Article by Lynda La Rocca

Local Artist – October 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

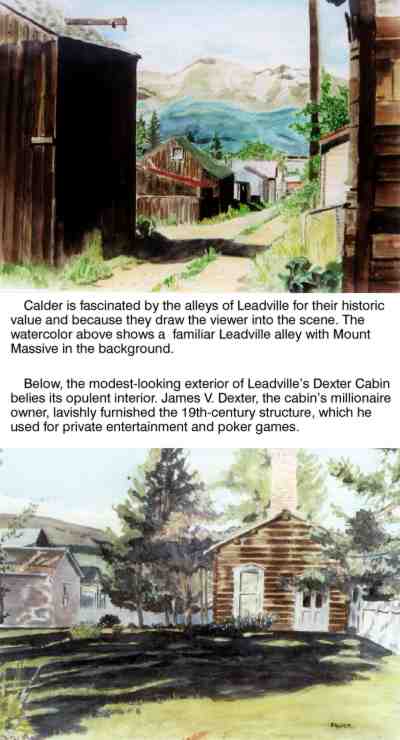

AT FIRST GLANCE, the alleys separating Leadville’s weathered, wooden outbuildings from the backs of its Victorian, shotgun-style houses might seem an unlikely subject for artistic endeavors.

But in the hands of artist Robert W. “Bob” Calder, these scenes of the Cloud City at its most authentic are transformed into watercolors that lead viewers along the dusty paths of Leadville’s frontier mining heyday.

“I want to make a record of Leadville, the real Leadville, before it’s all gone,” Calder says of his focus on depicting the city’s past through his art. “Leadville has so much character, so much that’s unique and historic. These alleys, the tailings piles, the old wood, the mine buildings, they’re like little cameos. And they’re portraits of Leadville that need to be preserved.”

A Colorado Springs native, Calder, 48, moved to Leadville in 1974 to become — not surprisingly — a miner.

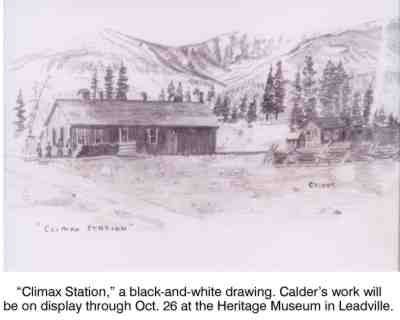

“I was always fascinated by tunnels,” he says with a grin. And four years underground at the Climax molybdenum mine provided plenty of opportunities to indulge that fascination. At Climax, Calder rose to the rank of hang-up timberman, a particularly dangerous job that involves clearing blocked ore passes by carefully placing dynamite at the point of a “hang-up,” then beating a fast retreat — knowing all the while that tons of rock can let loose before safety is reached.

Calder spent a decade working for the Leadville Mining & Milling Corporation and was also employed as a contract miner in Idaho Springs, and in Summit, Park, and Lake counties. He even lived, for a time, in a trailer at the remote London gold mine high in the Mosquito Range in Park County.

As mining jobs grew increasingly scarce, Calder embarked on a second career as a Certified Registered Locksmith, opening Lockworks of Leadville on East Sixth Street eight years ago. “I wanted to be of service to people here in town,” he says of his current profession, “and I was pretty lucky to roll into this.”

When not engaged in locksmithing or at his second job managing the local movie theater, Calder can usually be found pursuing his major passion: art.

“I was always interested in art, and I was always drawing, even as a little kid,” he says. And a class trip to the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center to view an exhibit of western art intensified his interest. “I was just astounded by what I saw,” Calder remembers. “I thought those paintings were the coolest things.”

Still, it took a while before Calder made the switch to painting. He concentrated instead on pen-and-ink drawings until 1980 when, while working as a miner, a chance discovery helped determine his artistic direction.

“I found these watercolor paints, the kind for kids in the rectangular box with one dinky brush,” Calder recalls. “Here I had this little paint set, so I just decided to use it. I bought some watercolor paper and first tried to reproduce postcards.”

Soon he was painting snow-covered peaks, rocky outcrops, and sunlight reflecting on alpine lakes, sometimes photographing or sketching summer vistas to use as inspiration for paintings during Leadville’s long winters. He also produced scenes of local mines and front-facing views of Victorian-era buildings.

At the same time, Calder found himself intensely drawn to the aging structures lining Leadville’s alleys. He began creating his own interpretations of a part of the city that most people either never notice or choose to ignore, slightly altering details in “portraits” that are nevertheless realistic enough to lead admirers of his work to the actual alley.

“I love the alleys because they make me feel like it’s another time, like I’m back in the Leadville that existed 100 years ago,” Calder enthuses. “Plus, in terms of the public, people enjoy something that leads or draws them into a painting, and that’s exactly what alleys do.”

Though Calder has dabbled in oil painting and still works with pen-and-ink, along with pencil and charcoal, watercolor remains his favorite medium. “It’s easy to clean up,” he jokes. “I can just wash the brush off and walk away.

“Seriously, I like color and I like the way watercolor looks and flows,” he continues. “Watercolor gives me very vivid colors. I don’t use a purple, for instance, that looks awful close-up but great from far away. With watercolors, I can stay true to the reality of the color.”

Apart from one five-week course at Colorado Mountain College, Calder is completely self-taught. (“If you just do it, you figure out the technique,” he observes.) But he counts among his major influences the works of western artists Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington, Impressionist Claude Monet, 19th-century American naturalist painter Winslow Homer, whose free-flowing, almost Impressionistic watercolor technique was considered the most advanced of its time, and 20th-century great Andrew Wyeth, whose subtly shaded, neutral-toned watercolors capture rural Pennsylvania and New England scenes.

“I really love Wyeth because he gives you the feeling of being in another age, and he recorded another era, like I do,” Calder explains. “But Winslow Homer is probably my favorite artist. His watercolors inspired me to paint even more watercolors myself.”

Despite his enthusiasm, Calder is also his own worst critic, frequently finding fault with his finished product. “There’s almost always something I want to change or something I wish I’d done differently in a painting,” he notes.

It’s an attitude definitely not shared by the viewing public. Last fall, Calder was invited to show his watercolors at the Timberline campus of Colorado Mountain College. And through October 26, his work will be on display at The Heritage Museum in Leadville. He also sells prints of his watercolors at The Heritage and privately.

Given the attention his work has been generating, it’s apparent that Calder’s depictions hold special meaning, not only for those who love his art, but also for those who relish and revere Leadville’s past, and who hope — like the artist himself — to see it preserved.

Lynda La Rocca loves the views from Twin Lakes, where she lives and writes, but she doesn’t try to paint them.