Article by Steve Voynick

Mining – July 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

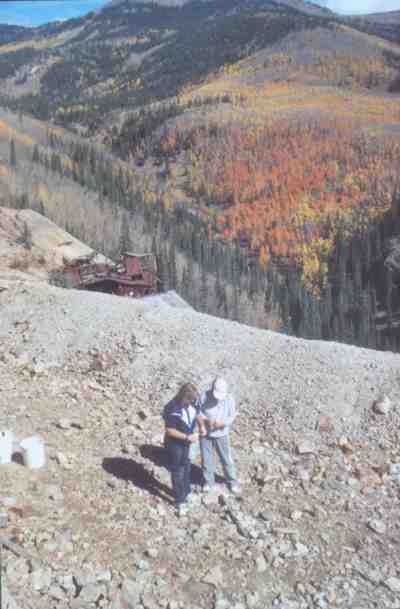

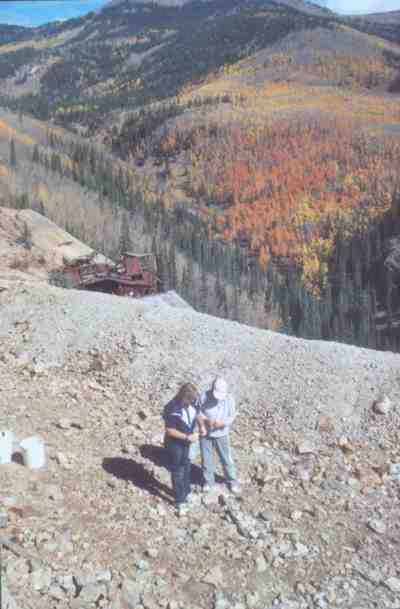

TEN YEARS AGO, time was rapidly running out on the Last Chance Mine. Its glory days as one of Creede’s richest silver mines were long past, and decades of inactivity had left its rutted access road nearly impassable. Perched precariously on a canyon wall high above West Willow Creek, the mine itself was little more than some collapsed portals, a sagging ore bin, a few decrepit cabins, and piles of rock strewn with bleached timbers and rusted cables.

Only a handful of souvenir hunters, mineral collectors, and history buffs even set foot on the mine property. One of those was Jack Morris, a Missouri truck driver who spent his summer vacations in Creede, pursuing an interest in minerals and mining history. Morris’s visits to the Last Chance changed both his life and the fading fortunes of the old silver mine.

“There was something about the Last Chance that just hooked me,” Morris recalls. “It was more than old timbers, rusted metal, and broken rock. What I saw was a dramatic location, a great view, heaps of beautiful ore minerals, and a rich history that was just fading away with each passing year.”

Today, Morris owns the Last Chance. And each summer he welcomes some 600 visitors who enjoy the mountain scenery, photograph the ruins, collect specimens of amethyst-silver ore, and listen to tales of the mine’s history. Some also stay in mine cabins that Morris has restored.

The Last Chance was the site of the last major silver strike in what would turn out to be Colorado’s last big silver-mining district. Colorado’s other silver camps, including Georgetown, Leadville, Aspen, Ouray, and Silverton, were already declining when prospector Nicholas Creede discovered silver in 1889 in an out-of-the-way location in the eastern San Juan Mountains. Creede named his find — an outcropped quartz vein with rich lead-silver mineralization — the Holy Moses Lode. The boomtown of Creede that sprang up nearby was named in his honor.

The following year prospectors made a succession of similar strikes along linear trends that followed long, continuous vein-type deposits. Miners named three of these veins the Solomon-Moses, Mammoth, and Alpha-Corsair. The largest and richest of all was named for its unusual abundance of distinctive purple quartz — the Amethyst Vein.

At the time of the Creede discoveries, mineral exploration was still largely a matter of luck. And that had eluded prospector Theodore Renninger. After fruitlessly searching the rhyolite canyons north of Creede during 1890, Renninger was broke and about to give up. But when Del Norte butchers Ralph Granger and Erick von Buddenbrock offered to grubstake him with $25 and three burros, Renninger decided to give it one more try.

KNOWING THIS would be his last chance to strike it rich, Renninger set out again in August 1891. But things went wrong from the start. First, his burros wandered off, and when he finally caught up with them high on the side of Bachelor Ridge, the stubborn animals refused to move. Frustrated and weary, Renninger decided to prospect right where he was.

This time, luck was with him. Renninger discovered a weathered outcrop of mineralized, amethyst quartz containing a whopping 1,500 troy ounces of silver per ton. He aptly named his strike, which marked the northern end of the Amethyst Vein, the Last Chance.

Renninger then sought the confidential advice of Nicholas Creede, the dean of Creede prospectors. When Creede inspected Renninger’s find, he was stunned by its richness and advised him to register his claims as quietly and as quickly as possible. Creede’s advice proved somewhat self-serving. As soon as Renninger had registered his claims, Creede, wasting no time in actual prospecting, simply staked the adjacent lower ground between Renninger’s strike and the southern part of the Amethyst Vein. Creede’s claims were immediately developed as the Amethyst Mine.

The Creede district shipped its first silver — a modest 380,000 troy ounces — in 1891. But when the Last Chance and Amethyst mines opened the following year, the district’s silver output jumped to 2.4 million troy ounces. By 1893, district production had soared again, this time to 4.8 million troy ounces (about 150 metric tons) worth $6 million.

“By then,” Morris explains, “Ralph Granger, one of the Del Norte butchers who had grubstaked Renninger, had become the sole owner of the Last Chance. In just 18 months, his share of the Last Chance profits had enabled him to buy out the interests of both Renninger and von Buddenbrock for $150,000 in cash. The mine would stay in the Granger family until I bought it more than a century later.”

Ironically, Creede’s emergence as a major silver producer coincided with the silver crash of 1893. With hundreds of western mines flooding the silver market, prices remained strong only because the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 required the U.S. Treasury to purchase silver far in excess of its actual coinage needs. But when Congress bowed to eastern political pressure in 1893 and repealed the act, plummeting silver prices closed western silver mines by the hundreds. The camps most vulnerable to the price collapse were those working lower-grade ores. Leadville was particularly hard-hit because its average ore grade had already dropped below 40 troy ounces of silver per ton.

Although Creede did not entirely escape the effects of the silver-market crash, the extraordinarily high-grade ores in many of its mines more than compensated for the depressed silver prices. Mines like the Last Chance and the Amethyst continued to rack up huge profits on Amethyst Vein ore that averaged several hundred troy ounces of silver per ton.

THE AMETHYST VEIN was a mineralogical wonder, stretching nearly three miles in length, with lower-grade, lead-silver mineralization extending outward 50 feet from its center. The vein’s core was as thick as 15 feet and had a geode-like, concentric structure. Its outermost section consisted of dark quartz rich in lead-silver sulfides, followed by a delicately banded layer of white or bluish agate, another layer of dark, mineralized quartz, and then a layer of amethystine quartz. The latter made up half the total weight of the vein and contained crystals of silver-lead sulfides and green fluorite, along with bits of native silver.

The center of the vein was either hollow or filled with heavy masses of silver-lead sulfides and native silver that graded to 2,000 troy ounces of silver per ton. Many vein sections consisted of composite geodes with multiple cores surrounded by pale-blue, banded, “sowbelly” agate.

At its peak, the Last Chance Mine had 75 employees and a 1,400-foot-long inclined shaft that served 13 underground levels. The mine operated almost continuously under unified management from 1891 until 1947. The Granger family then leased different underground sections to individual teams of miners.

After lease-mining finally ended in the early 1960s, the Last Chance remained idle for ten years. But when silver prices soared during the 1970s, the Granger family hired contractors to “mine” the surface dumps. Some of this dump rock, considered waste by Creede standards of the 1890s, contained as many as 38 troy ounces of silver per ton.

While contractors were mining the dumps, geologists and mining engineers were conducting underground surveys. Despite finding many remaining blocks of high-grade silver mineralization, the steep costs of modern development and environmental compliance precluded any resumption of underground mining.

By the 1970s, the Creede district was nearing the end of the line. After the Commodore, the last of Creede’s original mines, closed in 1976, all remaining district production came solely from the Homestake Mining Company’s Bulldog Mine. The Bulldog had opened in 1969 on silver-lead ore from the newly discovered Bulldog Vein. By the time the Bulldog closed in 1985, Creede’s cumulative district production had topped 50 million troy ounces of silver and 100,000 tons of lead.

THE LAST CHANCE had already been shut down for more than 30 years when Jack Morris came along in 1995. As a professional trucker, Morris had hauled heavy equipment to mines in Missouri’s lead-mining belt and Arizona’s copper-mining belt. Along the way, he developed a strong interest in both mines and minerals. And in Creede, Morris found plenty of both, the most intriguing of which were the Last Chance Mine and its Amethyst Vein ore.

When Morris first encountered the Last Chance, the mine was owned by Nancy Granger Schallen, the granddaughter of Ralph Granger, one of the Del Norte butchers who had grubstaked Theodore Renninger. Over the years, Granger had passed sole ownership of the mine on to his son Paul, who in turn eventually passed it on to his daughter Nancy.

“I introduced myself to Nancy and we talked often about the mine and its history,” Morris recalls. “After awhile, she asked if I wanted to buy the mine. At first I didn’t know what to say. But after thinking it over, I said yes, I did want to buy the mine — but there was no way I could afford it.”

Then Nancy asked Morris what he would do with the mine if he could afford to buy it.

“I told her I’d open it to the public, then compile and preserve its history, sell Amethyst Vein specimens to collectors, and put the proceeds toward restoration,” Morris replied.

Upon hearing that, Nancy Granger Schallen offered to sell the Last Chance to Jack Morris for nothing more than its assessed tax value.

Morris bought the mine in 1997. Three years later he moved to Creede and, together with his wife Kim, began restoring three mine buildings. In 2002, they opened the Last Chance Mine as a fee mineral-collecting site and historic attraction.

Morris charges no admission to the Last Chance. Everyone is welcome to explore and photograph the property and listen to Morris recount the mine’s history. The fee to remove Amethyst Vein specimens from the mine dump is $2 per pound. Collectors usually take home between 10 to 40 pounds, most of it sowbelly agate in small pieces for tumbling and larger pieces for display or cutting. The biggest single piece collected to date was a 300-pound boulder of Amethyst Vein rock for use as a yard display. For those who wish to bring home souvenirs, but not collect them, Morris offers a large selection of attractive specimens for sale.

Along with superb amethyst, native silver, and agate specimens, the Last Chance has also yielded small amounts of turquoise. Along with mines at Leadville, Cripple Creek, Manassas, and Bonanza, it’s one of Colorado’s five turquoise sources.

THE LAST CHANCE provides accommodations for up to 12 guests in restored cabins where water, wood, and bedding are provided. While use of the cabins is free, Morris gratefully accepts donations for his mine-restoration fund.

In the future, Morris plans to open the Nancy Granger Schallen Museum with displays of minerals, mining equipment, and artifacts from the Last Chance and other Creede mines. Morris is also consulting with state mine inspectors about the safety, ventilation, communication, and lighting requirements necessary for approval of public tours on one level of the historic mine.

Located five miles north of Creede on the South Loop of the Bachelor Historic Tour, the Last Chance is open to visitors from Memorial Day weekend until October snowfall sets the closing date.

For further information about the Last Chance Mine, contact Jack and Kim Morris at 719-275-0896 or 719-238-7959, or at 1234 S. 11th St., Canon City CO 81212.

Or check out the website at www.lastchancemine.com.

Steve Voynick, a former miner, has written many books and articles about mining, and lives in Twin Lakes.