Sidebar by Martha Quillen

Local Lore – December 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

THE LEGEND of the Angel of Shavano varies considerably, depending upon who’s doing the telling, but Harrington’s version is fairly faithful to a fable created by Corinne Harpending in the 1920s, and recirculated ever since.

According to Salida: the Early Years, by Eleanor Fry (edited by Dick Dixon), the shape of an angel was first noted on the face of Mt. Shavano in 1922, and afterwards, photographs and Harpending’s legend were widely circulated. Fry’s account says that religious people inspired by the tale actually made spring pilgrimages to view the mountain for a time.

But Perry Eberhart’s popular book, Guide to the Colorado Ghost Towns and Mining Camps, claims that there were two Angel of Shavano legends commonly circulated. The other, less popular, version told of an Indian chief’s esteem for the famous white scout, George Beckwith.

“Chief Che-Wa-No,” Eberhart wrote “had met Beckwith and had grown to respect him.” Thus after Beckwith was killed in an accident the chief prayed at the foot of the mountain, and afterwards “the Angel of Shavano returns to signal that the Indian’s prayer has been answered.”

Local oral variations often include a Ute paradise before the white man’s arrival; Indian princesses and lost lovers; and various tall tales about Chief Shavano. Yet such legends may well have developed decades after the mountain was named for the real Chief Shavano.

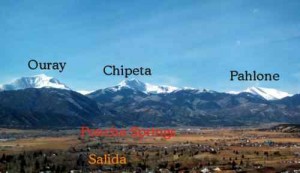

In Colorado Place Names, George Eichler notes that the name Shavano started appearing on maps after 1879, presumably in honor of the fact that Chief Shavano remained loyal to the U.S. during an uprising that year. A Ute war chief, medicine man, and leader, Shavano was a contemporary of Chief Ouray. His name has come down in myriad forms and spellings, and has been applied to numerous geographical features, at least one town, and countless commercial enterprises. In 1873, Shavano signed a convention between the Utes and the United States with an X, but his name was penned in as Chavanaux.

Eichler also wrote that a figure known as the Angel of Shavano “is the subject of numerous Indian legends.”

And as Walter Borneman and Lyndon Lampert tell it in their book, A Climbing Guide To Colorado’s Fourteeners,”there are numerous Indian legends,” but it is “virtually impossible to determine which of these legends is of the greatest antiquity, or which are even genuinely Indian in origin.”

IN THEIR BOOK, Borneman and Lampert include a legend about an Indian princess who knelt at the foot of the mountain praying for rain, whereupon her god demanded that she sacrifice herself for the sake of her tribe. And she did. But every year she returns as the Angel of Shavano, and when she weeps for her people her tears replenish the land below.

We sure don’t know whether this was a real Ute legend or not — since it does sound a mite too much like an Anglicized version of what an Indian legend should be. But the snow formation on Mount Shavano is certainly notable, so it no doubt did inspire Native American stories.

Many people, however, don’t think that the shape on the mountain looks much like an angel, or even human for that matter. In fact, Ed claims it looks an awful lot like Woody Woodpecker, and Columbine says it is definitely the Grinch. Another friend thinks it looks like a deformed white bird, which seems fitting, since it is as fragile and fleeting as peace.

The Angel of Shavano appears for just a few weeks to a month or so every spring. But she is presumably up there, all year long, waiting to serve the people of her valley.

Martha Quillen likes to get out and look at the Angel of Shavano when she’s not editing Colorado Central.