By Jan MacKell Collins

Hike along Cache Creek outside of Granite today, and you are certain to run into folks all along the water. These aren’t your average outdoor enthusiasts; rather, the folks scrambling along the riverbanks are on a mission. They are looking for gold, which can still be found over 150 years after being discovered.

Cache Creek’s name is derived from the French word, “cacher,” meaning “to hide.” One story goes that around 1854, French trappers hid their pelts there, while another claims that explorers Kit Carson and Lucien Maxwell hid their supplies in the vicinity as they fled some Native Americans. Because of its odd pronunciation, Cache Creek was sometimes referred to as “Cash Creek.”Around 1860, placer gold was discovered along Cache Creek in what was then Lake County. They said that nuggets “big as eggs” were being found west of the creek around Lost Canyon. By late 1860, miners could be found panning for gold all through the area. Within seven years, some 49,000 troy ounces, or $200,000 of gold, would be found.

A series of small mining camps sprang up, but it was the community of Cache Creek which served as a supply town and the place to glean information about mining opportunities. In spite of being labeled “poor man’s diggings” by the Salida Mail, Cache Creek blossomed. Prospectors could make up to $20 per day. Notably, it was the first real town in today’s Chaffee County, with a population of about 300.

[InContentAdTwo] Even future silver millionaire H.A.W. Tabor tried his luck at Cache Creek. With him were his first wife, Augusta, as well as family friend Nathaniel Maxcy, miner Sam Kellogg and the Tabor’s son, also named Nathaniel Maxcy. The men made their own sluice boxes, but had trouble extracting the gold from the black sand deposits. Augusta was assigned the tedious job of using a magnet to separate the gold from the sand. Contrary to some accounts, Augusta did not run a boarding house or store at Cache Creek; within a month the party moved on to California Gulch some twenty miles away before making their fortune.

Meanwhile, Cache Creek’s supply stores served such smaller camps as Bertschey’s Gulch, Gibson, Gold Run, Ritchie’s Patch and others. Supplies were hauled to town by horseback and mule from a trail skirting the Arkansas River over two miles away. The homes of Cache Creek consisted mostly of log cabins. A cemetery was established in 1860 after the death of a young man from pneumonia. A year later, when the town of Granite sprang up two and a half miles away on the Arkansas, its residents also began using the cemetery. In spite of the convenience of Granite, however, many miners and their families preferred living near the diggings around Cache Creek.

On August 2, 1862, the post office was established as “Cash Creek.” Cache Creek was also incorporated, on January 10, 1866. Alas, the place was simply too far away from the Arkansas River trail. In October of 1866 the nearby town of Dayton established its own post office. A new mill was built near Cache Creek, but the Dayton post office was moved to the new county seat of Granite in November of 1868. Cache Creek’s population began to falter, and the post office closed on February 27, 1871.

[InContentAdTwo] By 1872, much of the area around Cache Creek was owned by the Cache Creek Mining Company. In Cache Creek proper, only ten cabins remained occupied. Most of the residents probably worked for the company, which employed sixteen men on both day and night shifts, who could mine upwards of a pound of gold per day, per man.

When Chaffee County was formed in 1879, the new boundary ran between Lake Creek and Cache Creek and directly through Cache Creek Park. In 1881 the Gaff Mining Company, in business since 1865, built a new two-mile- long bedrock flume. The outlook was good, there being gold “disseminated through all the ground which is free from bowlders [sic] or large rocks, and is easily washed.” Thus far, upwards of $800,000 in gold had been mined.

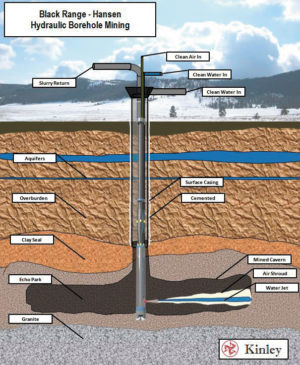

Next, in 1884, the Twin Lakes Hydraulic Gold Mining Syndicate, which had purchased the Cache Creek Mining Company, installed a tunnel between Cache Creek and Clear Creek. The tunnel cost over $40,000, but gold production nearly tripled. Over fifty men were now employed by the Syndicate, and gold production from May to November that year totaled almost $100,000.

By 1902, Cache Creek was quickly fading as new methods of mining downplayed the value of placer mining. Still, the Salida Record noted Cache Creek as “a neglected resource” of placer deposits. More people might have panned the creek but for a complaint, issued in 1903 by Cañon City some 100 miles away along the Arkansas River. Cañon City charged that the water was “polluted with quicksilver from the Cache Creek placers.” Articles about the issue appeared in local newspapers for years. The Cache Creek Placer closed in 1909, but the pollution problems continued well into 1911. This ugly turn of events was Cache Creek’s final undoing, and by 1929 nobody was mining the creek anymore. In more recent times, however, gold panning has once become a popular hobby in the area, and with good results.

Cache Creek’s empty buildings are long gone, but the historic cemetery remains. The graves consist of many residents from Cache Creek, but also Granite and other places. They include pioneer families, but as well as victims from some of the more violent crimes in Granite. Judge Elias Dyer, who was murdered in 1975, was initially buried there before being moved elsewhere. Other victims, such as David “Scotty” Hornell, whose neck was broken in 1887 during a fight with saloonkeeper and mine owner Enos Shaul, and railroad employee Pat Casey, whose throat was slit in 1888 by Niccolo Feminello, remain. Feminello, in fact, made history as the first man hanged in Chaffee County.

Other burials include that of miner Joseph Scheller who was killed in a mine cave in 1895, leaving behind a widow with five children. Deaths in 1898 included eighty-year-old Elizabeth Ball of Balltown and Nancy Bruner, wife of a Lake County constable. The graves of these early pioneers show the variety of people making up the area’s population. Some of those interred at Cache Creek have descendents who still visit their graves today.

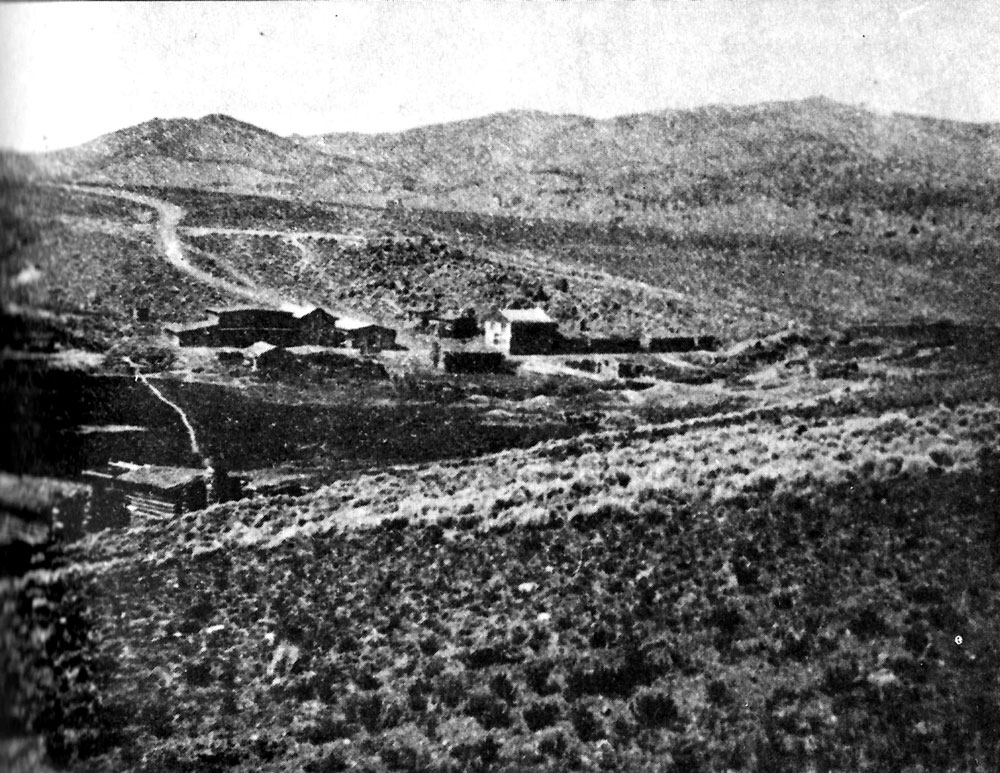

The townsite lies below the cemetery, where scant ruins identify buildings which appear in older images of Cache Creek. Walk behind the gate with the sign explaining about Cache Creek, and follow an old road down to access the town. From the townsite, you can also see the remains of a major flume up on the hill across the creek. This is all that remains of Cache Creek.

Jan MacKell Collins is a Colorado author who enjoys messing about in the woods, poking at old things.