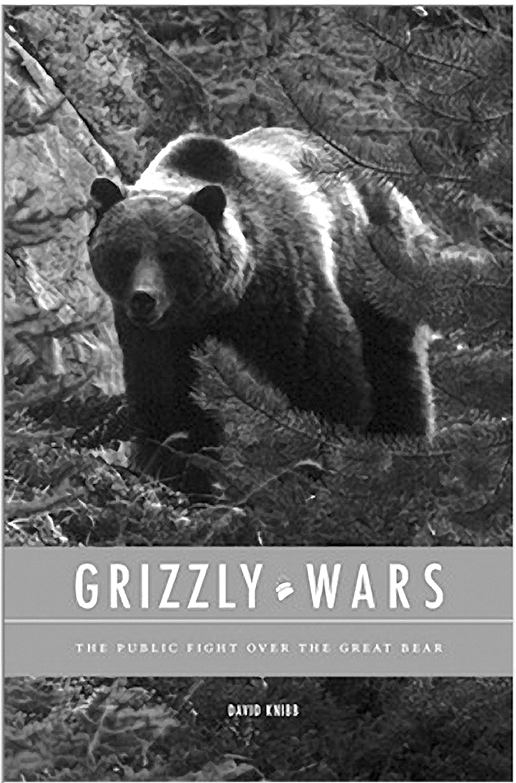

By: David Knibb

Eastern Washington University Press: 2008

ISBN: 978-1-59766-037-2

Reviewed by Eduardo Rey Brummel

Grizzlies, like wolves, are “NIMBY” critters. They are iconic to our images of “the wild west,” and our lands seem a sham in their absence; yet it seems the majority want them, “out there,” away from their own backyards and stomping grounds. Grizzlies can also, like wolves, be elusive and wary of humans, making their existence, and their numbers, difficult to prove.

Once upon a time, grizzlies numbered around a hundred thousand, their territory stretching from the Great Plains to the Pacific, from the Yukon to Mexico’s Sierra Madres. Fur trading during the early 1800s was the first devastating blow delivered to the great bears. Development of the wild frontier continued the decimation, as well as fragmenting grizzly populations, separating them into “islands.” When sheepherding began, the slow and dumb buffet line of mutton was more than opportunistic bears could refuse so sheepherders, subsequently protecting their flocks, dealt another telling blow against the grizzlies.

On July 28, 1975, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, acting under Nixon’s Endangered Species Act, categorized grizzlies as “threatened.” Other than in acts of self-defense, it became illegal in the lower forty-eight states to kill one. This was the first step in their recovery. In his book, Knibb records in thorough detail the backslide-riddled battle of state and federal biologists, as well as others, to return grizzlies in the Cascade Mountains to sustainability.

The cliché says we fear what we don’t understand. In the grizzlies’ absence, myths and fears about them germinated, sprouted and grew. (Again, much like with wolves.) Time and again, this out-of-proportion fear prevented even the teeniest advance. One night, the federal agent presiding over a public meeting in Okanogan, Washington, received nine death threats that same evening, when soliciting feedback about increasing the local grizzly population. Not that governmental agencies were any less fearful or human: “It took four years of haggling to agree on the color and wording for a warning sign about bears.”

This book could have been so much more dry and dense, with its coverage of local, state, and federal shenanigans, the repeating triumphs of politics and good-old-boy business-as-usual over solid biological science. It’s high credit to Knibb this book reads much like a thriller. With a sure pen, he inserts enough subtle humor, lightness of story-telling, and coy understatement to provide the moisture that prevents Grizzly Wars from becoming either soda cracker dry or cement dense. This Seattle lawyer also wrote, Backyard Wilderness, about the Cascades’ Alpine Lakes Wilderness and the congressional battle regarding it. I’ll bet this earlier work is at least as enjoyable.

Eduardo Rey Brummel has seen two or three bears in his life. None of them grizzlies.