Sidebar by Martha Quillen

History – April 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

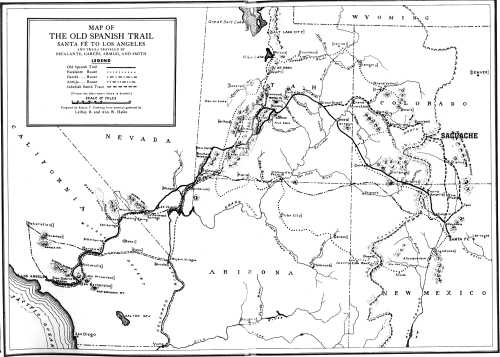

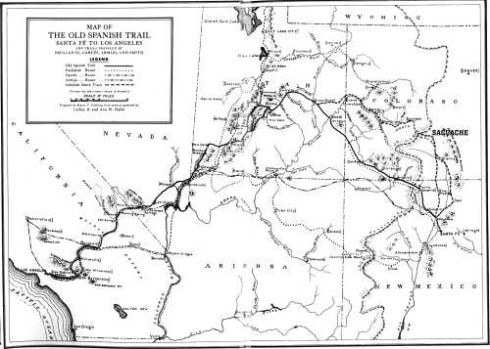

Long before San Luis, Alamosa, Moffat, Saguache, and Gunnison were founded, trappers, traders, and merchants came through this region ferrying goods from Santa Fe to southern California — and back.

The Old Spanish Trail evolved slowly as priests, fur trappers, slave traders, explorers, and New Mexicans headed west. The Eastern end of the trail developed in the 1700s, but the first recorded expedition to Los Angeles didn’t happen until 1829, when Antonio Armijo left the village of Abiquiu with 31 men in order to find a route to California. A preliminary report written upon his return concluded: “It is hoped that in other trips a shorter road may be discovered….”

Due to frequent violent encounters between travelers and natives in what would one day become Arizona — and poor forage, overheated deserts, and yawning canyons to the west — travelers bound for el Pueblo de los Angeles in the 1830s usually headed north out of Santa Fe, journeying to the village of Abiquiu then up into the Four Corners area.

Some travelers went due north, however, establishing routes on both sides of the Rio Grande; one roadway swung into Taos, the other went through Tres Piedres. Both branches crossed into the San Luis Valley, where they joined and turned west into what’s now known as the Gunnison Country.

The Old Spanish Trail was a formidable 1200 miles long — plus or minus several hundred miles since it included numerous alternate branches along its lengthy course. Travelers set upon different paths, depending upon who they were, where they were coming from, what sort of load they carried, what kind of pack animals they had, what season it was, rumors of Indians, and prevalence of grass and game.

Despite its circuitous route, the trail became well-established in the 1830s, serving merchants, trading companies, settlers, and a veritable who’s who of famed mountain men. Traders typically took pelts, serapes, and hand-woven woolen blankets to California, and herded back mules and horses, which were raised in abundance on the lush grass in temperate California.

But after the Mexican War the trail fell into disuse. The last large Mexican mule train left California in the spring of 1848. Soon afterwards, the Americans, ever enthusiastic about westward expansion, built forts and sent out soldiers to protect travelers. Before long, more serviceable wagon roads developed, and other routes eclipsed the Old Spanish Trail.

During the next century, the Santa Fe, Oregon, and California Trails were remembered and visited, but The Old Spanish Trail was largely forgotten. It had, after all, been short-lived. But wrapped into its history was the story of Old Mexico and New Mexico, early explorers, fur trappers, mountain men, and settling the Western interior.

Finally interest in researching and exploring the trail increased — and prevailed. Since 2002, the Old Spanish Trail has enjoyed official historic recognition.

Chapters of the Old Spanish Trail Association worked hard to gain recognition for the trail, and are now working to preserve and publicize the trail, and to collect history and lore regarding its use. Today, the government is working on a comprehensive management plan, and an old-fashioned 100-mile trail ride is an annual attraction.

Martha Quillen