by Charles F. Price

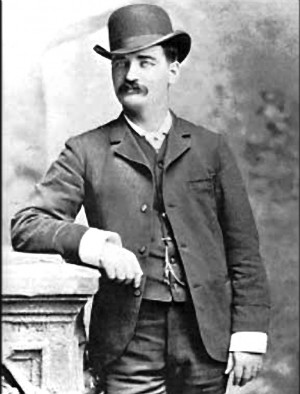

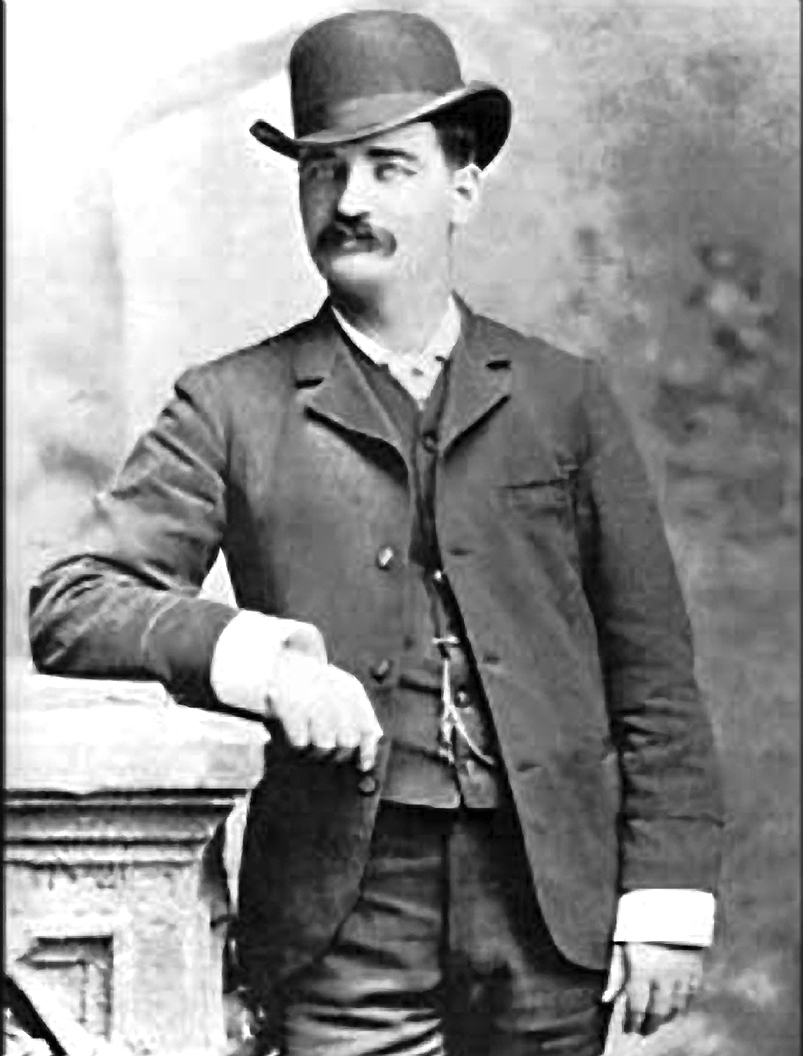

One of the standard histories of Salida, Eleanor Fry’s Salida: The Early Years, asserts that famed Western lawman and gambler W.B. (“Bat”) Masterson once acted, albeit briefly, as town marshal of Salida’s upriver neighbor, Buena Vista.

Wrote Fry, “Town fathers needed to rid the place of ruffians who ran off peace officers as fast as they could be hired. Masterson’s presence, at $30 per week for three weeks, apparently accomplished what local officers couldn’t. It didn’t hurt that Masterson had posters printed warning outlaws he would shoot them on sight.” No source is cited for this assertion and Fry, now in retirement in Pueblo, can only recall gleaning the story from old Salida newspapers.

But she isn’t the only writer to place Bat in Buena Vista enforcing the law. Alfred Henry Lewis, a popular author of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who knew Bat personally, mentioned Masterson’s service there in a 1907 article entitled The Last of the Gunplayers. Lewis, who must have gotten the story from Bat himself, averred, “Mr. Masterson took a man from a mob of lynchers at Buena Vista, and carried him before a magistrate; and … when the magistrate, in sympathetic league with the lynchers, would have committed the man to a local jail, where the mob could get at him, … Masterson tore up the commitment papers in the face of the court, and carried the man off to the Denver jail, where subsequently he was sufficiently yet lawfully hanged.” Bat’s biographer Robert K. DeArment repeats the Lewis account in his book Bat Masterson: The Man and the Legend.

Fry doesn’t tell us exactly when Masterson served as marshal; and Lewis also fails to give us a date, though for reasons presently to be explained, the period late April-early May 1880 seems most likely. The specificity of Fry’s version suggests she was drawing on another, perhaps even firsthand, source. But if, as she told this writer, she consulted old editions of The Mountain Mail, that paper had not yet begun publication in May of 1880, so she must have based the story on retrospective issues of the Mail printed in the mid-1950’s. If she drew from the Chaffee County Times, published in Buena Vista starting in February, 1880, no issues from that period appear to have survived.

Still, the story may well be true. After losing a bitterly contested re-election for sheriff of Ford County, Kansas in 1879, Masterson, according to the Dodge City Times of April 17, 1880, went to “look on the Gunnison country.” Buena Vista, since February 22 when the Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad reached it, had become the natural jumping-off point for mineral-seekers eager to cross the mountains and get at the new strikes around Gunnison. But as late as April 10 the passes were still snowbound and the town was clogged with frustrated would-be prospectors. Had Masterson traveled toward Gunnison on the new DSP&P from Denver, he would have joined this impatient backlog.

There can be little doubt that Buena Vista was the wildest of the wild during this period and was sorely in need of taming. Even one of the town’s boosters, E.R. Emerson, writing for O.L. Baskin’s History of the Arkansas Valley Colorado in May 1881, confessed that the town had till recently been “the headquarters of gamblers, bunko men, and desperadoes, who put in jeopardy both life and property, and by reason of which it gained an unenviable reputation abroad that hindered its growth, while those resident here suffered from the actions of a lawless minority.”

Emerson palliated this dark picture with an assurance that “a different class of people hold sway here now, and Buena Vista has become a prosperous, quiet town …” He doesn’t explain the reasons for the town’s transition from such disorders to the tranquility he describes in 1881. But if there was in fact a lapse in the violence at the time Emerson wrote, it is enticing to believe that the renowned Masterson might have had a hand in bringing the law to the tough new town on Cottonwood Creek. But can we believe it?

Buena Vista was not only end-of-track for the DSP&P and base camp for railroad workers extending the combined DSP&P and Denver & Rio Grande lines toward Leadville, it also held that crowd of frustrated prospectors eager to cash in on Gunnison silver and gold. Inevitably, such a population drew hordes of desperadoes and confidence men – “bunko steerers” in frontier argot – who preyed on such easy victims. Lawlessness was routine. Indeed, one traveler passing through town in late April described it as “the safest place in Colorado for thieves and their allies the bunkoes.”

DeArment contends Masterson went on to Leadville at this time, and indeed he could have done so, since the Barlow & Sanderson stage line made eight trips a day each way in six rough-riding hours. But at some point he must have returned to Buena Vista and gotten over Cottonwood Pass, for he wrote the Dodge City Times in late May that “the Gunnison is the worst fraud (he) ever saw.”

But between mid-April, when he likely arrived in Buena Vista, and the last week in May, when he wrote the Times after visiting Gunnison, Masterson would have had at least three weeks during which he might have served Buena Vista as a peace officer. In fact, an item appearing on May 4, 1880 in the Ford County Globe, another Dodge City paper, seems to verify that he was indeed in town then and did take some sort of action: “A report reached (here) yesterday from Colorado that Ex-Sheriff W.B. Masterson had made a big commotion up about Buna [sic] Vista by a dexterous use of his revolver. As the report has not been confirmed we can give no particulars.” Whatever he did or did not do in Buena Vista, Masterson was back in Dodge City by June 1.

The date of the Globe article is significant – it coincides with that of a particularly violent incident in the early history of Buena Vista. A dispatch in the May 1 edition of the Leadville Weekly Herald reads: “A…Buena Vista special (report) to-day, says policeman Tom Perkins, while making the arrest of bunko steerers, was fatally shot by them.”

In its next edition the Herald ran a bulletin sent from Buena Vista which provided the sequel to Perkins’ death. “This city has, ever since the shooting of an officer by one of the gang of bunko steerers which seems to have taken possession of the town, been in a state of chronic uneasiness, owing to the threats that have been openly made by the murderer’s companions. The murderer has, until within a day or two, been permitted to walk about the streets without let or hindrance, but the indignation of the citizens reached such a pitch that the authorities were compelled to lock him up. Ever since his incarceration the bunko bravoes have openly hinted at rescue, and this morning left town in a body, and in a very mysterious manner. Their movements were considered suspicious, and as indicative of concerted action to carry out their threats, and this afternoon a meeting of citizens was held to consider the best means of protecting the city and securing the safe keeping of the murderer. An organization was perfected, and the prisoner taken from the jail and put on the seven o’clock train for Denver, with a guard of ten men, all well armed. If any attempt is made by the bunkoes [sic] at creating a disturbance, they will find that the law-abiding citizens of Buena Vista know how to take care of themselves.”

In this incident one can perhaps hear an echo of Lewis’s account of Bat outsmarting a Buena Vista lynch mob. If this was the occasion Lewis referred to, he may have inflated Masterson’s role into a leading one when perhaps Bat only acted as a member of the citizens’ group that collectively took action to spirit the killer out of town. Or it may be that Masterson, an experienced officer, was a leader in “perfecting” the organization of the citizenry and directing their subsequent arrest and deportation of the murderer.

The shooting of Perkins seems to have occurred on April 27; the arrest of the killer, William H. Canty, about May 3; and his forcible transfer to Denver by railroad on May 5. Assuming the Dodge City item is factual, Bat’s “dexterous use of his revolver” would have occurred on May 2 or 3, possibly on the very day of Canty’s arrest. Did Masterson arrest Perkins’ slayer at gunpoint virtually single-handed and in the face of a possible jail delivery by bunko men? This version is not quite the same as in Lewis’ account, but the two stories do share interesting similarities.

(In Part Two of this article, appearing next month, the author delves into old records seeking proof of Masterson’s service and reveals fascinating details about Buena Vista’s lawless beginnings.)

NOTE: The author is deeply indebted to Town Clerk Diane Spomer for making available copies of the minutes of the Buena Vista Board of Trustees for the year 1880, and to Town Water Clerk Patti Perez. He is also beholden to Wendy Oliver of the Buena Vista Heritage Museum, who helped locate information about the killer of Policeman Perkins and who, together with local historian Suzy Kelly, aided in the search for those early issues of the Chaffee County Times (Suzy remembers old-timers saying Masterson actually was in Buena Vista). Thanks also go to Assistant Director Kathy Perry of the Buena Vista Chamber of Commerce and to retired author and journalist Eleanor Fry of Pueblo and historian James E. Perkins of Pueblo West.

Charles F. Price is a novelist and historian living in the mountains of Western North Carolina who wishes he lived in Central Colorado. His work has appeared in this magazine on several occasions. He asks anyone who has access to the February-May 1880 issues of the Chaffee County Times to contact him at charlesfprice@aol.com.

I have some comprehensive answers for the writer Charles Price – about what happened in Buena Vista; town marshal; lus names of the leading bunco men and where they went from Colorado.