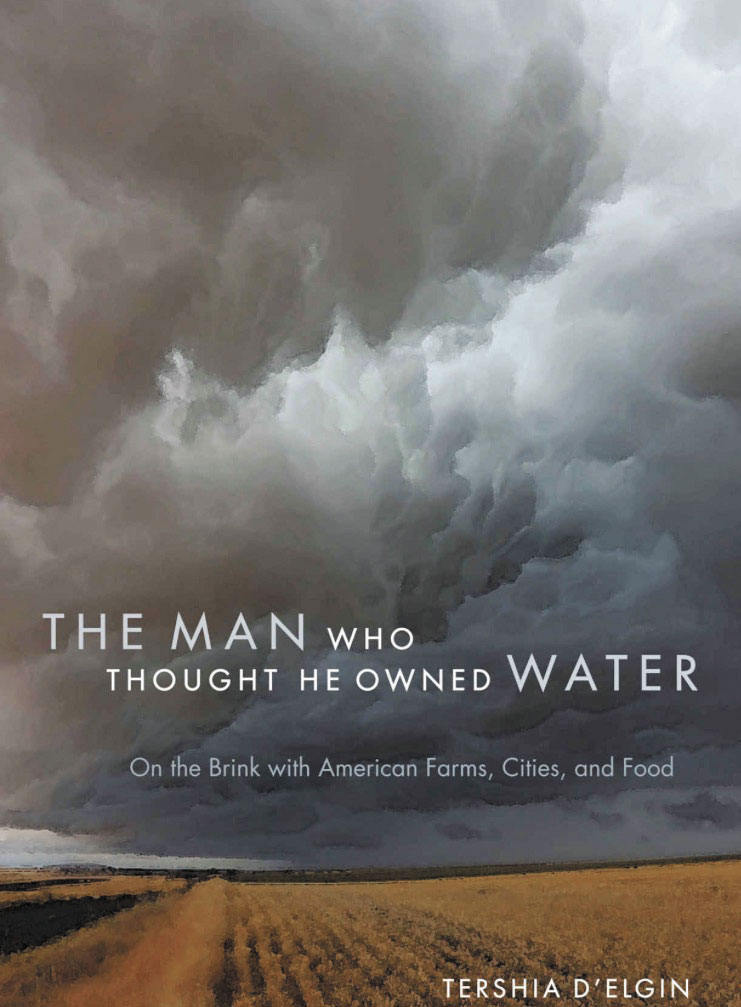

By Tershia D’Elgin

By Tershia D’Elgin

University Press of Colorado, 2016

978-1-607-495-9; 287 pp, $29.95

Reviewed by Virginia McConnell Simmons

Although Central Colorado is the birthplace of three of Colorado’s major waterways – the South Platte, Arkansas, and Rio Grande – who owns the water seems puzzling except among water managers and farmers. Most consumers simply take it for granted that the liquid stuff for sinks and plastic bottles, rafts and kayaks, fishing, skiing resorts and wells will always be there. To get an inkling of how change can happen, read The Man Who Thought He Owned the Water, with its subtitle On the Brink with American Farms, Cities, and Food.

The author, Tershia D’Elgin, writes a compelling biographical account of what happened to her own father in the Platte River Valley near Greeley. A great-grandson of Colorado Governor Benjamin Eaton, Bill Phelps begins with ambition aplenty and surface water rights that promised success at Big Bend Station. Where he ran amuck was in the assumption that he, like many of his neighbors, could increase productivity by using wells that delivered underground water.But the state was developing plans and rules for management, while the state engineer, Hal Simpson, was using a different set of rules to keep ground-water users in business. With the old rules no longer applicable or legal, wells in the Platte Valley and elsewhere were shut down. The rest of the story is about the struggle and change that ensued. Add to it the devastating drought of the early 2000s and the 1,000-year flood of 2013, and you have the Platte Valley’s perfect storm.

[InContentAdTwo] In the meantime, burgeoning Front Range cities, their lawyers and water brokers had been aggressively acquiring every water right that someone – anyone – would sell. That includes the water that originates in or is sent through Central Colorado. It also includes water supplies that were over-appropriated from the beginning of Colorado’s state history.

The San Luis Valley can provide a different example about sucking water from an aquifer. Forced by state rules to stop gulping its ebbing underground water for irrigation, subdistricts in the Rio Grande Water Conservation District have knuckled down to the task of formulating a plan that is intended to recharge aquifers and will cost farmers and ranchers money and fallowing. D’Elgin does not discuss this historic development in Central Colorado. Contention in Lake County does appear as an example of recreational versus agricultural litigation, though, and Park County gets one brief mention.

[InContentAdTwo] Many general readers of this book will appreciate the abundant information about water law and practice in numerous boxes beside the text. Inclusion of some environmental issues, such as the survival of frogs, has importance but possibly belongs in a different book; the author clearly has deep knowledge and concern about the environment, but one volume can contain only so much information before wearying its readers.

In the back of the book are a glossary and notes. No index is provided, although one would have greatly enhanced the volume’s usefulness. The author’s choice to call the titles of chapters “Spectacles” is an idiosyncrasy that’s easily ignored.

With her informal style, D’Elgin’s narrative makes engaging reading, and her insight into Colorado’s water issues are important. Meanwhile, the population keeps on growing while agricultural land shrinks.

This is a book that I highly recommend.