WHEN HUMANS EXPERIENCE trauma, a natural response is to avoid the source of it. But, perhaps, if you are an extraordinary individual, you might embrace the trauma for the lessons and silver linings that it can teach.

One cold winter morning in the still-darkness of rural Illinois, then 17 year-old artist, Andy Mast, son of Amish parents, went out to the barn to let his horse out to pasture. When he did not return to the house in a reasonable amount of time, his father went out to find him unconscious atop their mangled metal gate, his horse standing over him.

He doesn’t know for sure what happened, but the horse spooked somehow, unintentionally causing a blow to Mast’s head. Rushed to a hospital, he remained in a coma and experienced two surgeries. His recovery would take over five years.

“The hardest part was not so much the physical as the psychological recovery,” says Mast.

He experienced severe depression, fatigue, weakness and an inability to concentrate. In the early stages Mast could not do much of anything at all. “I merely looked at Western art magazines, hoping to be able to draw again someday.”

Mast had skills in drawing from an early age, “My mother always said I was drawing before I could walk!” Although his family appreciated his skills and deemed them “God-given,” young Amish men are expected to contribute to their communities through the physical work of the farm. So he drew after the chores were finished, late into the evening.

Honing those skills in lantern-lit isolation, as a teen he began to receive random recognition through local art shows. Otherwise, Mast’s work went mostly uncelebrated when he was younger, compounding an often lonely existence of quiet Amish life. But he continued with the self-taught development of his skill.

“It was really a calling,” Mast, now 32, explains about his talent. When his accident prevented him from participating not just in his chores, but in drawing, he descended into depression. “I realized I had to navigate the darkness,” he says, adding that the little bit of light that got through became his beacon of hope. He knew he had to retrain himself to draw. Drawing, for Mast, was not a hobby. It was a need. “Art is who I am.”

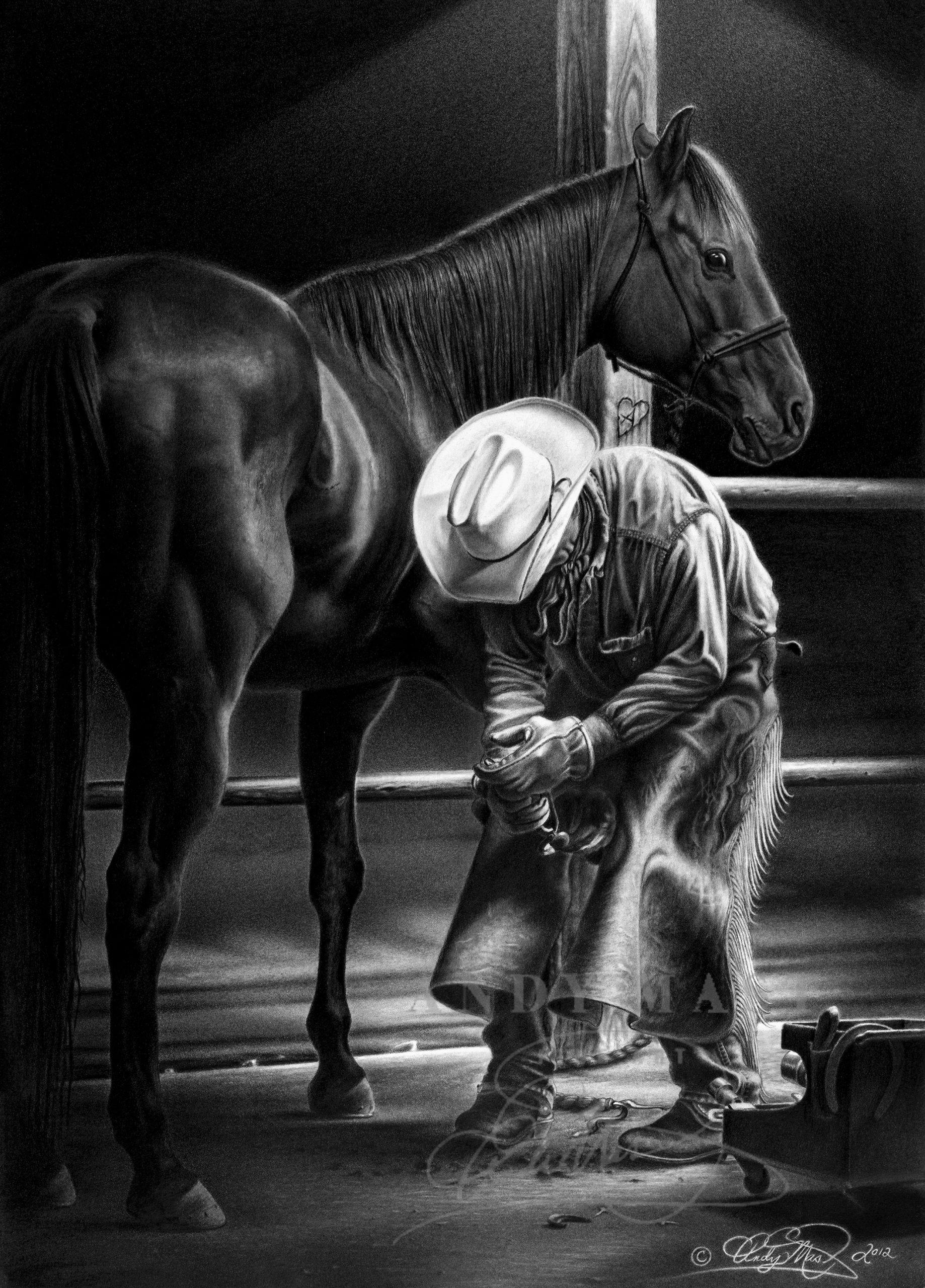

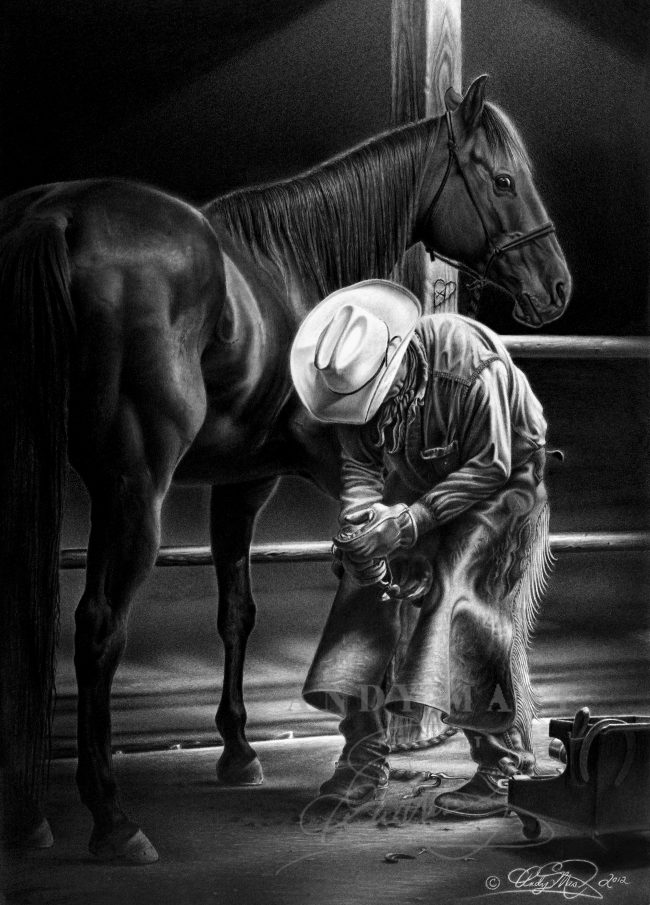

He began, laboriously and, frustratingly at first, mapping out a drawing that became his personal masterpiece, symbolizing his interminable recovery and then eventual success in the art world. It took him two years to complete. “A Long Day,” (pictured on the front cover and in this article) depicts a horse being shoed by a cowboy. He describes the piece on his website: “The minimal amount of light in this piece, I felt so keenly with my own life at that time. For days I would go into the studio in an attempt to work on its progress but lacked the strength, only to collapse in defeat. The cowboy’s posture is stooped and spoke to me of my own debilitation. The dim light beam faintly shining down on the cowboy and his horse matched my own dim ray of hope in life,” explains Mast on his website.

It is the horse in this drawing that represents his mastery over his condition. The horse stands at attention, muscular and alert. His wide eye reflects spirit and determination, which Mast used metaphorically to represent overcoming the darkness and his ensuing recognition that you cannot have light without that darkness. “The happiest people are aware of the darkness, but do not live in it,” he asserts.

This work became a catalyst for Mast’s subsequent success. It won a first prize at the Western Spirit Art Show and Sale at the Old West Museum in Cheyenne Wyoming in 2014, a premier showcase for emerging Western artists. He was just 23 years old at the time. That event helped him to solidify the understanding that drawing was indeed his salvation, his life’s work.

As his health and his art progressed, his works continued to mirror his recovery, reflecting more light, more positivity, less darkness. “It is my hope that my drawings evoke a message of peace and hope to those experiencing difficulties in life.”

When asked about the obvious spotlight in his drawings on, not just farm animals, but to a great extent, the horse, the animal that caused his injury, Mast points out, “I grew up with horses. My life has been wrapped around them. Our family bred horses, and I was always around them. We farmed with them and used them for transportation.” And, he adds, “I know my horse did not intentionally hurt me.”

He is deeply reflective of how, if not for his accident, he might not have experienced the transformation that put the focus on his art. When drawing became the only thing he could do, his family responded with more support than before, grateful for Mast’s healing through his art. They encouraged him to travel when he was able, to the West, where his drawing dreams came alive.

“The appreciation for art culture is very vibrant out west,” he says, pointing to a trip to the Old West Museum in Cheyenne Wyoming, where he received more validation for his subject matter. From there, he came to Colorado to visit Amish friends who had started a community in Westcliffe. “I’ve been here ever since. I find it not only supportive, but inspirational and healing,” he added, “It feels right in Westcliffe.”

He has always been attracted to Western life and the beauty of its traditions. His works pay tribute to a quieter time, showcasing wide open spaces featuring a cowboy and his horse or intimate scenes of a child and dog, the two often gazing at one another with obvious affection.

I met Mast serendipitously while visiting Westcliffe for an entirely different story. I walked into his studio, and there he was, head down, wearing his Amish hat and peacefully working on one of his drawings. The pieces displayed on the wall immediately took my breath away.

As I perused the pieces with more attention, I discovered the focus on the relationships depicted between animals and humans. The two species are represented as equals. Mast agreed that the eyes are one of the most important aspects of the animals he draws, revealing and confirming the existence of their souls.

He was immediately responsive to my curiosity of a young Amish man striking out on an independent, artistic endeavor. “I am so blessed I get to spend my days doing my art,” he responded, saying that, although his family admired his art, they did not always know what to do with it. “They are very supportive of me making a living drawing now.”

Channeling his Amish roots with a quiet positivity, Mast creates bucolic and peaceful drawings with a soft and dreamlike quality in their graphite renderings. But the clarity of the black and white and his microscopic detail create a strength, evoking a magic around the relationships between animals and humans.

The horse is the superhero in his works, both the source of his trauma and his savior. In many ways the humans are incidental, the animals taking the spotlight with intense expressions while the people are depicted from behind or to the side, often shadowed by a cowboy hat. Mast asserts that this is because he is still perfecting his skills in drawing humans, but it seems clear that the animals are his signature subject at this point in time.

Works of art often provide a reflection of their creators. Mast’s drawings are no different — peaceful, kind, approachable and full of humility, yet simultaneously demonstrating his determination and unquestionable focus.

Although he lives in a small town and graphite pencil has not consistently been accepted as a valid Western art medium, his works have been increasingly sought after. The most recent development has been the projection of several of Mast’s pieces onto the iconic May D&F Tower in Denver during the National Western Stock Show this year. He credits a newly hired marketing professional with helping him brand his art and get it out in front of the public more often.

Andy Mast is a true Colorado gem. His art and his story together offer an affirmative sanctuary of strength at a time when finding that is rare. His softly focused renderings provide a temporary shelter, making the observer want to crawl into his drawings and soak up the simplicity, breathe in some clarity.

Similarly, there is a comforting experience to enter the appropriately named, “Grandma’s House” building on the southwest corner of Second and Main streets in Westcliffe. Most often Mast can be found diligently sitting at his desk working over a large pad of paper, pencil in hand, creating his next piece. Like a sage waiting for pilgrims to arrive, he might share some of his modest wisdom. It’ worth the visit!

Mast’s next exhibition will be at the Small Works, Great Wonders, Art Show and Sale at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City in November. You can also view his art at AndyMastFineArt.com.

Jill has lived in Colorado since she was three years old and happily ran barefoot under the strong sun in the vacant fields of her family’s home. She is a freelance journalist.