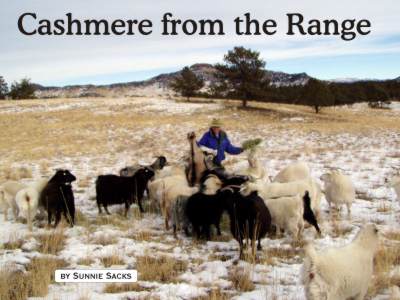

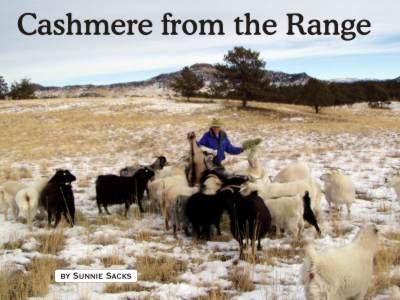

Article by Sunnie Sacks

Agriculture – March 2005 – Colorado Central Magazine

WHEN SUZANNE ROTH was operating her home interior design company, Red-bird Design, in Evergreen, she never dreamed that one day she would be living in Guffey, or that she would be raising goats, combing them and selling the cashmere, the winter undercoat or down of the goat, to spinners, knitters and weavers.

After living in Evergreen for 25 years, Suzanne and her husband Fred were ready to leave. “Evergreen was getting too over-built for us. We were looking for a remote place to live when we found Guffey,” said Suzanne.

In 1997, they bought land near Guffey and named it Jabberwocky Farm. By the end of 1998 the Roths had purchased three goats, a nanny and two kids. Suzanne was on her way to building a herd.

The main reason Suzanne choose goats was because they were fiber-producing animals. She had only had experience with horses in the past, so this was an exciting experience for her. Today on 75 acres, divided into three pastures, Suzanne has 37 goats.

“I have always had a love for fiber. The idea of having animals to grow the fiber and to be able to process it intrigued me. Cashmere is such a luxury fiber, that I was drawn to it. We got the goats, and I fell in love with them. My breeding stock stems from Spanish, Tasmanian and Australian goats. There is not a cashmere breed, it is just a goat that can grow long fine down,” Suzanne said.

Goats date back to ancient times in Asia, and are the oldest domesticated livestock. For centuries they have provided things necessary to man’s survival in the form of meat, milk, hides, fiber and companionship. Historically, the cashmere producing areas were in the Himalayan region. Western clothiers bought cashmere in bulk mainly from India, China, Iran and Afghanistan. Cashmere was once considered the fiber of kings, and it is said to have lined and curtained the Arc of the Covenant of the Old Testament.

IN THE FIRST PART of the 19th century European immigrants introduced goats when they settled in the Southwest. These “Spanish” goats, as they were called, lived on large tracts of arid land, where nothing else would thrive. They ran wild, with the exception of once a year when the herds were rounded up and the young goats were sent to a meat market.

Australia has a similar history. Immigrants settled on farms in the Outback, but some of the farms failed and the goats escaped and ran wild. In the late 1970’s, the Australians began to notice that this environment had produced a strong animal that had also developed a luxurious undercoat of down which protected it from the harsh climate of the Outback. With this discovery the Australians felt that they could establish a new industry which could lucratively be exported. The wild goats were captured and selectively bred to produce commercial cashmere.

In the late 1980’s a few Australian goats were exported to the United States. In the search for suitable mates it was realized that the goats in the Southwest already had much the same undercoat as the Australian goats. The “Spanish” goats were taken from their harsh environment and fed well, but the offspring did not have the same fine, lush undercoat as did the wild goats. It was realized that the fiber in goats was not just controlled by genetics; environment and nutrition also played an important part in growing the coveted down.

When the goats were taken from the arid Southwest and sent to New Hampshire, Washington State, or Colorado, they produced coarser and straighter, yet still luxurious, fiber.

Today, the United States is producing American grown cashmere, but on a very small scale. Jabberwocky Farm is one of three goat farms in Colorado that supplies cottage industries.

In order to pursue her trade, Suzanne dehairs her goats, has the wool processed, then spins part of it into yarn and sells the other as roving, which is cashmere that is not spun. The process of de-hairing the goat is done by one of two ways: either by combing out the down, or by shearing. Suzanne prefers combing it out. She starts combing in January as the goats start letting their hair down as the days get longer.

“I enjoy each step. First I comb the goats. All goats have undercoat, but some are bred to grow longer under-down. At the beginning of January through March, I comb each goat twice, but I wait two to four weeks between combings. It is labor intensive, but I have a lot of friends who come over to help. I don’t shear the goats because our winters are too cold to shear them. I don’t believe in doing that to them,” she said.

THE HAIR IS THEN SENT to Canada to be processed. “I’m really into American made, but I haven’t been able to find a mill in the U.S. that can process it like the one in Canada,” said Suzanne.

The goat hair Suzanne sends to the mill is processed into a loose rope-like shape by removing the guard hair, which is separated so that the cashmere will retain its softness. In order to turn the down into roving, the processor lines up individual fibers so that they are all going in one direction. Suzanne has the cashmere spun into yarn or left as roving, which is primarily used by hand spinners. Using a spinning wheel, spinners can process their own yarn to use in knitting or weaving or on looms.

The final step in processing the yarn for sale is to dye it. Suzanne has started dying some of her fiber, and is experimenting with different colors to create beautiful yarns.

Garments made from cashmere are very soft, warm and long-wearing. Though not as strong as wool, cashmere is softer to the skin and out-wears wool. A variety of textiles can be made from the undercoat: including knitted garments, which are made from the longest, finest down, and woven fabrics, which are made from the shorter down. The separated guard hairs are used to make rugs or for a hair canvas used in creating tailored garments.

“I direct my business to knitters, spinners and weavers. My market is basically for cottage industries. The fact that it is Colorado-grown cashmere makes it a special thing,” Suzanne said.

Though Suzanne does weave her own yarn, she doesn’t sell her finished work at this time. “Weaving gives you the ability to blend fibers. You can take two separate fibers and weave them together. With textiles, there are unlimited things you can do. I don’t sell finished pieces yet, but the next step would be for me to make garments,” she said.

At this point Suzanne sells her cashmere to fiber artists in Colorado, but she plans to have a website up by this June to expand her market.

Suzanne is a member of the Friday Fibers, a regional group of women, which currently averages 20 weavers, spinners and knitters. The women gather in different members’ homes the first Friday of each month. These women come from Castle Rock. Lake George, Guffey, Florissant and Divide to spend the day working together on their current fiber project. “It is very uplifting especially to see what other people are doing. It’s a great way to learn — and people are so giving,” Suzanne said.

This past summer a Spin-off event organized by the spinners of Friday Fibers was held at the Grange in Florissant. It included the spinners group, Twisted Sisters, from Salida; 30 spinners brought their spinning wheels and spun yarn together for most of the day. Spinning demonstrations were held for the public.

FIBER IS NOT THE ONLY PRODUCT Suzanne’s goats provide, however. “As a sideline, I make goat milk soap. I have one milk goat for the soap. It has wonderful skin softening qualities and essential oils. I sell it at the Caldera Gallery in Guffey, at fairs, and to family, friends and neighbors,” she said.

Suzanne plans to continue to increase her herd using her three bucks for in-house breeding. She would like to build a herd of 50, then stop because she doesn’t want the land to be eaten down by too many goats. By rotating the goats among her three pastures Suzanne is able to keep that from happening. To keep her herd selective, she sends the wethers (neutered males) to a meat market in Calhan, timing market day to coincide with Hispanic celebrations.

“I am so fortunate to pursue my love of raising goats every day,” Suzanne concluded. “Their antics bring a smile to my heart (most of the time). It is very satisfying to know that when the cashmere from my herd is turned into yarn, it will continue to bring joy and warmth to others who create and wear items made from it. I am so happy to accomplish this in the beautiful Rocky Mountains with the people and the critters I love.”

You can contact Suzanne at 719-689-9502

Sunnie Sacks free-lances from Guffey, which may be the closest post office to the actual center of Colorado.