Column by John Mattingly

Agriculture – July 2008 – Colorado Central Magazine

BAD CREDIT

When I started farming in 1968, the strategy for buying my first farm involved saving the money, and paying for the farm. Same way with machinery. Cash on the barrelhead. If a farmer approached another farmer who had ground for sale, or walked into an implement dealership asking for credit, chances were that farmer left with nothing but a slightly diminished reputation. In those days, in that community, borrowing betrayed one’s inadequacy, and certainly was not considered clever.

Occasionally, say for a large purchase of cattle, a farmer-feeder might call a banker to cover a purchase for a short time until the sugar beet check arrived. There were two banks in the town near my farm, a town with a population of about 25,000. As a footnote, I recall diesel fuel delivered to my farm bulk tank for 11 cents a gallon.

In 2008, perhaps the last year I’ll be involved in farming, farmland purchases almost always involve a lender, and the size of the mortgage payment figures prominently in the transaction. Most machinery is financed, often 100% with 0% interest. Most farmers borrow heavily to operate, and credit management is considered a feature of good business. There are 11 banks in the town near my farm, a town of about 10,000. Diesel delivered recently to my bulk tank cost $4.12 a gallon.

Contrasting the architecture of transactions in 1968 with those of 2008, a key difference is the amount of credit near the foundation. In forty years, we have gone from a largely cash transaction base to one deeply reliant on credit, from a consumer focused on The Price, to a consumer focused on The Payment. I propose that the underlying reason for this shift is tied directly to the increase in the cost of energy, as reflected in the increase in the cost of diesel.

While it’s true we went off the gold standard in 1973, the USSR fell in the 1980s leaving the U.S. atop the world; computers and the Internet changed the shape of the economy in the ’90s; and the New Millennium began in fear. All of these events eventually factor back to the price of energy.

IN THE FALL OF 1973, OPEC (Organization of Oil Producing and Exporting Countries) engineered the first great Oil Embargo. Crude oil at Texas ports jumped from $1 – $2 a barrel to $10 – $12 a barrel. This caused a huge disturbance in the world’s economy, as the cost of energy, formerly negligible, became sizable. Everyone, everywhere, and everything consumes energy, and when the cost of energy increases, the cost of living goes up. What we call “food,” for example, has huge energy components, from the excavators that dug the ore that became the tractor that planted the seeds, to the hydrocarbons that fertilized the growing plants and kept them free of weeds and bugs, to the truck that hauled the harvest to the store that paid clerks to stock and bag it.

The second great Oil Embargo hit in 1978, and oil climbed from roughly $12 a barrel to $40, resulting in the largest peacetime transfer of wealth in world history. President Jimmy Carter understood that the increase in the cost of energy required conservation, restraint, development of alternative energy sources, and ultimately a downsizing of the American standard of living. By executive order, the national speed limit dropped to 55 miles per hour. Carter appeared at news conferences in a sweater, encouraging us to turn down our thermostats. He walked around Washington instead of driving.

But Americans didn’t want to hear this message, especially the part about making downward adjustments in our standard of living. The American business ethic contained a mandate for growth and super-sizing rather than downsizing. The only way to maintain this ethic in the Brave New World of higher energy costs was to borrow back from OPEC the money we were paying them for their oil, a strategy encouraged by the “feel good” Reagan administration. What was good for the Big Goose looked good to the goslings. The mainstream economy in the U.S. came to mirror what was happening internationally.

While Reagan’s administration was essentially borrowing from OPEC (petro dollars) to fund a military build-up to intimidate the USSR, everyday Americans went on a borrowing spree which is only now beginning to unspool. Credit proliferated in the 1980s, changing consumers from owners to owe-ners, or ow’ners for short. With credit cards, creative financing, and a growing host of credit-driven products, consumers could maintain the appearance of growth and super-sizing if, instead of paying for an item, they simply owed on it.

CREDIT CARDs were fairly scarce before 1970, held only by a privileged few. If you had an American Express Card in 1968, for example, it meant you were rich, because the card offered unsecured credit to the holder, so banks issued them only to those with hefty financial statements. But by the late 1970s, credit cards and credit in general were becoming more prevalent. Credit cards played a helpful role in de-marginalizing many people hit hard by the first Oil Embargo.

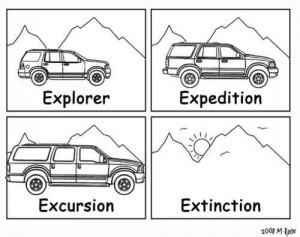

But the second embargo caused an even larger disturbance in the global cost of living, and with Reagan’s election, the United States embarked on a happy-go-crazy path of increasing the availability of credit as a way of preserving the illusion of a growth-based, super-sizing economy. Instead of fuel-efficient vehicles and expanded public transport systems, we came up with 0% financing for SUVs. Instead of developing solar and alternative energies and high density housing with efficient infrastructure, we cookie-cuttered highly leveraged suburbias over millions of acres of farmland. Instead of increasing productivity and capital formation, Wall Street engaged in leveraged buyouts. And, recall that one of Reagan’s first moves as president was to de-regulate the Savings and Loans and loosen regulatory standards on all financial institutions.

I recall friends who told me about the latest game in town in the early ’80s: buy a savings and loan, make loans to yourself and your friends, default on the loans, and collect double from the Federal Deposit Insurance Company. The financial games played at the institutional level in the ’80s (junk bonds, leveraged buyouts, insider trading schemes), together with the proliferation of credit instruments, distracted many people, including farmers, from the fact that monetary inflation masked value deflation. Starting in about 1982, the rapid inflation of the late ’70s and early ’80s resulted in a sudden increase in the price of farms while the net annual income from those farms actually declined. When this dynamic reached a tipping point, lending institutions all over the U.S. were flooded with foreclosure “opportunities” and deeds-in-lieu-of-foreclosure (a farmer or rancher walking into the bank and simply handing over a Quit Claim deed to the farm with keys to the house and gates).

LENDING INSTITUTIONS, of course, didn’t want to get into the actual farming business, and this created an opening for a most interesting financial scheme that became popular in the mid-’80s. Using round numbers for convenience, meet Farmer Fred, who owes The Bank a million dollars on his farm even though the fair market value is only half a million. (A common situation at the time, as banks often lent farmers into insolvency, betting on a horse that never even placed.) Fred sits down with his banker and says he can pay off the million dollar loan if only The Bank will lend him two million. Even as the banker is laughing, Fred says, “But understand, none of the $2 million will leave The Bank. One million of the new loan will pay off the old loan, and the second million will purchase Treasury Bonds yielding 12% in the face amount of $2 million. I’ll assign the bonds to The Bank and you now have a pre-paid principal loan on the books, and in only 5 years, the bonds will be worth $2 million, no question about it.”

(This is the same principle as when you buy a $50 saving bond for $25, only in the ’80s, because bond yields were so high, the time required for the bond to mature at full face value was relatively short.)

The Bank loves Fred’s offer because it purges their books of a delinquent loan, gives them a platinum repayment plan on the principal portion of the $2 million loan, and perhaps most importantly, keeps them from having to jump on a tractor. Fred is happy because he now has his farm back, though he still owes the bank interest on the $2 million for the 5 years it will take the bonds to mature. But, because Fred has handed the bank a pre-paid, gold-plated loan, he gets a real break on the interest rate. The $2 million loan is written at The Bank’s index, which is 7%, or, on $2 million, $140,000 a year for 5 years.

Fred now goes to Another Bank and gets a loan commitment for half a million, secured by his farm, once it is released by The Bank. Fred then returns to The Bank and says, “If I put $500,000 into 5 jumbo CDs yielding 9% in The Bank, and assign the CDs and their earnings to The Bank, will you release the trust deed you hold on my farm?”

The Bank calculates that the $500,000 left on deposit in The Bank for 5 years creates a sinking fund with a number stream that nearly matches the annual $140,000 interest payments on the $2 million pre-paid principal loan. The Bank agrees, glad to be free of Fred at last, and he of them, and Fred now owes $500,000 on his farm to Another Bank instead of a million to The Bank, and he can handle the payments on the half million.

A short, quick version of this scheme often worked in the late ’70s and early ’80s before people understood the significance of the time value of money and the nature of internal, sinking fund arbitrages. Say a farm was free and clear and for sale for $1 million. The buyer writes a contract at the asking price and gets the seller to agree to finance 80% of the purchase price with the condition that the buyer can substitute superior collateral for the owner-financed note.

THE BUYER then goes out and buys U.S. treasuries that match the term of the owner-financed note, but buys them at 40 or 50 cents on the dollar. The buyer offers these U.S. bonds as substitute collateral, and the seller must accept them in lieu of the seller’s own note because it is, in fact, a higher grade of collateral. The buyer thus buys the farm for about a 40% discount.

By the ’90s, creative financing schemes were going wild, and almost everyone had a credit card or two or ten. Even the relatively small players had a hay-day. One of my neighbors got a credit card in the mid-1990s and worked the credit limit up to $18,000, mostly by not paying on time and making only the minimum payment. He then used the card to buy $18,000 worth of livestock, went back to the bank that issued the credit card and borrowed $16,000 against the livestock, which he used to buy a new truck. “It’s like minting money,” he told me. He then used the interest free balance transfer offers of competing Credit Card Companies to defer payment on the $18,000 for 3 years, by which time he’d sold over $50,000 worth of livestock from that initial unsecured $18,000 credit card loan.

In 2000, I decided to buy a new 3′ x 4′ x 8′ hay baler. I haggled my best deal, arriving at a purchase price of $60,000. I had the money, but when I sat down to settle with the dealer, he said, “Put half down and we’ll carry the balance for 3 years at 0% interest.”

I said, “In that case, if I pay in full, there’s a discount, right?”

“Wrong. You can either give me the $60,000 today, or give me $30,000 today and easy installments of $10,000 over each of the next three years.”

“But that makes no sense,” I argued. “Money has a time value.”

“I know it does, but if you want the last discount, you have to take the credit.”

I TOOK THE CREDIT, but it bothered me. Credit should be an optional facilitator in the purchase of a product, not an inseparable part of the product itself. I called the credit carrier’s customer service number and spoke with numerous folks who, when I asked if I might get a discount for paying off early, informed me that the payoff was the same today as it would be three years from now because it was 0% interest. Frustrated, I went up the supervisor ladder until I spoke to a Regional Accounts Manager. I gave him my loan number and asked if I might buy my own loan, at a discount. He told me that my loan had already been sold to a financial factoring company, but he was kind enough to give the direct number of a high level manager in that entity, who, laughing, told me he’d be happy to sell me my note if it hadn’t already been “stripped” into a sequence of synthetic financial instruments that were already floating in the euromarkets.

It struck me at that moment how much things had changed since I started farming in 1968, when I bought my first baler (though only a 14 x 18) for $1,200 cash. The 2000 baler transaction betrayed the extraordinary lengths we have taken, allowed, encouraged, and enjoyed on the way to avoiding the adjustments we should have made in our standard of living starting back in 1974 when the cost of energy took its first step upward, or at the latest when energy costs took their next big leap in 1978 and Jimmy asked us to drive 55 and put on a sweater. Instead of making those adjustments to our standard of living, our economic culture stimulated an eerie boom substituting credit for real financial capacity and actual capital formation.

Read Toynbee. Historically, there is a short flourish and brief bounty in financial services and creative lending practices prior to the decline, and eventual fall, of a civilization.

John Mattingly is trying to give up farming in the Valley.