Article by Virginia McConnell Simmons

History – December 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

NEAR THE Continental Divide and Monarch Pass, Chaffee County has a mountain called Pahlone Peak. Considering all the attention that Ute Indians have received in this magazine lately, Pahlone Peak deserves a nod, but who was Pahlone?

Lord Byron wrote that glory depends “more upon the historian’s style than on the name a person leaves behind,” and this Pahlone fellow has been the victim of more than one historian’s style. But accounts by his contemporaries were also confusing.

Happily, geographers do things more simply. Once the United States Board of Geographic Names approves a designation, it usually sticks, so don’t expect the name of Pahlone Peak to suddenly be changed to Paron, Cotoan, or Friday Mountain in the near future. All these names are the alternative monikers of Pahlone, who was a son of Ute Chief Ouray.

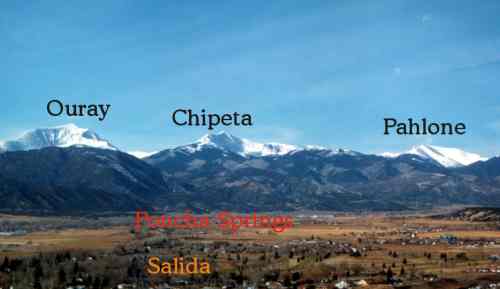

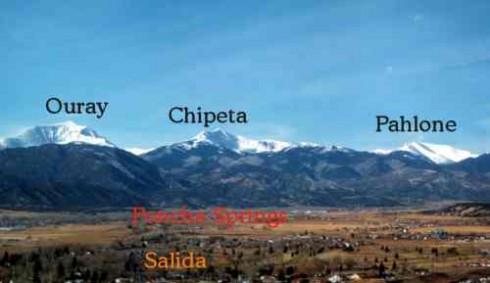

Pahlone Peak’s official location is Chaffee County, latitude 38º28’50″N and longitude 106º15’27″W on the USGS Pahlone Peak quad map, 7.5’x7.5′. The summit of this mountain is a short distance east-south-east of Monarch Pass and directly east of Mount Peck. The Colorado Trail passes Pahlone Peak on its west.

South of Pahlone lie two mountains named for better-known family members, Chipeta Mountain (12,853′) and Mount Ouray (13,971′) near Marshall Pass, with the elevation of Pahlone Peak (12,667′) being, appropriately enough, a little lower than them.

Recently the name “Paron” appeared instead of “Pahlone” in a new book, Searching for Chipeta, that caused a little confusion for its reviewer in this magazine. My guess is that the author, Vickie Leigh Krudwig, found Paron in David N. Smith’s biography of Ouray, and the variation is understandable. The problem stems from phonetic difficulties. Ute Indians had trouble articulating the difference between R and L, and thus Ouray’s own name was spelled Ulay in some early records (as with the Ute-Ulay Mine above Lake City).

Compounding such simple confusions, agents often threw up their hands when it came to the real tongue-twisters; thus we get a Northern Ute called David Copperfield. Therefore “Paron” will do, but I wonder about Smith’s definition of paron as “apple” because the Southern Ute Tribe’s dictionary shows masaana for “apple.” It is easy to become befuddled by personal names in any Indian tribe, including Ute. I haven’t even mentioned yet that Smith said Pahlone’s/Paron’s first Ute name was Queashegut, but his cousins called him Cotoan.

It seems fairly certain that Pahlone (I’ll stick with that name for now) was born about 1857 to Ouray’s consort, Black Mare. (Let’s remember that our dominant society’s concept of a spouse was not universal, and Native Americans had very different notions about family.) Pahlone might have been cared for by Ouray’s better-known consort, Chipeta, when Black Mare (1) died, (2) was displaced by Chipeta, or (3) hung around the tepee and participated in raising her own child.

WHILE STILL QUITE YOUNG, Pahlone became sufficiently accomplished as a horseman that by 1862 he was allowed to accompany his father on a hunt somewhere on Colorado’s plains. Clearly, he had the makings of a son of whom a father could be proud.

Here begins the tale that gave Pahlone a niche in history although, like just about everything else pertaining to him, this story has many variations. Somewhere along the South Platte River, maybe near Fort Lupton as some say, or much farther east near the Republican River as others say, Pahlone was taken captive by Sioux, according to some, or Northern Arapaho, according to others. Plains Indians were the Utes’ mortal enemies, and it was common for young captives to be taken and raised as their own. The grieving Ouray made great efforts to find him.

The remainder of this story will rely on information that was gathered by the late Ann Woodbury Hafen, one of Colorado’s reputable historians, some years ago. For an article “Efforts to Recover the Stolen Son of Chief Ouray” in The Colorado Magazine (vol. 16, 1939), she used documents gathered by the government after Pahlone’s whereabouts had become a federal case.

In 1872, the government was attempting to get the Ute Indians to cede lands in the San Juan Mountains, where the presence of precious metals was luring miners. The negotiations failed but were resumed the next year. The meeting place was at the Los Piños Agency No. 1, northwest of Saguache, where Ouray and Chipeta had a home on the agency grounds.

Both Los Piños’s Indian agent Charles Adams and Ouray’s associate Otto Mears had undoubtedly heard from Ouray about the loss of Pahlone, and Adams or Mears (most likely Mears, always the clever maneuverer) suggested to Commissioner Felix Brunot that the influential Chief Ouray might be swayed to lend his support at the second cession if the government would find Pahlone.

HAFEN QUOTED the following from Ure (Ouray) to Bruno, which she found in the record of the negotiations of 1872:

Some ten years ago the Utes had a fight with the Sioux on the Platte. We killed one Indian, and knew it was a Sioux by his shirt…. After the fight my boy, about five years old, was missing and a Mexican who traded with the Sioux has since told me that Friday had my boy, and a Mexican woman who was married to a Sioux also told me a year ago that she had seen my boy, and the Friday still had him.

Efforts began to locate Pahlone through different Indian agencies, and it was learned that, contrary to the information given by Ouray, the boy had been passed along from the Sioux to Northern Arapaho Indians and from them to Southern Arapahos. Friday was a Northern Arapaho chief, and Pahlone now was also called Friday. The closest anyone came to apprehending the young Friday was when an agent in Indian Territory ordered that some Arapaho warriors should be brought in to the agency, for the purpose of finding Friday.

OF THE 37 ROUNDED UP by older chiefs, 14 escaped, among them Friday. With the date nearing for the second counci1 when the San Juan cession was to be negotiated in 1873, Agent Charles Adams and Ouray met Commissioner Brunot in Cheyenne and applied some pressure regarding Pahlone/Friday, and he then was found in Indian Territory.

When questioned, he refused to acknowledge any relationship to Ouray or to the Ute Tribe, whom he spoke of as enemies. He wanted to stay with the Arapahos. He said that he was an Arapaho and his name was Friday and he insisted he did not know any Ute name, but Utes who met him said he was the Cotoan they had played with as children. When asked to tell about the fight during which Pahlone was captured, Ouray said it had taken place about 30 miles north of Denver, but the Arapahos disputed Ouray’s statements on this and every other point.

Although it would be impossible to determine the truth conclusively from the arguments, Washington was convinced that Friday probably was their man and brought him there to meet Ouray face to face. Seeing the pair together, everyone was convinced that they were, indeed, father and son, and the young man finally agreed to go to Colorado.

First, though, he wanted to say goodbye to his Arapaho friends, as Brunot told the story years later, and en route Pahlone died. With a mountain in Central Colorado named for him, however, it might be said that Pahlone did come home.

Virginia McConnell Simmons is the author of The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico, along with many other books of regional history. She lives in Del Norte.