by John Mattingly

Note: this is the first in a three-part series that looks at the current cultural sausage being made by our U.S. military, starting with the curious case of the American Sniper, followed by the troubling question of military honor and why our high-powered, big-dollar U.S. military keeps losing wars. The final piece will offer sensible and novel ways we can actually Make Peace on War.

Part One: No Thanks

The book and film American Sniper have, each in their own way, provoked an assortment of opinions about the life and times of Navy Seal and Iraq War vet Chris Kyle. Having read the book and seen the film, there are definitely different stories offered by each, but given the vagaries of national secrecy and Internet inaccuracy on one hand, and artistic liberties in writing and filmmaking on the other, a full and accurate account of Chris Kyle’s life would require a wildly devoted researcher.

One thing not in question is that Chris “The Legend” Kyle, was murdered by Eddy Ray Routh, a “straight up nuts” former Marine and also an Iraq War vet. Routh and Kyle, together with Chad Littlefield, a civilian and friend of Kyle, were apparently doing PTSD therapy at the gun range on Rough Creek Resort in Texas when Routh put a total of nine bullets into Kyle and Littlefield, including several in their backs, faces and heads. Routh then went to Taco Bell for a burrito.

Kyle claimed confirmed sniper kills in Iraq of nearly 200. Routh claims to have shot Kyle and Littlefield “because they would not talk to me.” Routh’s murder trial is commencing even as this article is written, Routh pleading innocent by reason of insanity. Kyle and Littlefield received a hero’s funeral; Routh might get life in prison without parole, though his insanity is probably no greater than that of the Iraq War in which he served.

This article will not drill into the competing story lines of Kyle’s life, nor will it offer an opinion as to whether the book or movie is more accurate or revealing. The circumstances of the Kyle and Littlefield murders – executions, really – on U.S. soil by Routh, a former U.S. Marine vet of the Iraq War, is a telling irony that brings up a relief map of questions.

How should, or can, non-military U.S. citizens act toward the troops of the Middle East wars? It is politically correct to thank the troops for their service, and this is offered in every conceivable venue these days, from football games to charity balls, from whorehouses to churches, from TV commercials to social media. All of this thanks is pouring out of our society when 99 percent of us – including over 500 members of Congress – have no real idea what that service was like, or even what it was for, exactly.

If for oil, the U.S. clearly didn’t secure it or need it. If to rid the world of a dictator, there were far worse than Saddam Hussein. If to protect our dearest freedoms, the result has been homeland security systems going somewhat berserk, limiting our freedoms in favor of security.

[InContentAdTwo]

The most often cited reason, “we went after them over there so they won’t get us over here,” fails to persuade because all the highly publicized terrorist attacks on the U.S. homeland have been substantially thwarted by civilians. It was brave civilians who brought down United Flight 93 during the 9-11 attack, while the Air Force was flying around Washington D.C. like high-powered headless chickens. The shoe bomber was tackled by a civilian, as was the Times Square bomber. The Columbine school shooting, Aurora theater shooting, Sandy Hook and literally hundreds of school shootings have been handled by civilians and law enforcement. Even in Boston, it was a civilian who found the kid while Boston mobilized something north of a billion dollars in response assets.

It’s time to turn the War on Terror over to the one group who has shown they can actually fight it. But civilian bravery and competence are not mentioned in Kyle’s book, or on display in Eastwood’s film. No, in most films and books about the Middle East wars, civilians are portrayed as either weeping or waiting, when they have actually been more effective in actual combat against terrorists than all four branches of the U.S. military combined.

And perhaps more telling: neither of Chris Kyle’s bios ask questions as to why and what we are actually doing in the Middle East. The movie and book present a consistent picture of a war that is simply there, going on and on in a strange, dusty territory, with U.S. troops running around, trying to figure out which people to shoot, and most desperate to save themselves.

The evidence is clear and somewhat embarrassing to the U.S. military: regardless of the form of attack, alert U.S. civilians have proved our best defense against terrorist attacks on U.S. soil. And that makes sense. To fight terrorism requires asymmetric tactics, not the usual blunt stick of massive military mobilizations. As this becomes clear, it has to weigh heavy on U.S. troops and vets stuck in an old symmetry that not only leads to defeat, but requires it.

Does anyone really believe that terrorists can be stopped with traditional military assets, or tanks, or bombs, or even snipers? Does anyone really believe that ISIL will attack the U.S. with bands of warriors brandishing AK-47s from the backs of old pickup trucks and march on Washington D.C. and cut off the head of our president? If ISIL should attempt such an attack, they will probably face a civilian arsenal in the U.S. that will wipe them out before the U.S. military can get its boots on, let alone on the ground.

Because the Middle East wars were fought by less than three quarters of one percent of the U.S. population – a smaller population demographic than American farmers – few of us have any direct contact with a person in the military. This in contrast to the years following WWII, in which almost every household in America had a relative connected in some way with the military. The contemporary distance from military personnel makes it even more difficult to relate to active and returning vets, so we simply thank them for their service but don’t really think about them, just as we “care” about national defense without demanding strict accountability for performance, or for the enormous, unchecked spending for “defense.”

So: Thank the troops for what? It’s a fair question, considering we lost the wars in which these troops fought, as recently declassified documents from military intelligence report:

“At this point, it is incontrovertibly evident that the U.S. military failed to achieve any of its strategic goals in Iraq. Evaluated according to the goals set forth by military leadership, the war ended in utter defeat for our troops.”

No genuine thanks or respect is due our military for such a defeat. In the last 13 years of continuous war, hundreds of majors and colonels and generals have been deployed to the Middle East theater. Available information indicates that, even though some of the upper brass were removed for sexual misconduct or speaking to Rolling Stone, none were relieved of duty for combat ineffectiveness, even though tactical defeats consistently outnumbered tactical victories. Some brass were promoted after tactical defeats on the basis of, of all things, minimizing their casualties. Code for: retreating.

By any standard of American values, nearly everybody in the military failed the job, from top to bottom. If the military were held to the same standards as U.S. corporations, or even a pro football team, the CEO or coach would be tossed out and replaced. But there is no such standard of accountability for our military. Instead, everybody in the military is a hero just for serving, and thanked for their service, even though the evidence is clear with the rise of ISIL, Boko Haram and jihadists everywhere: the service provided by our military created more terrorists than it killed. To now continue with bombing missions may only amplify terrorist resolve and magnify our defeat.

It’s little wonder returning vets are angry and confused. You don’t go to war for fun or for the experience. You go to war to win, to defeat an enemy by fatal force. It is the most onerous duty of a warrior, a duty in which loss of limb or eyeball or life are on the line in the cause of victory. For a real warrior it is better to have won the war and lost limb or life than to lose the war and save your life. The priority of the U.S. military in the Middle East was clearly the latter, which only humiliates its warriors. It’s really no surprise, then, that more returning vets have committed suicide than were killed in battle. And as the Routh murders indicate, it is no surprise that the U.S. military has created a new species of terrorist on U.S. soil: the nutty veteran with a gun.

“What is the best defense against a good guy with a gun?” – a question for Wayne LaPierre, President of the NRA

Next Month: The Horror of Honor

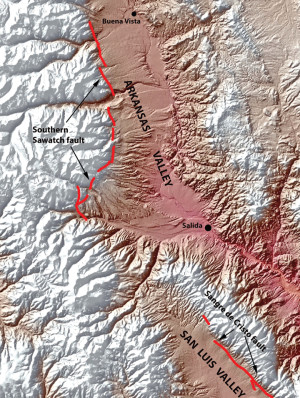

John Mattingly cultivates prose, among other things, and was most recently seen near Poncha Springs.