In 1977, soon after going to work for Ed and Martha at the Middle Park Times in Kremmling, I set out one evening to explore the region. Near dusk, returning from Steamboat Springs, I rounded a curve in the road and smacked into Bambi. The collision shoved the grill into the radiator and put me in a pickle. Close to broke, I caught a ride to Steamboat, where I scrounged my quarters and called Ed. He cheerfully replied that he’d be over the next morning with a few tools. He came, and after a trip to a salvage yard for a new radiator, which he modified and installed, he had me mobile once again.

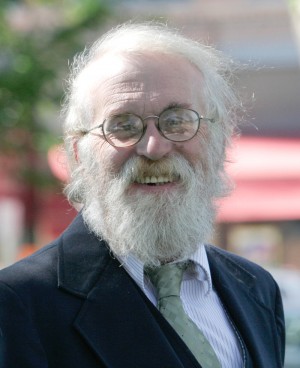

His hands were so inventive. They repaired CompuGraphic typesetting machinery at the Mountain Mail in Salida, brewed beer, and built computers, usually in the interest of frugality and often in a spirit of generosity. They were, in my memory, short and meaty, like you might expect of a mechanic, not the long, slender fingers normally associated with merchants of ideas. That was Ed. He bridged many disparate worlds.

Ed had blue-collar origins, working in the steamy family laundry in Greeley. Throughout his life he saluted the miners, railroaders and sawyers who did things with their hands. He championed wilderness preservation, but in his backcountry rambles that we shared he was most drawn to the residual human record, whether the Pride of the West Mine in Pomeroy Mountain, west of Salida, or the old Midland Railroad tunnels under Hagerman Pass, west of Leadville. Often, he mentioned his experiences with dynamite, a tool of the working man and an element in the early 20th century labor wars in Colorado.

At his core Ed was a geographer and historian. About Colorado, he had vast stores of knowledge in both disciplines. But to truly understand this place required him to analyze a much larger world through time. The Civil War was an absorbing quest, a book on that topic in his hands at the very end. One of his favorite books, I think, was Nature’s Metropolis, Williams Cronin’s study of Chicago’s economic empire. Railroads, highways and water – they all interested him. Far from the universities and skyscrapers, he analyzed the world.

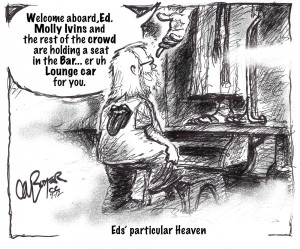

Ed’s writing won him modest fame, and it was a remarkable skill. He could deliver a history lesson, provoke a chortle and a snort of indignation – then take you to a place you’d never expected, all in the space of 600 words. I believe that unpredictability is what set him aside from lesser writers. When he went to work for The Denver Post in the mid-1980s, Chuck Green, then editorial page editor, said he thought Ed could become nationally syndicated within two years. It never happened, but on his best days he was as good as anybody and better than most.

In the early 1990s, I suggested that by relocating to Denver, he could more directly engage in the issues of the urban masses – and perhaps earn a living commensurate with his talents. Too, I thought a dose of city living would curb his sometimes curmudgeonly instincts, which at times overpowered his wit and insight.

Instead of the city, Ed and Martha started Colorado Central Magazine, a paeon (a word I learned from Ed) to a place of small towns and, in its very name, an education. On the day that Ed died, I was returning to metro Denver from a weekend excursion to the Cottonwood Hot Springs. We stopped in Lake George, and I told my companion that this was geographically the center of Colorado. It was a factoid, courtesy of Ed, but as in so many things, it was also the key to a broader understanding of the universe that we shared.

Allen Best is the publisher of Mountain Town News. It provides in-depth analysis of economic, environmental and social trends in resort-based mountain valleys of the West. www.mountaintownnews.net