Article by Ray Schoch

Drought – May 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

REVELATION

I came to Colorado after half a century in St. Louis, Missouri — where 40 inches of rain a year, the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi, and oh, yes humidity rivaling a Brazilian rain forest’s, made for a water supply which seldom entered my thoughts. I was retracing the Oregon Trail for the first time in 1975. Standing on top of Scott’s Bluff that June, looking west to the Laramie Range on the horizon, it dawned on me that, despite the bright Nebraska sun and a temperature of 85 degrees, I was comfortable. All those “but it’s a dry heat” jokes suddenly made sense.

Decades later, I retired, and hoping to stabilize my housing costs after a few years of renting in suburban Denver, I became the ambivalent owner of a tiny house in “old town” Loveland. Platted in 1922, according to Larimer County records, my lot is 50 x 150 feet, and at 7,500 square feet it’s smaller than the floor area of a good many Colorado McMansions. My modest abode is set back nearly 100 feet from the street, and faces directly south. Originally built in 1945 as a cabin near the shore of Lake Loveland, it was expanded in 1982 to a palatial 856 square feet. Fortunately, the builders of the cabin surrounded the place with cottonwoods in 1945, and the shade of those now-mature trees makes even hot summer afternoons reasonably comfortable.

Numerous Colorado vacations before I became a resident had introduced me to prairie grasses, shrubs and western wildflowers, which seemed then — and still seem to me now — both exotic and quite beautiful. Once the home purchase was complete, and before the current drought was getting publicity, I’d already decided I wanted something different for landscaping. Prairie appealed to me, and a natural way to recreate that prairie seemed obvious — xeriscape my front yard.

MOTIVATION

My motivation was threefold. First, it simply made sense to use plants that grew here as natives, or plants that would adapt to this climate without much help. I’m neither a compulsive nor an expert gardener, and fussing over a new plant through half a dozen growing seasons is simply more trouble than I want to go to.

Second, the idea and the reality of a “short-grass prairie” or a meadow of Buffalo and Grama grass, seasoned with some Little Bluestem or other bunch grasses, decorated with a generous helping of spring wildflowers and native shrubs, is very appealing to me. Part of that appeal is a labor-saving one. Once established, a meadow might not have to be mowed. This would simultaneously save me work and allow me to get rid of my noisy and obnoxious power mower.

Third, as a retired teacher on a fixed income, I felt sure that my budget would appreciate lower water bills. Fortunately, “old town” Loveland has no homeowners association to make Highlands Ranch-type rules requiring particular house colors, or the wasting of water on lawns during a drought.

A review of my water bills from the City of Loveland over the 24 months I’ve lived here reinforces that last point. I already knew I could reduce both water usage and frequency of mowing by setting the mower to cut the grass as high as possible. My water usage has been quite stable except for the summer growing season. In 2001, still tied to St. Louis habits, I watered the lawn frequently, and mowed it probably half a dozen times from May through September. Water usage rose to a peak of 11,000 gallons in July, and total lawn water usage for the May-September season was 16,000 gallons. Last summer, as I began to implement my plans while Loveland imposed lawn watering restrictions, I watered the lawn only three times. Lawn water usage for the 2002 May-September season was 7,000 gallons, or less than half that of the previous year. If nothing else, these numbers reinforce complaints from upstream Coloradans that an awful lot of municipal water is being used to keep Front Range lawns green.

I not only reduced the amount of watering, I watered differently. Instead of the routine that many automatic sprinkler systems follow — 10 to 20 minutes of watering every day that regulations allow — I decided to do only in-depth watering, applying an inch of water to a given area before moving my “hose-end irrigation device” (sprinkler) to a different spot. According to the sprinkler label, its maximum flow was ½ inch per hour, so I let the sprinkler soak a given area for two hours before moving it to a different part of the yard, and I was careful not to water the sidewalk.

I only watered the yard once in July, once in August, and once in September, and that watering was more for the benefit of the Cottonwoods than the grass. At summer’s end, most of my yard was as green as that of my neighbor to the west, whose underground sprinkling system applied 15 minutes of water to his lawn on every day allowed by the city’s watering schedule. The exception which makes it most of my yard and not all is the 15 feet or so closest to the street, which bakes in the sun all day, and was bare dirt by August.

WHERE TO START?

Perhaps the operative question for people like me, who haven’t been lifelong gardeners, is “Where to begin?”

The answer seems to be: read — and ask questions.

My sister, a 25-year resident of the foothills west of Denver, provided some introductory information. Her middle daughter, an avid gardener who’s taken several classes at the Denver Botanical Garden, added more advice and encouragement. I made trips to the Denver Botanical Garden myself, hounded a few of their employees with questions (always cheerfully answered), took copious notes, and purchased several books specifically about xeriscaping. Sunset Books Western Garden Book and Western Landscape Book have useful information. Lauren Springer’s The Undaunted Garden and Passionate Gardening are, well, passionate in advocating native and water-wise plants and gardens, though lacking in the step-by-step specifics a fledgling gardener would find useful.

Denver Water and Fulcrum Publishing in Golden share the credit for a trio of slender but attractive and useful volumes on both the philosophy and practicality of xeriscaping, including recommendations for specific plants and plant types — Xeriscape Plant Guide, Xeriscape Color Guide, and Gayle Weinstein’s Xeriscape Handbook. All three are well worth the money. Finally, I’ve also found The Xeriscape Flower Gardener: A Waterwise Guide for the Rocky Mountain Region, by Jim Knopf, published by Johnson Books in Boulder, to be useful.

To my great good fortune, I live only a few miles from two excellent nurseries in Fort Collins that have native or xeric sections of their plant display yards stocked with flowers and shrubs and grasses that are native, or that have adapted well to the local climate and soils. Fort Collins Nursery and Gulley Greenhouse employees have been helpful and enthusiastic about local native plants.

Numerous websites are also available, including those of the nurseries I’ve used, and a Google search for your area may find several more. One of my favorites has been that of High Country Gardens, in Santa Fé. They have a gorgeous, full-color catalog, and their specialty is Plants for the Western Garden, including prairie grasses and perennials in varieties that are often difficult to find or unavailable at local nurseries, and common and not-so-common wildflowers of almost any hue.

[Editor’s Note: Most local nurseries carry grass seeds and fertilizers specially formulated for drought- resistance and high-altitudes, and sell plants appropriate to your particular micro-climate. They’ll also help you with information on the care and feeding of plants, and on common pests, blights and problems in challenging mountain areas.]

A common misconception is that xeriscape really means zero-scape. My across-the-street neighbor has a zero-scape front yard, consisting entirely of gravel and some larger rocks, with a few Falugia Paradoxa to break up the expanse of limestone pieces. However, xeriscape gardening isn’t necessarily about how to arrange gravel in your spare time.

Instead, the operating principle of xeriscaping is efficient use of that scarce resource — water. This means grouping plants with similar water needs together, the use of mulch to minimize evaporative water loss, and in general, choosing plants whose water needs are close to what nature “normally” provides in this area. The shrubs across the street were fine, and in fact I have a couple of Falugia Paradoxa now myself, but I wanted more plants, less gravel, and I wanted many of the plants to be flowering or decorative, and if possible, native to Colorado.

PHASE 1

With limited income, I dipped my toe into xeric gardening last season by reworking and planting a “test strip” — a sad and neglected flower bed of sorts between my gravel driveway and the split rail fence separating my lot from the neighbors to the east. This strip is 93 feet long and 3 feet wide. I cheerfully donated the existing sad rose bushes to the neighbors, then dug up the entire bed. I purposely did not amend the soil, or add lots of fertilizer. Then came the fun part. I purchased a variety of plants from local nurseries and High Country Gardens. These included Falugia Paradoxa, Penstemons of several varieties, Cytisus Purgens, Liatris Punctata, Dianthus, Veronica Liwanensis, Aronia melanocarpa, several samples of Schizachyrium scoparium, in both Blaze and The Blues varieties, and several Hemerocallis varieties. All told, I spent about $300 on plants last spring.

I also made a trip to a local landscaping supply business and ordered two tons of pea gravel mulch, which was dumped in a pile on the driveway for $79, half of which was the delivery fee. A couple hours of shoveling and wheelbarrowing distributed the gravel 2O to 3O thick over the entire test strip. Through the summer, I hand-watered (via sprinkler can) regularly, because even xeric plants need water to get themselves established. I used 30 gallons of water every week or so on the roughly 300 square feet of the test strip. Few weeds came up through the gravel mulch, plants that were supposed to bloom did so, and I lost not a single plant through the growing season, though it remains to be seen how they’ll look after the winter.

Last fall, I planted several dozen spring-blooming bulbs, about 2/3 Crocus in several colors, and about 1/3 Daffodils and miniature Iris. I’m looking forward to the results.

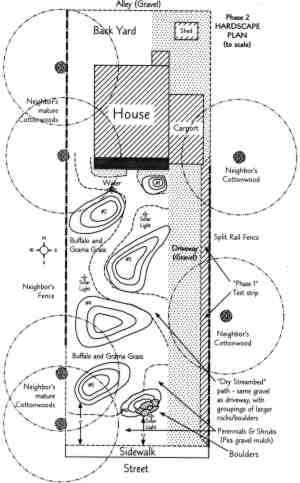

PHASE 2

This spring, it’s time to “hardscape” the main portion of the front yard. I want to install some low earthen berms to give the yard a bit of a vertical dimension, to steer rainwater (if it ever rains again) away from the house (which sits on a slab below street level) and toward the back of the lot, and to provide drainage for the additional plants I intend to put into the berms themselves. I also want a “dry streambed” type of gravel path, with occasional groups of larger rocks. Moving dirt isn’t terribly expensive, but adding big rocks is pricey. If the budget permits, I’ll put in more new plants this spring, after the hardscaping is done. I want to try some Buffalo Grass, which uses one-third as much water as Kentucky Bluegrass once established, and I’m fond of Blue Grama Grass, too. If the budget is too thin, I’ll mulch the berms with more pea gravel, water the existing grass in between the berms once a month as I did last summer, and wait until next year to plant the prairie grasses, shrubs, and wildflowers I have in mind for phase 3.

One neighbor was quietly skeptical when I announced my plan, but likes the result, another seems to approve, but frankly, I don’t care. So far, I’m very pleased with the result. I like the æsthetics, the idea of adapting my personal environment into the existing Colorado one, the lower water bills, and the potential of turning a scraggly lawn into something I’ll want to look at in every season of the year.

If you’ve read this far, you have figured out that Ray Schoch is a retired history teacher who lives in Loveland, where he serves on the planning commission. He also photographs wildflowers, and he visits Central Colorado from time to time.