and Frémont counties was done jointly with Frémont County surveyors. The line they drew roughly followed the drainages of Badger Creek and Little Badger Creek, creating a large eastward bulge of Chaffee County into territory that had been — according to the legislature — Frémont County. There were few ranch lands in the area, no roads, no towns, and no mining activity, so it didn’t appear to make much difference where the line went.

Surveyors agreed. Using the creek drainages and ridgetops, they created a line that would be easily recognized if the area some day became inhabited and taxable. The joint survey ended at the northern boundary of Frémont County — the third correction line — and Frémont surveyors returned to Cañon City to draw maps and prepare reports.

But S.E. Day, the Chaffee County surveyor, was obedient to orders from his commissioners. He and his party continued north, deep into the broad, rolling country of South Park in Park County. With no logical termination point in sight, they angled west and then north toward Trout Creek Pass.

As early as 1879, the Chaffee County Treasurer had started annually billing ranches in the area for taxes, but the owners stubbornly refused to pay. They claimed they already paid taxes in Park County. The treasurer was persistent, however, and Chaffee County penalties and interest were piling up creating a bonanza — if it could be collected.

Contested Park County land included large ranches owned by the Mulloch Brothers, William Gribble, the Eddy Brothers, S. P. Gutshall, M. Biggs, Eddy and Bissell Livestock Co., South Park Land and Cattle Co. and several smaller homesteaders.

In 1883, Day and his crew surveyed a boundary that was generous to Chaffee County, and also diligently put as many miles of Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad track as possible in their county. Railroad taxes were the mainstay of Chaffee County school districts and towns.

On Dec. 19, 1883, Day reported to commissioners, and his maps and reports were immediately approved and filed with the Chaffee County Clerk and Recorder. Day was subsequently paid $1,066.

Protecting its territory, Park County returned fire with a survey of its own, and the two different boundary lines brought about 75 square miles of land into question.

The Park County survey results were delivered to Chaffee County on July 20, 1885. Chaffee County Commissioners replied Aug. 6, 1885, with “… a certified copy of the field notes of the survey of the boundary between Chaffee County and Park County. Chaffee County will recognize said survey as the true boundary line unless the same is changed by arbitration as is required by statute.”

Treasurers in both counties were as frustrated as the ranchers who — not knowing where to send tax money — used the conflict as an excuse to avoid payment to either county.

RANCHERS BROUGHT LITIGATION against Chaffee County and it grew hot enough that during its Jan. 26, 1888 meeting, the board released all the property in question from “liability to penalties and interest by reason of nonpayment of taxes from the date of issuance (some as early as 1879) until settlement has been effected.” The board promised to collect taxes for those and subsequent years “only if the settlement is favorable to Chaffee County.”

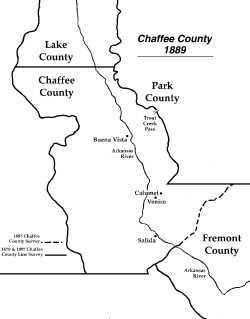

Although no specific reference was made to a case number, the argument was apparently heard by the U.S. Circuit Court, which relied on the 1861 Park County line. The ruling against Chaffee County came in December of 1888, and at their Jan. 8, 1889, meeting, Chaffee County Commissioners abated all taxes, delinquencies and penalties on property within the disputed territory. In addition,the board ordered a rebate of $211.12 in 1885 taxes for the South Park Land and Cattle Co.

Except for the Chaffee County and Park County Commissioners’ minutes and records of tax abatements, little of the Chaffee/Park dispute ever reached newspapers.

At that point, however, Chaffee County residents still accepted the Frémont County boundary line established in the 1883 survey as undisputable truth.

But Joseph W. Milsom, Frémont County Clerk, learned that after surveyors from both counties ran the 1883 line, it was immediately accepted by Chaffee County Commissioners, but Frémont County Commissioners, for some unknown reason, had never approved the 1883 survey. Milsom used this fact as the basis for his successful reëlection bid.

THE UNDISPUTED POINT on the boundary was a point on the Arkansas River three miles east of the mouth of the South Arkansas. From there, it was supposed to go up to the divide between Platte and Arkansas drainage — essentially, the southwest corner of Park County, rather than the 1883 survey’s point a few miles east of the Park corner.

That land had been mostly untaxable federal land. But the immense gold discoveries at Cripple Creek in the early 1890s had inspired prospectors to examine similar volcanic terrain in the hopes that it, too, would provide a bonanza.

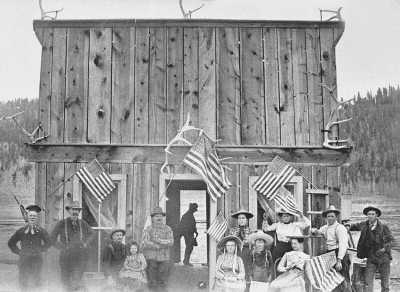

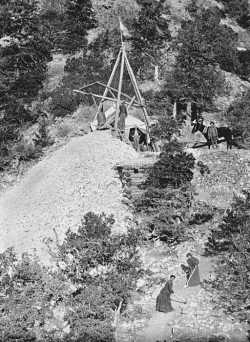

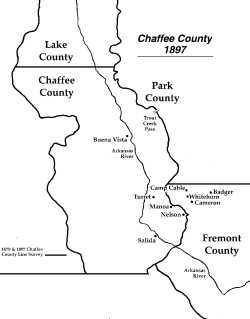

By the winter of 1896-97, prospectors from Cripple Creek had ventured west following what they called a “gold belt” of promising mineralization. Along the way, they founded Whitehorn, Camp Cable, Cameron, Badger, Badger City, Gold City, Hercules Camp, Minnman, Nelson and Manoa, which were mostly in the eastern part of Chaffee County as it was established by the 1883 survey.

Milsom figured he would be something of a local hero if he could place those promising mines — and their anticipated tax revenue — inside Frémont County, and that became his campaign promise.

THE NEW mining camps were supplied from Salida up Ute Trail, and were maintained by Chaffee County taxes. A 16-mile trip via good road to the northwest was the miners’ lifeline to county services in Buena Vista. Post offices in all of the new mining towns were registered in Chaffee County.

As Milsom campaigned, his promise was to enrich the Frémont County treasury. People in the fledgling mining camps, none more than 14 months old, were angered by the prospect of becoming part of Frémont County. Their easiest route to the county seat at Cañon City required a 75-mile journey (almost half of it on Chaffee County roads) to register mining claims and marriages, conduct litigation, seek law enforcement, have votes counted, or request school and road construction money.

Milsom tipped State Engineer John E. Field about the irregularity early in 1897. Chaffee County Commissioners registered an official protest on June 14 in a brief resolution that said Chaffee County “… does not desire any further survey made and the (Chaffee County) Clerk is notified to so inform John E. Field, State Engineer in Denver.” That was the only official mention of the event in minutes of the Chaffee County Commissioners.

The dispute went to court in September 1897.

As the suit was filed, Frémont County wanted about 55 square miles of Chaffee County territory. It included gold-mining camps at Whitehorn, Minnman, Cable City, Cameron, Badger, Badger City, Gold City, Hercules Camp, Nelson and Manoa. (When the dust and rhetoric cleared, Manoa and Nelson were the only two towns that didn’t land in Frémont County.)

The joint Frémont-Chaffee County line surveyed by crews from the two counties in 1883 had begun at the never-disputed point near the Arkansas River about three miles southeast of Salida. After angling north-northeast for several miles along Badger Creek and Little Badger Creek, the boundary zig-zagged 19.5 miles northwest along easily identifiable features such as ridgetops until it intersected the Park County line.

THE 1879 AND 1897 lines were similar to the 1883 line, but not identical. Although there was no argument about the starting point, the few degrees of difference at the northern end of the 1897 survey formed a sort of misshapen “V” with its point on the Arkansas River. The ends of the lines where they intersected the Park County line at the top of the “V” were about 10 or 11 miles apart. It was territory between the legs of the “V” that was in dispute.

Preliminary legal arguments were heard in Buena Vista, the Chaffee County seat, on Sept. 8, 1897, with Judge Voorhees of Pueblo presiding. G.K. Hartenstein, Chaffee County attorney, represented the county and S.J. Spray, county surveyor, was investigator for the case. They told reporters they were “confident the evidence they had collected would set aside the claim of Frémont County and forever establish the old (1883) line.”

Following opening barrages by both counties, the Whitehorn News explained: “The worst point against Chaffee County seems to be in the iniquitous decision made several years since, establishing the Park County line. In that case, Chaffee County neglected her side of the case and so was robbed of a good portion of territory.” (The editor hadn’t done his homework.)

The trial was moved to Pueblo — a neutral site — and argument continued on Sept. 18. Judge Voorhees again presided and Hartenstein represented Chaffee County. Judge Maupin and Judge Bradley, both from Cañon City, represented Frémont County. Arguments apparently concluded Sept. 21, with Voorhees taking evidence under advisement. The Whitehorn News explained a day later.

“The only serious obstacle to Chaffee County success is the probable unwillingness of the judge to conflict with the decision by which Park County robbed us of a considerable stretch of territory. If Frémont wins this case, it simply means a fight will be at once begun to make a new county division whereby Pleasant Valley (the local name for the area) will be placed in Chaffee County where it naturally belongs and Salida made a County Seat. There is no justice in (Frémont County’s) present claim and if it is allowed, she will be the loser when a fight is made in the legislature.”

By late September, 1897, Field and his survey crew were nearly finished and they continued work despite protests and threats from residents. Their line had passed west of all but two of the mining camps surveyed thus far — moving them into Frémont County.

Caught in the middle of a vociferous dispute between two counties, State Engineer Field claimed that his only choice was to revert to the original boundary as it was established when Chaffee County was created in 1879. The 1883 survey line was no longer applicable, and eastern Chaffee County residents were furious with Milsom.

The Whitehorn News, Turret Gold Belt and Salida Mail editorially took up the fight, berating Milsom for his political platform and attacking Frémont County for its earlier failure to accept the 1883 survey.

MEANWHILE, RESIDENTS continued to consider themselves part of Chaffee County, even though Chaffee wasn’t sure whether it could provide money for road improvements and schools in that region.

But when they needed something done, citizens often did it through private subscription or volunteer labor, rather than ask Frémont County.

Oct. 1, 1897, was not a good day. Field’s survey crew passed on the “wrong” side of Whitehorn, undeniably placing it in Frémont County. That same day, Frank Charles fell 50 feet into his own mine shaft, breaking an arm, a leg, and several ribs. To make it worse, he wasn’t found for 19 hours and “suffered terribly” in the interim because he remained conscious.

More heartening was the birth that day of Anna Marie Alloway, “Bright as a dollar” according to The Whitehorn News. She was the first child born in Whitehorn. Her parents were Mr. and Mrs. W.H. Alloway.

As the court battle developed, Whitehorn residents wondered where to seek money for a school. With 27 school-age children in town, people applied to Chaffee and Frémont counties. The plea was refused by each. Residents — not just parents — pooled resources to pay a teacher. They donated use of a building, and school started the third week in October.

In mid-October, Judge Voorhees announced his decision — in favor of Frémont County. But evidently there was an appeal to the Colorado Supreme Court, because, map notations on U. S. Post Office Department documents show the high court upheld Voorhees’ decision in late November 1897.

The News didn’t run a story about the decision against Chaffee County — nor did any other southern Colorado newspaper. It was as if the event was of no importance to anyone if it didn’t favor the fledgling camps.

Records of all the court proceedings (and the surveyors’ field notes) disappeared as they were shuffled from one courtroom to another, and they haven’t been found yet. Details of the arguments and final decision would be helpful to county officials, surveyors and school districts today.

Mining camp residents ignored the ruling. They continued to think of themselves as Chaffee County residents. Post offices were registered in Chaffee County as were almost all mining claims. Newspapers, including the Pueblo Chieftain, continued to blast Milsom, Frémont County, the courts and the judges for their “ignorant” decision.

CONFUSION ABOUT county location for the several towns spread to the Post Office Department. On Jan. 22, 1898, one A. Haake, a post office topographer, was attempting to draw more accurate maps of postal routes and ran into a snag with the Frémont-Chaffee County towns. He wrote to Louis Nell at the Surveyor General’s Office in Denver:

“I find I am in conflict with recent statements from postmasters as to the county location of Skinner [Badger] and Whitehorn post offices. Your correction places these post offices in Park County, whereas they are said to be in Chaffee County by each of the postmasters answering my special inquiry, these being the postmasters at Skinner, Whitehorn, Buena Vista and Fairplay.”

PART OF HIS CONFUSION came from a Jan. 10, 1898, hand-drawn map that inadvertently left out the east-west boundary separating Park and Frémont counties. A subsequently corrected map cleared that part of the mystery. Haake’s continued confusion stemmed from the refusal of residents to give up their accustomed affiliation with Chaffee County. All his sources continued their head-in-the-sand attitude.

“The postmaster at Skinner [Badger] has advised me that all land transfers and other transactions for his section are recorded in Chaffee County and that the votes in the election of last November were returned in said county. The answer of the postmaster at the county seat [Buena Vista] confirms the postmaster at Skinner’s statement. Will you please look further into this matter and kindly communicate to me what you may ascertain? I wish to be perfectly sure of the facts before notifying the Postal Guide of changes in county location not confirmed by the postmasters interested. The bonds of these postmasters are made out in Chaffee County.”

After more than 36 months, the Whitehorn News reluctantly and quietly admitted defeat with Volume 4, Number 19, Jan. 11, 1901. Without fanfare, headline or story, editors rewrote the masthead, changing the Whitehorn location of the paper from Chaffee to Frémont County.

DESPITE EARLIER THREATS of appeals to the Colorado Legislature or even the U. S. Supreme Court, heartsick residents of Whitehorn and the other camps never rallied for the assault on Judge Voorhees’ decision.

By the end of 1900, their hoped-for large ore shipments hadn’t materialized. Miners drifted toward more promising discoveries at Turret about five miles west. It was apparent there was not enough wealth in the district to make argument worthwhile.

On May 24, 1902, fire destroyed much of Whitehorn. There weren’t enough people left to renew the fight and Chaffee County Commissioners ignored pleas from residents who wanted the battle continued — there was nothing there of value for which to fight.

By 1904, all the towns were abandoned except Whitehorn. It continued until about 1916 before losing its postal designation and general store. Some people, including most newspaper editors, believed the demise of Whitehorn and the other towns had more to do with lack of access to Frémont County services than because of a lack of valuable gold ore.

Although Frémont County Clerk Joseph Milsom won reëlection in 1897 and acquired a large chunk of territory for Frémont County, the rich tax base of bonanza gold mines he promised evaporated before it could be tapped. He declined the nomination for a fourth term. His decision undoubtedly was influenced by venomous editorials shot in his direction by Chaffee County-based newspapers in Salida, Turret, and Buena Vista. Although the Whitehorn News was no longer officially in Chaffee County, its voice, until it died in 1902, led scathing attacks on Milsom and Frémont County.

Frémont County Commissioner Keith McNew, who today represents the western portion of the county, is familiar with the story. He said the annexation was “… mostly political. [Milsom] was seeking reëlection and there were several new mining camps in the area that looked pretty promising. None of them ever produced anything — not even by the time Milsom was reëlected [in 1897].

“He thought if he could get those mining camps into Frémont County, there would be a big tax advantage to the county. As it turned out, they were all pretty much gone within a short time after the election. His plan just kind of fizzled,” McNew said.

Frémont County isn’t making or spending big bucks on the area today.

“There really isn’t anything in that area today but Bureau of Land Management land and a little private property. Mostly it’s BLM,” McNew said. “There are some short sections of Frémont County Roads 2 and 12, and a little bit of CR 11, so maintenance doesn’t cost all that much. I don’t know in dollars. As far as income from taxes, I’d have to say it’s a wash — there isn’t much income, but it doesn’t cost us much for services either,” he said.

Dick Dixon has written extensively about the Turret-Whitehorn area. After retiring from teaching journalism and American history at Salida High School, he is copy editor at the Salida Mountain Mail.