Essay by Ed Quillen

Energy – September 2008 – Colorado Central Magazine

LAST WINTER, with fuel costs rising, I talked with a writer about some articles focusing on energy in Central Colorado. The plan was abandoned for a variety of reasons, but one big reason was that it seemed almost impossible to draw up an “energy budget” for our region.

That is, how much energy do we produce? How much do we consume? How will rising petroleum prices affect us, and how might we best cope? With a regional economy that relies heavily on auto-based tourism, what happens when potential visitors decide it’s too expensive to drive here?

Start with local energy production. If we still used draft animals like mules and oxen to any significant extent, energy production would include oats and hay.

Those who complain that corn-based ethanol is affecting food production have a point, but it’s not a new issue. If most American farmers still used horses for plowing and harvest, then millions of acres now devoted to other crops would have to be switched from beans or wheat to forage crops like oats. Plus, a farmhand on a tractor can get a lot more done in a day than a farmhand behind a team. I’ll try to talk John Mattingly into addressing this in one of his columns.

When I lived in Kremmling 30-odd years ago, quite a few nearby ranchers still used horses, rather than tractors, to pull the wagons and sleds they used for the winter feeding of cattle. It wasn’t sentiment that kept the horses at work. The horses started every morning, even when it was 40 below zero, and one man could handle both driving the horses and tossing feed. Tractors can be hard to start when it’s cold, and require two men — one to drive the tractor and another to toss the feed. So there are times when draft animals work better, but I’m digressing here.

Back to local energy production. We burn a few cords of local firewood every winter, and so do a lot of people we know. But I don’t know of any way to get solid numbers on this form of local energy production.

Some mountain towns and counties, none that I know of in Central Colorado, are using “biomass” for heating. For instance, Gilpin County (its seat is Central City) has just opened its new road-department shop building, heated by biomass, which is the fashionable term for what we used to call firewood. Local suppliers thin the forests, thereby reducing fire hazard, and sell the wood to the county, which runs it through a chipper and into the boilers.

So far, according to my friend Forrest Whitman who’s a county commissioner there, it’s working pretty well. It provides a market for wood from trees that should be removed, like those choking stands of lodgepole. It keeps money circulating in the community while providing local employment. Less money gets exported to pay for natural gas or propane.

But it still involves imported fossil fuels for chainsaws to fell the trees and pickups to haul the wood.

Margaret and Gene Rush designed their house near Salida to be heated by passive solar energy — big south windows with an overhang designed so that the windows are shaded in the summer and exposed in the winter. They spend next to nothing on heat; her article about it is at link.

BUT DOES THIS COUNT as “energy production” ? Perhaps not. But the effects of home energy conservation can be estimated. Years ago I ventured over the Sawatch Range to Old Snowmass to interview Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute for an article for Country Journal. His home and headquarters contained a central greenhouse, and Lovins had calculated that it was the energy-producing equivalent of a stripper well that produced a third of a barrel of crude oil every day.

Owning a house that’s a net energy producer is an appealing thought, especially with something as simple as passive solar. But our house was built with a coal furnace when coal was about $3 a ton and nobody worried about such things. Retrofitting it to that standard would essentially mean starting over with a bulldozer and a dump truck, but I can’t think of any good reason that our building codes shouldn’t require new construction to use passive solar designs. We get lots of sunshine in Central Colorado and we might as well make the best use of it. Plus, money that isn’t exported to buy propane or natural gas is money that can circulate here.

More conventional forms of local energy production could be quantified, I suppose. It wouldn’t take too much work to get the numbers for the small hydro-electric generating plants along the South Arkansas River above Maysville. Or for the big hydro-electric production from the Bureau or Reclamation’s Aspinall Unit west of Gunnison, whose three dams have a combined capacity of 291 megawatts.

BUT HOW WOULD YOU figure something like the Mt. Elbert Pumped Storage Plant at Twin Lakes? The idea is to pump water uphill in the wee hours, when steam-powered generating plants have to keep running even though electric demand is low. During the day and evening, when electric demand is high, they release the water to spin turbines and generate electricity. Thanks to friction and the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the plant consumes more electricity than it produces, but it adds to the overall efficiency of the electric grid.

Then there are the small private hydro plants, such as the one at the Orient Land Trust, home of Valley View Hot Springs. Wilbur Miller heats and lights his ranch house west of Westcliffe with his own little hydro-electric plant on Hennequin Creek. Up at White Pine, Frank Culbertson used to generate his own electricity from a small creek until he moved on. Doubtless there are many more.

@Normal = We also need to consider geothermal — essentially, hot water from the ground. We’ve got a fair amount of that, as evidenced by various spas from Mt. Princeton to Valley View, the Poncha Hot Springs, the Gator Farm’s well, etc.

Again, however, it’s hard to quantify, especially in regard to effective production. I suppose you could take something like Valley View and compute how many BTUs it uses, and say it produces the equivalent of X amount of natural gas. But without the natural hot water, there wouldn’t be a resort there to need the energy. So can we really call that “production?”

WIND WE HAVE APLENTY, and in my dream world, Salida would be surrounded by turbines so that there was never more than a gentle breeze in town and those awful April gales would light my house. But I don’t know of any production hereabouts, other than a few small units.

Solar electricity, like hydro, comes in a lot of sizes. On the small side, Slim Wolfe has his solar-powered workshop near Villa Grove. Back in 2002, we ran an article (www.coloradocentralmagazine.com/archive/cc2002/01060131. html) by Dan Bishop of Saguache County about how he and his wife live a fairly conventional and comfortable life off the grid with solar power. There are doubtless many more, but for obvious reasons, the production from “off the grid” systems is hard to quantify.

Others would be simpler. The last time I took pages to our proofreaders, Matt and Sally Gonzales on the outskirts of Salida, Sally was delighted to show me her electric meter running backwards on account of new solar panels. And of course, there’s the new 8.2-megawatt solar-panel SunEdison facility in the San Luis Valley.

As for fossil-fuel production, I suppose it depends on where you draw the lines for Central Colorado. Crested Butte was once a coal camp, but hasn’t produced since about 1954. Its coal went to CF&I’s blast furnaces in Pueblo; when the company closed the Big Mine, there wasn’t enough rail traffic remaining to keep Marshall Pass in business, and the rails were torn out in 1956.

Gunnison County still produces a lot of coal, but the mines are over on the North Fork around Paonia, a long ways from our neck of the woods. Frémont County was once a major coal producer, but its last mine closed at the end of 2000.

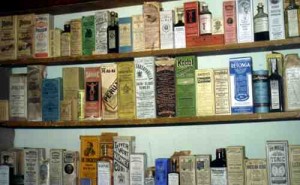

Florence has a long history of oil production. The nation’s first oil field dates back to 1859 in Pennsylvania, and the second was near Florence. The first well there dates to 1862, and soon a primitive refinery produced kerosene, which fetched $6 a gallon after being hauled to Pueblo and Denver by ox team. By 1922, there were dozens of wells, and the Continental Oil Company had a large refinery in Florence that produced a full line of lubricants, as well as gasoline, kerosene and paraffin. There were two smaller refineries as well; all were closed by 1936.

THE FIELD’S PRODUCTION peaked at 824,000 barrels in 1892, but some production remains — 45,155 barrels in 2007, or about as much oil as America consumes every three minutes. Well No. 44, which began pumping in 1882, is the nation’s longest continuously producing oil well.

Alamosa, too, had an oil refinery; it lasted until 1964. But its supply of crude oil was not nearby; it came from the area of Farmington, N.M., nearly two hundred miles away. Narrow-gauge trains hauled the crude oil in tank cars, and this traffic helped preserve the line into the 1960s. These days, there’s a natural-gas boom (or coal-bed methane boom) in the Four Corners area, but that’s a long way from here. And there’s that exploratory drilling for natural gas in the Crestone area.

One trend seems apparent when looking at the history of commercial energy production here — it tends to get more centralized. One big oil refinery in Commerce City has replaced small refineries in Florence and Alamosa. Big power plants replace small ones, which is what happened in Salida (where the old power plant is now home to the Steam Plant Theatre) and in Leadville (where power was once produced in a historic building in California Gulch). There remains the Black Hills Energy coal-powered plant on the west edge of Canon City, with a capacity of 45 megawatts.

On the other hand, we do have dispersed supplies, too, ranging from firewood and geothermal to small hydro and home solar, representing a long and noble American tradition of tinkering toward self-sufficiency.

As you can see, there are a lot of ways to produce useful energy, but I don’t know of any good way to quantify them in order to get a remotely accurate number for our energy production.

Some things, like electric generation, obviously count. But I recall a conversation with George Whitten, Jr., who ranches in Saguache County. “Basically, we use grass to capture sunshine,” he said. But is that energy production or food production?

Today, with bio-methane and biomass energy resources currently under consideration in many communties, has such a distinction become artificial?