PARK AND CHAFFEE COUNTIES each have approximately 45 mining districts, geographical areas established during Colorado’s 1800s mining boom to specify individual mine locations. Many districts were named after a particular “strike,” a nearby town or even a memorable experience such as the early Snowblind District, the precursor to the Consolidated Montgomery District at the foot of Park County’s Mount Lincoln.

The Hall Valley Mining District was located in the farthest northwestern section of Park County that extends from the valley floor west of Kenosha Pass all the way up to the Continental Divide at 12,000 feet. It butts up against the Summit and Clear Creek County lines. A remote area, Hall Valley was nevertheless a good silver producer in its day, but not without its share of lawlessness and subsequent Wild West shenanigans.

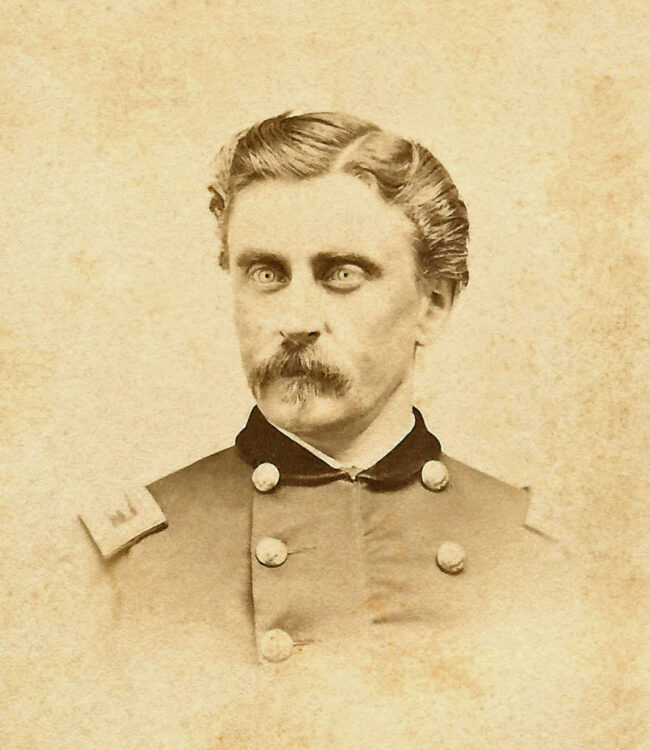

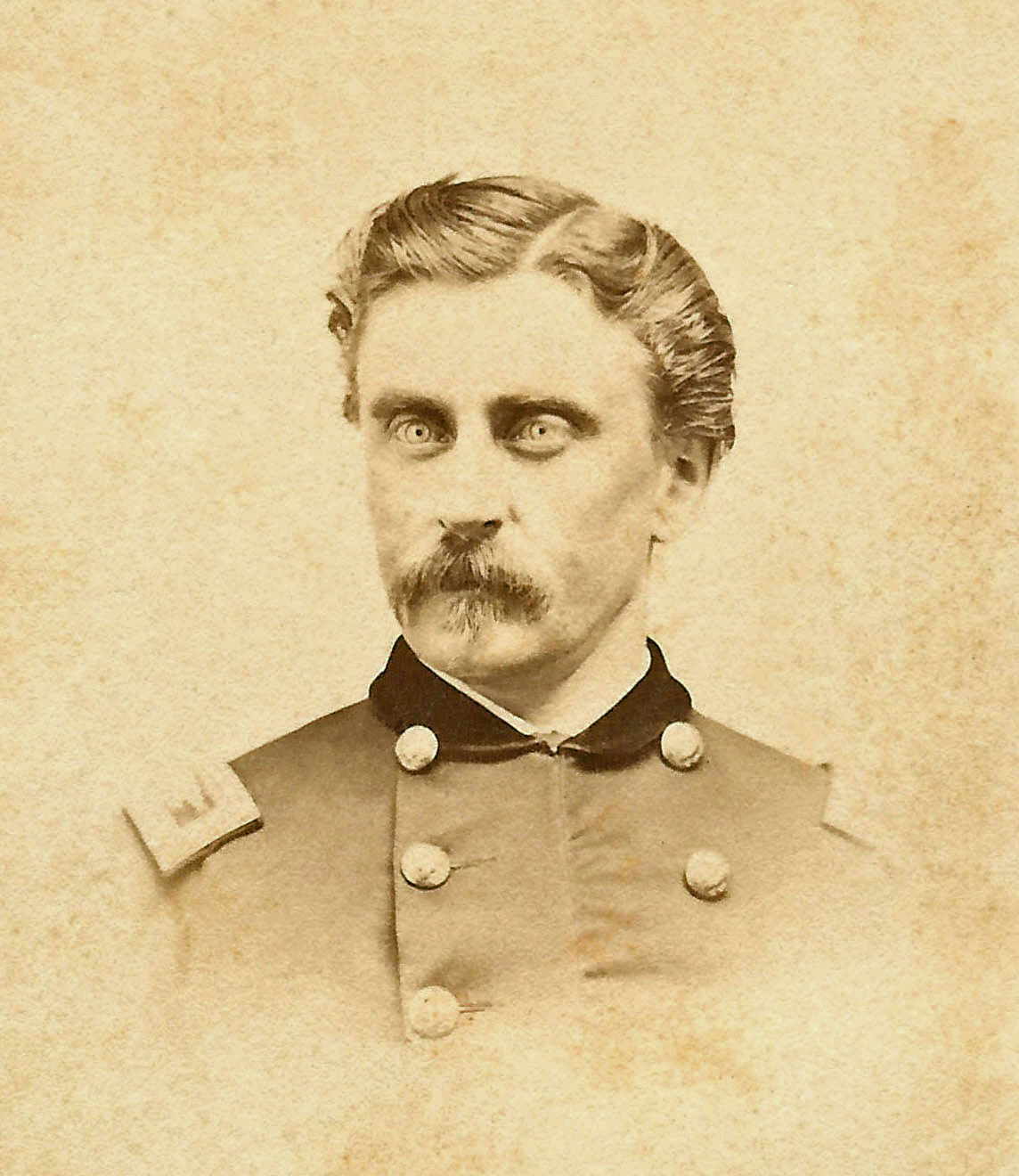

Col. Jairus W. Hall, July 1863. Taken shortly after the Battle of Gettysburg, where he was wounded.

Credit: George Wilkinson 4thmichigan.wordpress.com.

The district was named after Jairus William Hall, a decorated Brigadier General who fought in 90 Union battles including Gettysburg, where he was slightly wounded. After mustering out in 1866, Colonel Hall (as he preferred to be called) initially settled in Georgetown, Colorado, where he profited from his mining investments. He was even partners with General George A. Custer in the Stevens Mine.

In 1872, Hall and his family traveled over the range via Webster Pass to prospect, subsequently founding the Hall Valley Mining District, initially referred to as Hall’s Gulch or Hallsville. The Colonel was not the first person to mine up high at the top of the gulch; an Indian scout named Scott Shaw had prospected there years earlier and often visited the area.

Hall purchased the large Whale Mine in 1872 for $20,000, plus a few adjoining claims. He formed the Hall Valley Silver, Lead and Smelting Company with strong financial backing from a group of British investors. After building numerous mining structures including a reverberatory furnace, sawmill, assay office, boarding houses and a store, Hall Valley was up and running as miners poured into the valley to work.

Unfortunately, the camp soon acquired a rough reputation, prompting the Rocky Mountain News of August 16, 1873, to call it “the grand resort of a great majority of unhung rascals.” Because Hall Valley was 35 miles from the county seat of Fairplay and the sheriff’s office, the law was rarely seen.

To quell the lawlessness, Colonel Hall closed down a new saloon in August of 1873, owned by one Henry Hall (no relation). In response, H. Hall and his buddy “Big Mike” Boice began shooting up the town, even threatening to kill the Colonel himself.

The two ruffians were rounded up by an eight-man civilian posse and confined in a storage building for the night; however, some town vigilantes rousted the duo out of their sleep that night and promptly strung the pair up on one tree branch. The posse members then bought up all the whiskey and either poured it out or shot up all the bottles. Hall Valley holds the dubious distinction of the only double lynchings in the county.

The biggest fiasco came ten years later when mining foreman Jake Byard shot and killed Hall Valley newcomer Amos Brazille. The two had briefly met and played a game of cards and joked around in George Campbell’s saloon, but when the joking turned to arguing, Big Jake, who stood six feet, five inches tall, stormed outside, returning through the saloon’s back door. Cracking it halfway open, he stopped at the top of the steps and yelled, “God damn you, take that!” Firing directly at Brazille from five feet away, the bullet mortally wounded the poor fellow, who fell to the floor, begging the onlookers to “Please write to my father and tell him that the long son-of-a-bitch has killed me.”

Byard was captured by two citizens who found him hiding nearby and hauled him off to jail. He soon spied a metal file tucked in the corner of his cell and used it to whittle away at the iron bars. Lucky for him, the jailer allowed another inmate named Frank Record to play his violin after dinner so while Record was fiddling, Byard was filing—in unison!

Big Jake broke out of jail in March of 1884. The last word was that he had absconded to his father’s cabin near Buffalo, Wyoming.

Hall Valley continued to produce some excellent silver, even after Colonel Hall and his family moved on; he eventually moved to London, England, where he is buried in an unmarked grave.

Today Hall Valley is accessible via a five-mile drive on County Road 60 starting on the east side of Kenosha Pass and ending at the Hall Valley campground. The campground is where many of the miner’s boarding houses had been located, when it was a bustling 1879s community.

Central Colorado has some of the most intriguing Wild West tales!?

Christie Wright, a semi-native, is more than familiar with the “bad guys,” having worked as a Colorado Probation Officer for 20+ years. Her book, “South Park Perils: Short Ropes & True Tales” details Park County’s fascinating Wild West era.

Always enjoy Christie Wright’s books.

Thank you for this story of Hall Valley and Colonel Hall.

-Paul M.