By Jan MacKell Collins

There is much to say about Colorado ghost towns that have found new life in more recent years. While some places have simply vanished, others have been regenerated in one form or another. One such place is Alpine, located about twelve miles from Nathrop on Highway 162.

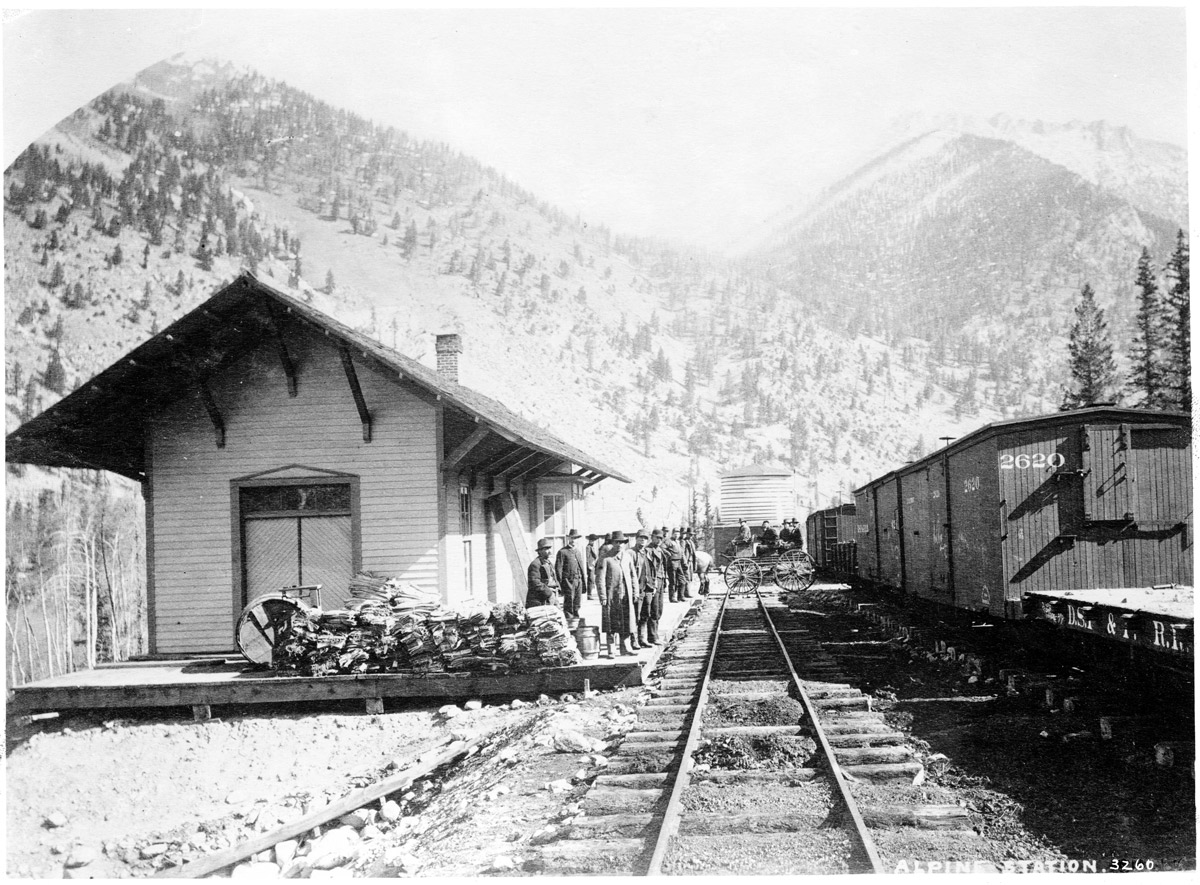

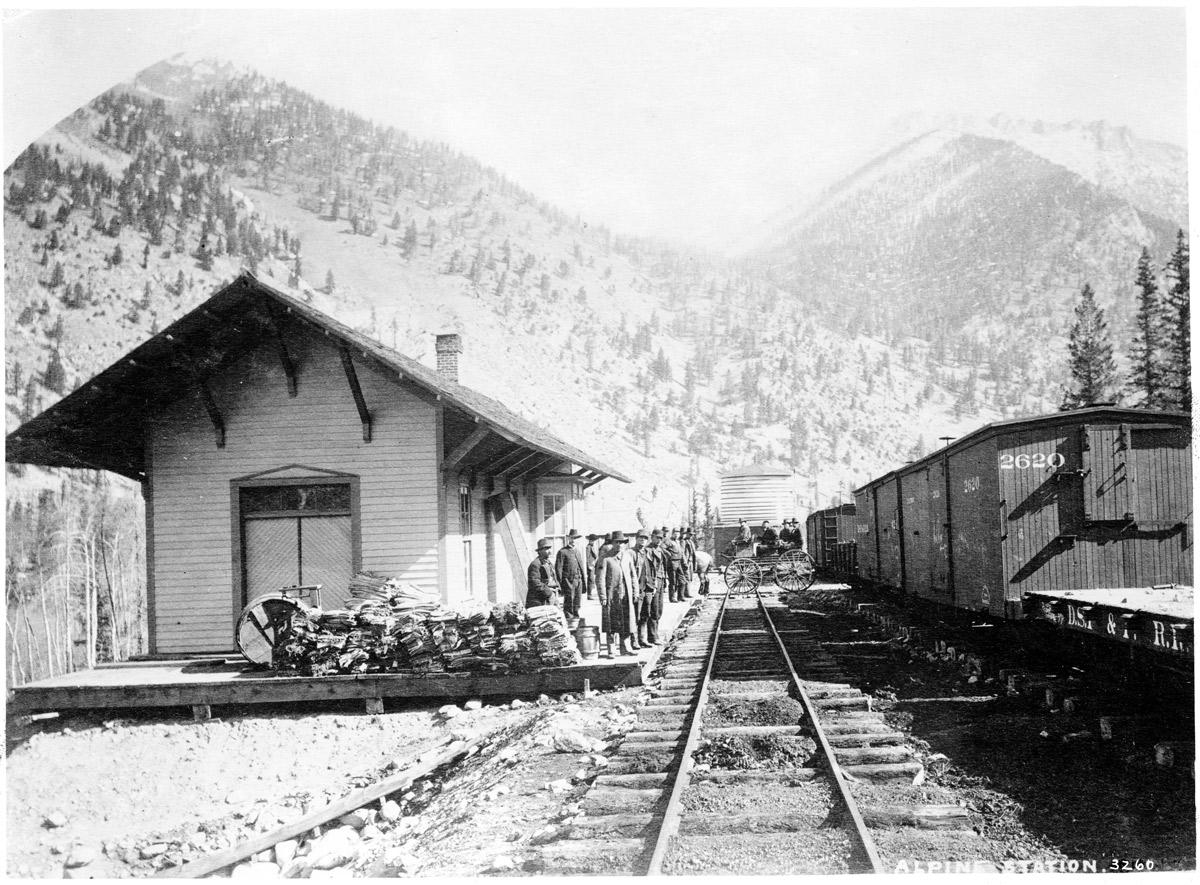

One hundred forty years ago, Alpine began as a supply stop on the Denver, South Park & Pacific Railway. Although the first house was supposedly built in 1877 by B.L. Riggins, Alpine’s post office actually opened in October of 1874. A Colonel Chapman, whose first name appears lost to history, was the first mayor.

Alpine chugged along nicely as a whistlestop on the railroad until May of 1880, when the town incorporated. The area was growing as minerals were discovered. In time the Black Crook, the Britenstein, the Livingston, the Mary Murphy and the Tilden would be amongst the many mines around Alpine. Chapman would soon build the Tilden Smelting & Sampling Works, employing roughly 40 men to process up to 30 tons of ore daily. Alpine’s cemetery had already been established with the death of James W. Couch in January.

Most references to Alpine claim there were over 500 people there during 1880. Locals interviewed during the 1940s put the number at 2,000 or more. Their estimates, however, may have included those who lived outside the city limits, for the actual 1880 census shows only 335 people in Alpine proper.

Most of the men in town were employed in mining. Over a dozen stores, including general merchandise and drugstores, were in business. Bakeries and restaurants fed the people. Several hotels were open, including the Arcade and the Badger. There were at least two barbers, four or more blacksmiths, and several attorneys. A lumberyard sold timber. There was even a real estate office and three banks. A stage company took travelers to nearby St. Elmo and beyond.

Some of Alpine’s residents commuted to work elsewhere, for in 1880 construction began on the Alpine Tunnel a few miles away. The purpose of the tunnel, which was largely financed by Colorado Governor John Evans, was to extend the rails of the Denver, South Park & Pacific to Gunnison. At over 11,500’ in elevation, Alpine Tunnel was no place for the weak. The railroad ended up offering free transportation to any man who came to work on the tunnel. More than 10,000 men took the job over time, but subsequently quit due to the altitude.

Workers at the tunnel were housed in six cabins on the west end, and there was also a settlement called Atlantic on the east end. There is little doubt, however, that at least some of the laborers chose the cozier quarters at Alpine, and history has sometimes confused the town with the tunnel, as well as Alpine Station not far from town. But only Alpine had any real entertainment. There were between two and 23 saloons depending on the source. A two-story dance hall also provided a place for the only two musicians in town to play.

The rough environment at Alpine’s was proven, at least in part, by the shooting of G.W. McIlhany. The census does, however, record Police Judge C.R. Fitch and at least three police officers, including a city marshal. Even so, life at Alpine could be quite gritty; in July, Patrick Dempsey had been dead nearly three months when his body was found in nearby Grizzly Gulch, his head crushed by a boulder.

[InContentAdTwo] Alpine’s rough reputation was furthered by the lack of many churches in town, although the site of at least one house of worship remains. There was also a Sunday school run by one of the ladies in town. Perhaps a dearth of any other proper culture was what inspired the owner of Alpine’s newspaper, the True Fissure, to pick up his printing press and move to St. Elmo.

In 1881 a school was at last provided by George Knox, although the town was yet so wild that it was said Knox declined to bring his own wife and seven children to Alpine. But there were families, as illustrated by the 1880 census, as well as the death of three-year-old Mattie Pitts in 1882. By then, however, St. Elmo was growing so fast that it quickly usurped Alpine as a place of importance.

Folks remained at Alpine longer than most believe. Burials continued at Alpine’s little cemetery, and it was not until 1904 that the post office closed. The Alpine Tunnel collapsed in 1910, killing some men who were overcome by coal smoke. The tunnel was never rebuilt, since several area mines, including the Mary Murphy, were shutting down for good. Alpine’s fate as a ghost town was sealed. Or was it?

Over time, some buildings blew over while others were moved. But at least a few homes remained occupied by itinerants well into the 1920s. Two of them, notably, were Pearline “Princess” Zabriskie and her friend, Napoleon Jones. Zabriskie in particular was interesting because she claimed to be a Polish princess and wrote a paper on the value of molybdenum and uranium in the region.

In reality, according to the 1920 census when both Zabriskie and Jones lived in St. Elmo, “Lady Zabriskie” was born in Nebraska. She also moved around a lot, taking up in empty homes not just at Alpine, but also St. Elmo and other area towns including Romley and Hancock. In 1924 she was found frozen to death and was buried in Salida. Likewise for Jones, who lived mostly at St. Elmo from 1900 until he too died in 1928. His obituary claimed he was the last official resident of Alpine.

When historian Muriel Sibell Wolle visited Alpine in 1949, there were still a few buildings standing, and the area was becoming popular for recreation. People began building summer homes and fixed up some of the remaining buildings. Today it is difficult to discern the old from the new, but the original Alpine remains to an extent. The Alpine cemetery also remains as a testament to the original town, even if the graveyard is located next to a newer home. Of the 39 graves, only a few markers remained as late as 1986 and the grounds may be on private property. Even so, a visit to the area is still worth the trip.

Jan MacKell Collins is smitten with the idea that remembering Colorado history matters.