Letter from Nelson Walker

History – January 2009 – Colorado Central Magazine

Editors:

I enjoyed the articles by Charles Price in the October and November issues of Colorado Central Magazine about the Espinosa brothers. Recently, I wrote Mr. Price to provide him with additional information about the location of the site near Cañon City where Vivian Espinosa was killed. Mr. Price identified the site as being at Grape Spring, which he based on information contained in the biography, Tom Tobin, Frontiersman, written by James Perkins. In my correspondence with Mr. Price I explained that I disagreed with Mr. Perkins assertion that Vivian was killed at Grape Spring, and I presented information that indicated that Espinosa was not killed at Grape Spring, but rather at a place a considerable distance from there, and possibly at a location known as Nash Spring.

Let me begin by providing some background about my interest in this issue. I have lived in Cañon City since 1978, but I didn’t hear about the Espinosa incident until March 2000 when my wife gave me a copy of the Historical Map of Frémont County, Colorado as a birthday present. This map, which was prepared and published by Nancy Calvin Hirleman in 1983, shows the locations of old settlements, schoolhouses, roads and trails, and other features that existed during the early days of Frémont County. One of the features displayed on the map is an “X” with the notation, “Espinosa Killed Here.”

I was very intrigued by the map notation, because I had hiked Espinosa Gulch numerous times but didn’t know the source of its name. I had assumed that it was named after some local miner or rancher, but after seeing the map notation, I was determined to find out who this Espinosa character really was. So I paid a visit to the local history center of the Frémont County Library and asked the librarian if she knew anything about a person by the name of Espinosa. The librarian was very familiar with the Espinosa incident and presented me with several thick files, which consisted mostly of old newspaper and magazine articles. This was the first I had read or heard about the Espinosa exploits, and I was totally captivated by the story. At the same time, I could hardly believe that I had lived in Cañon City for over twenty years without ever hearing about this notorious event.

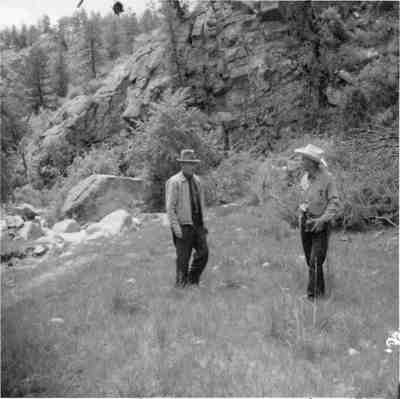

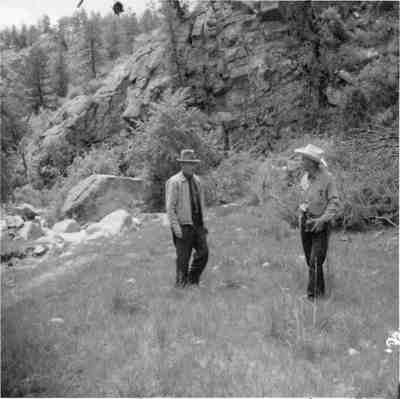

Of the various articles in the Espinosa files, the one that interested me most was a newspaper story from the old Pueblo Star-Journal and Sunday Chieftain, dated March 9, 1969. Besides providing a summary of the murderous attacks and the subsequent manhunts that ended the Espinosa brothers’ lives, the article contains a good quality photograph taken at the supposed site where Vivian Espinosa was shot and killed by Joseph Lamb and Charles Carter. Two men are shown standing in the foreground of the photograph, and are identified as Frank Lamb (Joseph Lamb’s son), and Victor W. Miller (writer for the Pueblo Chieftain and Pueblo Star-Journal). Both can be seen standing in a flat clearing, and there is a tall rock outcrop about fifty feet behind them. According to the article, Frank Lamb had never been to the site until Victor Miller discovered it and invited Frank to visit it.

I obtained photocopies of the newspaper article and photograph with the intention of using the rock in the background of the photo to identify the location of the killing site. The fractures in the rock face were quite distinctive, and I was confident that I could find it.

In addition to the photograph, I had three other pieces of information to help guide me in my search. First, I was already familiar with the location of Espinosa Gulch, as depicted on the Cooper Mountain, Cripple Creek South, and High Park U.S.G.S. 7.5-minute quadrangles. I reckoned that if the gulch was named to commemorate the Espinosa incident, then it was logical to assume that Vivian Espinosa was killed somewhere along the course of this drainage.

Second, I had the Historical Map of Frémont County, which shows the “X” where Vivian was killed. Although a map of this type and scale cannot be relied upon for geographic accuracy, the location of the “X” appears to indicate that the site is situated near the upper end of Espinosa Gulch.

Third, I had several written accounts about the incident that I had acquired from the Frémont County library. All of the accounts stated that the ambush site is located about 20 miles northwest of Cañon City, which corresponds with the site being located in the upper end of Espinosa Gulch. One of the articles, which the librarian told me was from a history book published in 1876, states that Vivian was killed, “…where they were surprised in their camp on High creek, one of the tributaries of Oil Creek.” The name “Oil Creek” was later changed to Fourmile Creek, which is how it is known today.

High Creek is a minor tributary of Fourmile Creek and situated just three miles north of the upper end of Espinosa Gulch. Also, several of the written accounts explain that the posse spotted the Espinosas’ horses in the bottom of a canyon below them. This tidbit of information provided a valuable clue about the nature of the topography where the ambush occurred. It must have been a fairly open area, and the terrain where the posse was traveling could not have been too rugged or steep. Otherwise, it would have been next to impossible for the posse to see the outlaws’ horses from above the rugged and forested portions of the canyon.

With all of this information in hand, a friend and I embarked on the long hike up Espinosa Gulch to find the place where Vivian was killed. As I mentioned earlier, I had hiked the length of Espinosa Gulch several times before, and was well acquainted with the rock formations and the topography that lay along it. I knew that the geology in the low end of the gulch consisted of sedimentary formations, which are primarily dolomitic limestone, sandstone, shale, and conglomerate. On the other hand, the face of the rock shown in the photo did not look at all sedimentary, but displayed fractures that were more typical of the plutonic igneous rocks that are found higher up the drainage.

I also knew that most of the drainage was extremely narrow and surrounded on both sides by steep tree-covered slopes, and that it would not have been possible for any horsemen who were riding the ridges above to see down into the bottom of the gulch. In my mind, the most likely location of the ambush site was near the upper end of the drainage, where the narrow gulch abruptly opens out into an open basin, at the foot of the eastern flanks of the Bare Hills.

On the way up Espinosa Gulch, my friend and I failed to encounter any rock formations that matched the one in the photograph until we neared the upper reaches of the drainage. There we found a tall rock outcrop, exactly like the one in the photo, which also lay near a free-flowing spring. The site is also visible from the high ridges and slopes of the nearby Bare Hills (Big Baldy and Oblong Baldy), from which the posse could have easily spotted the outlaws’ horses from a considerable distance. A few days after hiking to the site I contacted the Bureau of Land Management and ascertained that the spring here is known as Nash Spring.

At this point I felt pretty proud of myself for finding the place where Vivian Espinosa was killed and I really didn’t give it much thought until several months later when I was visiting the old Chinook Bookstore in Colorado Springs and discovered James Perkins’ new biography, Tom Tobin – Frontiersman. I was very excited to find an entire chapter in the book about the Espinosa saga. It was the first detailed and scholarly account of the subject that I had seen, and I could barely wait to get home to begin reading it. Upon reading Mr. Perkins’s account, however, I was dismayed to discover that he had located the ambush site at Grape Spring.

Soon after reading Mr. Perkins’s account I wrote him a letter (December 20, 2000), in which I presented the evidence from the 1969 Pueblo Chieftain newspaper article; including the photograph that indicated that the ambush site was located some four miles upstream from Grape Spring. Mr. Perkins responded to my letter and for the next couple of months we corresponded and talked on the telephone several times; however, I was unable to convince him that his theory about the location of the ambush site deserved further investigation.

As for me, I continue to believe that Mr. Perkins was incorrect in identifying Grape Spring as the site where Vivian Espinosa was killed. In the big scheme of things it probably doesn’t matter one way or the other if he is right or wrong, but for the sake of presenting an accurate picture of this historical event I feel compelled to speak out. Unless historical events are supported by indisputable evidence, then it bothers me that someone is able to establish what people will continue to believe is a fact simply because a book has been published that says it is so. A fact is a fact and a theory is just a theory. When describing historical events I believe that it is vitally important to distinguish between what is fact from what is theory.

The following is a comparison of the theory that Vivian Espinosa was killed at Grape Spring to the theory that he might have been killed 4 miles northwest of here at a place known as Nash Spring.

The Case for Grape Spring

The primary evidence supporting James Perkins assertion that Grape Spring is the site of the Espinosa ambush was the testimony of A.W. Dilley (Deceased), who lived near Grape Spring and told him that Grape Spring was the site of the Espinosa hideout. In addition, in the year 1900 a local resident named Woody Higgens (Deceased) found a rifle near Grape Spring that may have been discarded by Vivian Espinosa’s brother, Felipe.

The Case for Nash Spring

Evidence supporting the Nash Spring theory includes the testimony of three long-time Frémont County residents. All three are local ranchers (two are still living, one is deceased) who are familiar with the Espinosa incident and who testified to me that the ambush occurred at Nash Spring. I cannot divulge their names because I haven’t asked their permission to quote them publicly.

A newspaper story by Victor Miller (Deceased) that was published in the Pueblo Star-Journal and Sunday Chieftain, dated March 9, 1969 provides another source of evidence supporting the Nash Spring scenario. Victor Miller was a rancher and part-time writer who specialized in the history of the old west and wrote numerous non-fictional and fictional stories for newspapers and magazines. He resided on a ranch near Cotopaxi, about 30 miles west of Cañon City. He and his mother established a homestead at Cotopaxi in 1922 and he did much of his writing between 1940 and 1975. Mr. Miller would have had a keen interest in the Espinosa incident and would have had the opportunity to interview local ranchers and residents to locate where the killing of Vivian Espinosa occurred. During the time that Miller was conducting his research there would have been many more people alive who would have known about the Espinosa incident and where it occurred.

This information would have enabled him to guide Frank Lamb (Joseph Lamb’s son) to the site of the ambush. One of the photographs included with the article shows a distinctive rock outcrop that verifies the location of the site. The original photocopies of this article, as well as the original photographs, are located in the Cañon City History Center. Mr. Perkins said that he was not aware of the article until I sent him a copy. A copy of the photo is attached for your inspection.

Further evidence supporting the Nash Spring site includes a letter from Joseph Lamb to Mr. J.A. Israel, dated March 9, 1897, in which Joseph Lamb describes the pursuit by the posse and the eventual shooting of Vivian Espinosa. Joseph Lamb, who was a member of the posse and only 19 years old at the time, made the first shot that hit Vivian Espinosa in the chest. Charles Carter made the second shot that hit Espinosa in the head and instantly killed him.

During the months when I was corresponding with him, James Perkins sent me a photocopy of Joseph Lamb’s letter to J.A. Israel. I had not seen this letter in the library files and I thought that it was odd that Mr. Perkins would share it with me because the descriptions of the posses’ movements that were contained in the letter cast serious doubts on the theory that the ambush was located at Grape Spring. Specifically, according to Lamb’s description the ambush occurred very early in the morning. Shortly after Vivian was killed, his brother Felipe appeared on top of a rock outcrop and fired several shots at the posse before escaping. The posse made a brief pursuit after Felipe, but due to the difficult terrain and the danger posed to the individual posse members of being ambushed themselves or mistakenly shooting at each other, the pursuit was quickly called off by Captain McCannon. Lamb then goes on to explain that the posse spent an hour or two gathering items from the outlaws’ camp before heading for Cañon City.

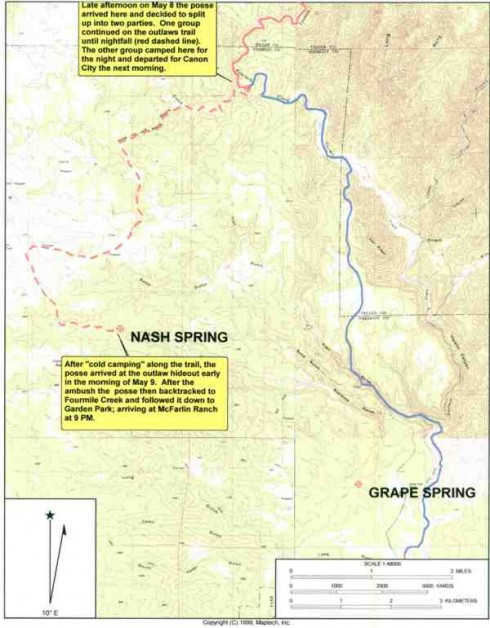

This is the part of Lamb’s testimony that casts doubt on the theory that the ambush occurred at Grape Spring, because according to Lamb’s account the posse did not arrive at Garden Park until 9 o’clock in the evening, where they spent the night at the McFarlin ranch. According to the timeline presented in Lamb’s letter, the posse most likely departed the ambush site around 12 o’clock noon. However, even if the posse didn’t depart the ambush site until 2 or 3 o’clock in the afternoon, they should have easily reached the south end of Garden Park before 9 o’clock. I do not know where the McFarlin ranch was located, but when you consider that the entire length of Garden Park is only about 4 miles long and that Grape Spring is only 2 miles from the north end of the Park, it raises questions about why it took the posse such a long time to ride from the ambush site to the ranch; at most a ride of only 6 miles?

In my opinion, the reason it took the posse between 6 to 9 hours to travel a distance of between 2 to 6 miles is obvious. The ambush didn’t occur at Grape Spring. Assuming that the posse could average 2 miles per hour (a very conservative rate for men on horseback), then the posse should have been able to travel 12 to 18 miles before reaching McFarlin’s ranch. The only reasonable explanation that would account for the 6 to 9 hours of travel time is that Espinosa was killed somewhere else, 10 to 16 miles away from Grape Spring.

The Nash Spring location fits very well with the 6 to 9 hours of travel time that it took the posse to reach McFarlin’s ranch. Although the map distance between Nash Spring and Grape Spring is only 4 miles, it should be understood that this is the straight-line, “as the crow flies” distance. Because of the rugged terrain, it is not possible even today to take horses between the two springs by following a direct route through Espinosa Gulch. Thus, for the posse to ride from Nash Spring to Garden Park would have required a more circuitous route. Under the Nash Spring scenario, the posse would have had to backtrack 7 miles from Nash Spring to Fourmile Creek to the place where they separated the day before from the members of the posse who had gone directly to Canon City with Edgeton. From here they would have traveled another 9 miles via a well-known trail down Fourmile Creek to Garden Park. Thus, the posse would have ridden a total of 16 miles, or 8 hours, to reach the north end of Garden Park. This fits very well with the timeline described in Joseph Lamb’s letter.

To summarize, I cannot say for certain that Vivian Espinosa was killed at Nash Spring anymore than James Perkins can say for sure that he was killed at Grape Spring. Unfortunately, no one is alive who can tell us where the ambush actually occurred. Joseph Lamb’s first-hand account, however, challenges the theory that the ambush took place at Grape Spring, but rather indicates that it occurred a considerable distance from there. Victor Miller located the site at Nash Spring. How did he know that it happened there? A.W. Dilley said that it occurred at Grape Spring. How did he know that it happened there? I interviewed three people who said it occurred at Nash Spring. How did they know that it happened there? In 1900, Woody Higgens found a rusty rifle near Grape Spring thirty-seven years after Vivian Espinosa was killed. Is that proof that the ambush occurred at Grape Spring, or is it possible that this is where his brother, Felipe, carried the gun down the gulch from Nash Spring before he finally discarded it? Who knows? The truth as to where Espinosa was killed may always remain a mystery.

Nelson Walker

Cañon City