by Ron Sering

With the BLM’s announcement of a lease auction of nearly 800 acres in the vicinity of Mt. Princeton hot springs, the area could be the site of the state’s first geothermal power plant. Not everyone is happy about it.

Geothermal energy uses heat generated by volcanic activity beneath the earth. Applications include direct use, such as collecting hot water in a pool, or heating buildings such as homes or greehhouses, or, in a unique local case, for aquaculture to raise fish and reptiles. Colorado Gators in Mosca started as an aquaculture facility, later adding alligators which have generated tourism.

Geothermal generation of electricity began in the Lardarello region of Italy, where a power plant has been in steady use since 1913. The plant generates approximately 4.8 billion kilowatt hours per year and serves more than a million homes. The facility creates steam by pumping cold water onto hot rocks below the surface, which in turn drives turbines to generate electricity.

Colorado is a part of a group of Western states with high heat flow that includes California, Nevada, and Idaho. Homegrown geothermal power plants include the Geysers region of California, which uses natural steam geysers to supply enough power for a large city. The energy source produces little or no emissions; unlike other renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, geothermal energy offers 24/7 availability.

The technology is not without drawbacks. A recent project in Basel, Switzerland attempted to access geothermal resources in a similar method to Lardarello, but with drilling and injection of water at depths exceeding five kilometers. “At that depth,” says Matt Sares, Deputy Director of the Colorado Geological Survey, “the rock is not very porous. You have to fracture the rock layers to inject the water.” Following earth tremors in the area, the facility was shut down for further analysis.

New technology makes it possible to generate power with water at a temperature below 400 degrees. These plants pump the water to the surface, where it passes through a heat exchanger containing a binary fluid that boils at a lower temperature than water. This in turn produces the steam that drives the generators.

“The water is then reinjected into the ground,” Sares said. Sares stressed that well depth in this application is significantly shallower than at the Basel site and does not involve the fracturing of rock layers.

Current binary facilities include a nine megawatt facility in Soda Lake, Nevada, and a 35 megawatt facility near the Mammoth Ski area in California. Other facilities exist throughout the West and in Alaska.

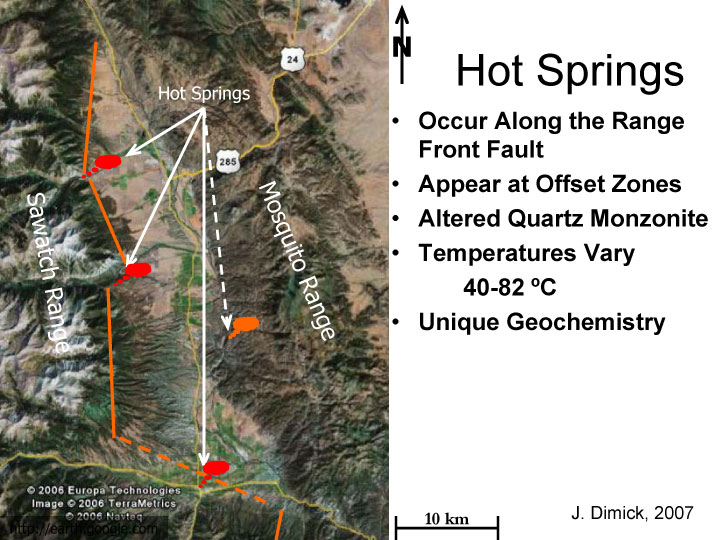

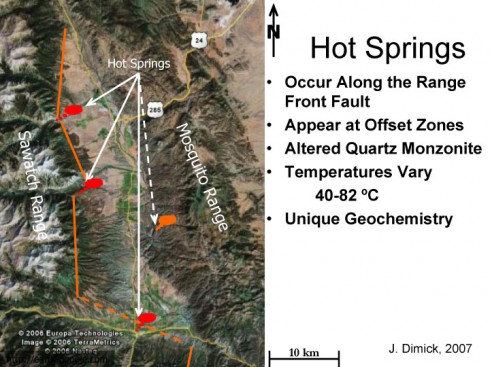

The extent of Chaffee County’s geothermal resources was measured by Amax Exploration in the 1970s. The effort ceased with the return of cheap petroleum in the 80s, and because the technology of the time required natural steam to generate power, rather than the hot water found in Colorado. Subsequent research in the area around Mt. Princeton by the Colorado School of Mines indicate favorable potential for geothermal development using binary technology. “It is an area of exceptional heat flow,” Sares said.

Mt. Princeton Geothermal LLC., a local company headed by Salida native Hank Held and Nathrop resident Dr. Fred Henderson III, has conducted its own series of thermal gradient tests, which measure heat change by depth to provide an indicator of potential for a geothermal power plant. The results only strengthen the possibilities.

Colorado lags behind other Western states in the development of this resource. “We have a high heat flow in Colorado,” Sares said, “but no power generation.”

The state of Colorado hopes to change this. Geothermal power generation is part of an effort by the Governor’s Energy Office to increase the state’s renewable energy usage. In his final state of the state address, Ritter called for an increase in the state’s net renewable energy usage to 30 percent in the next decade.

The effort includes sponsored research and grant funding for wind and solar energy development, as well as geothermal. Toward this end, the state provided partial funding for the recent geothermal research.

In a recent presentation in Buena Vista, BLM National Geothermal Program Manager Kermit Wetherbee outlined details of a planned ten-year lease for 799.2 acres, parcel COC73714, in and around the Chalk Cliffs area near Nathrop. During that time, lessors may drill exploration wells to determine if there is sufficient heat flow for a binary power plant, and possible resource development. Wetherbee outlined the phases:

• Exploration

• Drilling

• Utilization and production

• Reclamation and abandonment.

State and county governments each receive a 25% distribution of lease revenues, a boon for stretched budgets. Wetherby estimated an average price for past leases at $39 an acre. The developing company pays royalties for any resource utilization, in similar fashion to oil and gas leasing.

Depending on the results, tentative plans are to build a 10 megawatt binary power plant. The actual location, if any, is undetermined. “The plant must be built close to the resource,” Sares said.

Greg Shoop, acting director of the BLM’s newly formed Colorado Front Range District, stressed that “issuance of the lease does not automatically mean there will be development.”

“Each phase is subject to environmental analysis under NEPA,” Wetherbee added. The National Environmental Policy Act requires federal review the environmental impact of possible exploration and development of public lands. All phases require an environmental impact statement, a lengthy process often taking years.

It is just such impact that concerns many area residents about effects on area water rights, water quality and on existing geothermal wells. Concerns also include possible effects of such industrial activity on an alpine environment. Sares explained that binary power plants require either water or air cooling. “Generally, air cooling is used, so that there are no steam flumes. Inside the plant, it is possible to have a conversation. Outside and beyond the perimeter, it’s akin to less than a lawn mower.”

“Well, see, I really don’t want to hear a lawnmower all day long,” Nathrop resident Gary Masden said.

Colorado water law prohibits any use of ground or surface water that injures the water rights of others. “Injury includes any reduction in quantity, temperature, or quality,” said Kevin Rein, of the Division of Water Resources, which oversees the issuance of well permits statewide.

In a statement, the Division stated expectations that geothermal development would be nonconsumptive because “it allows for the preservation of the geothermal resource in terms of quantity and temperature. Second, by using the geothermal fluid nonconsumptively, by reinjecting it into the same formation as that from which it was extracted, the user minimizes the potential for impacts to surface streams and other wells.”

A public comment period on the proposed BLM lease began in December. In one protest letter, Mt. Princeton Homeowners Association (MPHOA) member Eva Plante wrote, “I am extremely concerned about the impacts of this geothermal project to the MPHOA drinking water supply.” In her letter, she observed that “Heywood Springs (the groundwater source for area drinking water) is within 1000 feet of parcel COC73714.”

Plante’s letter concluded by calling for an environmental analysis and a quantitative health risk assessment, with reports submitted to the MPHOA prior to commencement of drilling.

The comment period ended on January 27, but not the process. “This process is a long way from over,” Shoop said. “I can tell you that most of the comments are that I don’t like the idea.”

Shoop stressed the importance of citing reasons for opposition. “It’s not enough to just say, ‘I’m against it.’ You have to say why.” Shoop said that even at this late date, it is possible for the auction to be withdrawn.

Regardless of the outcome, the resources will still be in the ground, still rife with potential. “Geothermal energy is a valuable resource for Colorado,” said State Senator Gail Schwartz, who represents the region. “The question is, where and how?”

The auction is set for 9 a.m. on February 11, 2010, at the Bureau of Land Management, Colorado State Office at 2850 Youngfield Street in Lakewood. Registration begins at 8 a.m.

Ron Sering has published articles in various newspapers, and magazines as diverse as Inside Ecuador and Ceramics Monthly. He lives in the wilds of Howard with his wife, the artist Christine Marie Davis and their beloved Jack Russell terrier.