Article by Sharon Chickering Moller

Local History – August 2005 – Colorado Central Magazine

When a fellow gets to pondering,

In the twilight hours of life,

With his mind just idly wandering

Through old scenes with memories rife;

Of strange happenings that teased him

In the days of long ago;

Of the many things that pleased him,

In the changing, passing show .

(Frank Vaughn, Leadville newspaperman and poet, 1905)

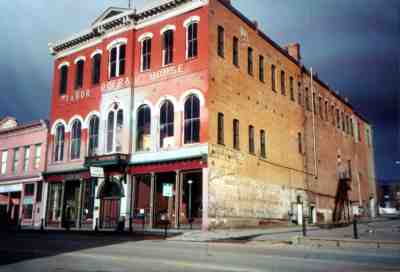

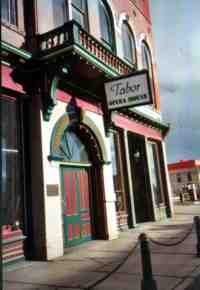

THE RED BRICK WALLS of the Tabor Opera House give few hints of the tragedies and comedies that were enacted within, nor of the equally compelling scenes that played out on the muddy, manure-strewn streets of the 1870s and 80s. Today, pigeons huddle on the windowsills and fire escape of the opera house, and there is little left to indicate the wild, often violent incidents that characterized late 19th century Leadville – where anything could happen, and often did. The streets were a frenzy then, as thousands of prospective miners arrived hoping to strike it rich.

Caught up in the exuberance of the time, storekeeper and future politician, Horace A. W. Tabor, grubstaked two miners who succeeded in April 1878. Flush with money from his one-third interest in their strike, Tabor, along with colleague William H. Bush, couldn’t spend money fast enough, and within months construction of a three story opera house had begun.

Since the first railroad (the Denver & Rio Grande) did not arrive in Leadville until July 1880, all construction materials not already in the city were hauled in by wagon. The grand opening happened one hundred days later, on November 20, 1879, despite the lynching of two men across the street that same morning.

No expense was spared in furnishing the opera house. The newspapers of the time spoke of it in superlatives: “largest and best west of the Mississippi”; “largest and most fashionable audience ever assembled”; “the most perfect place of amusement between Chicago or St. Louis and San Francisco.”

Some of the original Andrews’ folding opera chairs, made of cast iron and scarlet plush (now a little faded), are still installed on the main floor as well as in the balcony. The private boxes near the stage, used by Tabor and his estranged wife Augusta, and their guests, are still there but are now devoid of any lace or curtains which afforded them a measure of privacy.

The opera house was the first building in Leadville to be illuminated with gas (provided, of course, by a company in which Horace Tabor was part owner). Today, two original chandeliers, which have since been converted to electricity, hang just inside the front door. There are no fireplaces in the building, however, since it was heated by a coal furnace.

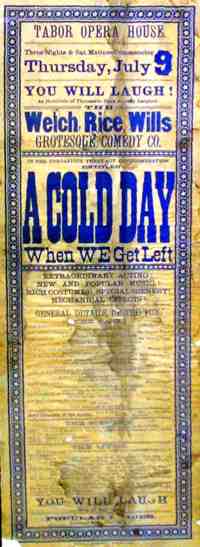

The closet-sized ticket office, with a picture of the beautiful comedic actress, Anna Held, is to the right of the stairs. Theater prices in 1880 were $1.50 for parquet seats, $1.25 for the balcony and 75 cents for seats in the gallery. (Degitz, 1933) Some theaters of that time accepted such items as gold dust, eggs and fresh vegetables in lieu of the entrance charge, so the Tabor may have also. (Cochran)

A broad stairway still leads to the auditorium on the second floor. Lining the stairway are pictures of past performers.

The interior of the theater, a source of great pride, was ornately painted in red, gold, white and sky blue. Oscar Wilde, who visited in 1882 and delivered a lecture from the stage (in a monotone pitched at middle C), may have had a different opinion of the color scheme, for, after his visit he wrote: “I think … you paint your houses in the most horrible colors here in America. In no single house from New York to San Francisco did I see a single piece of wood carving that was worth the name.”(Leadville Daily Herald, 4-14-1882 as cited in: Griswold 1996)

The stage is dark and dusty with long ladders leaning against the brick walls; two sky lights provide a little illumination back stage. An old billboard, tipped on its side, announces a performance of The Unsinkable Molly Brown, and a trap door in the middle allows for disappearing acts.

The House looked old and shabby,

and the scenery was “punk,”

The stage dilapidated,

sorta’ cluttered up with junk,

The drop curtain creased and ragged

and the walls in need of paint

(Don’t think I’m criticizing, for most certainly I ain’t)

(Vaughn)

COILS OF ROPE and extra pulleys lay on the floor, ready to be used. To support the drop curtains, a series of ropes and pulleys attach to the fly loft. The catwalk (or pin rail), 50 to 60 feet above the stage, is “nerve-wracking” but apparently fairly substantial according to Carl Schaefer. Carl was the producer and director of the Crystal Comedy Company, which put on melodramas in the Tabor from 1985 to 1996. They have been the only theater company to offer sustained shows in the opera house, and have performed more times there to more people than any other group.

The Tabor Opera House still owns about ten sets of the original canvas drop curtains and five or six are presently hanging and ready to be dropped into place. One curtain which many people have seen represents Horace Tabor’s optimistic vision for Leadville’s future. Painted in somber colors, the scene is an imaginative look down East 5th Street with Leadville’s old courthouse at the end of the block and skyscrapers rising in the background. Electric light poles with three crossbars each line the sidewalk and hover over adjacent buildings. Additional sets stir the imagination with such elements as courtyards, fountains, formal gardens, and buildings with minarets.

A Chickering upright piano, which has been painted turquoise, sits on the stage. (What would Oscar Wilde have thought of that color?) Later this year a Knabe Piano, originally purchased for the opera house by Tabor, is being returned by the current owner.

To the side of the stage, behind the main curtain, are the knife switches formerly used to control the stage lighting. In this type of electrical system, a metal lever comes into contact with a metal slot. To a novice, it looks like an antiquated fuse box – an electrical nightmare. The knob (insulator) and (ceramic) tube wiring kept the wires separated from other items.

On both sides, in the back, stairs lead down the stone foundation to the dressing rooms under the stage. A wooden box on the faded carpet is marked “Mummy” but filled with the frayed boxing ropes used when John L. Sullivan fought in 1883. Some of the eight or nine cramped, Spartan dressing rooms contain furniture: fainting couch, dressing table with mirror, leather armchair, flimsy shelves, and wooden trunk. The leading man and lady each had his/her own room, with a larger one for choruses.

A newspaper review of the time probably gave a fair assessment of a show:

“When the fact is once taken into consideration that last night was in reality the first rehearsal of the play… amazement will be increased to learn that everything went off smoothly. There were a few tedious waits between acts, and the voice of the prompter was heard on two occasions, but with these exceptions … everything passed off smoothly….”

(Evening Chronicle, 11-19-1879 as cited in Griswold 1996)

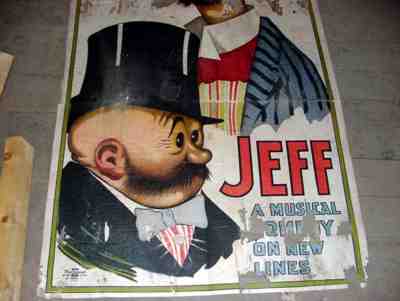

PROBABLY FEW THEATERS today could boast as wide a variety of entertainment as that presented at the Tabor: There was humor, pathos, tragedy, music, dancing, scenic art. (Vaughn). Jack Dempsey, John Phillip Sousa’s band, an alcohol lecture (tickets 50 cents), educated horses, and a séance all appeared on stage. Just recently, while pulling up old linoleum on the third floor, a folder was found with two old posters advertising a musical comedy of Mutt and Jeff. These have been framed and will be displayed.

There was everything from slapstick

to way up high-class work;

Melodrama that was d–n mellow

and tragedy that hurt–

There was some that made you laugh

and some made you tear your shirt.

(Vaughn)

In the first years, performers came to town and stayed several days, but by the mid-1880s when audiences began to decline, and the railroad made it easier for actors to travel, Leadville became part of the Silver Circuit, a booking route between several western cities which brought bigger stars to smaller towns.

At the front part of the second floor was the Tabor suite – five luxuriously furnished rooms which served as an office and private apartments. (Blair)

The third floor had rooms used by the Clarendon Hotel, which was next door. The two buildings were connected by a covered walkway over St. Louis Avenue, between the third floors of each. After being purchased by the Elks, that space was turned into a ballroom. Although probably not by design, the floor is said to “sway” when large numbers of people are dancing on it.

On the ground floor are two retail spaces, at least one of which was often a saloon or bar. One of these spaces, occupied by Sands, Pelton & Co., a Clothing House, rivaled “in beauty and elegance … the finest stores of the kind in Chicago and New York.” This was the first establishment in the city to have a solid glass front (6′ x 11′), presumably hauled in by wagon, unbroken. (Evening Chronicle 11/24/1899 as cited in Griswold 1996.)

In the 1880s and 90s in Leadville, theaters were often above bars, sometimes making it difficult to hear the performers on stage when the imbibers became especially rowdy.

Still visible along the southern wall on the ground floor are a bit of original wall paper and stenciling, as well as a large chalk board used by the Silver Kings in the Leadville Chamber of Commerce and Board of Trade to post daily news, including stock prices. One can imagine the air blue with smoke from the New York Havanas they smoked and hear the cuss words as they discussed business, especially the unfair treatment they felt they were receiving from the railroads.

This house had been the forum

for Leadville’s brains and brawn,

In it we’ve honored those who lived

and mourned for dear ones gone,

In it we’ve voiced our hopes and fears –

our loves and our dislikes –

Have howled our deathless patriotism,

and even voted strikes,

It has echoed our endearments

and we’ve watered it with tears,

And its battered walls are eloquent

with the sentiment of years.

(Vaughn)

The Opera House will continue to be part of Leadville’s history. The current owners, Sharon and Bill Bland, have secured non-profit status for the building, and are soliciting donations from individuals and grant sources for repairs and rehabilitation so the building can again be used for many community functions.

Sharon Chickering Moller writes from Leadville, where she lives.