By Ann Marie Swan

Salida painter Michael Haynes’ vision of American history is seen by millions, and he’s determined to get it right. Every eagle feather, every pewter button, every coat worn in battle by a particular regiment on a particular day is grounded in fact. Haynes builds objects and illustrated actions into scenes, moments in time and culture, where every character has a backstory. But it may not look like the history you learned in school.

“

My work is all about blowing up historical myths,” Haynes said.

He gives the example of Meriwether Lewis wearing a tricorn hat and William Clark wearing a coonskin cap in stereotypical images from their Corps of Discovery Expedition from 1803 to 1806 through the uncharted American interior to the Pacific Northwest. Neither style would have suited a military-like expedition and wouldn’t likely have been permitted. And these hats just weren’t fashionable at the time. Scholarly research doesn’t support it, according to the book Haynes co-wrote and illustrated, Lewis & Clark Tailor Made, Trail Worn: Army Life, Clothing & Weapons of the Corps of Discovery, with author Robert J. Moore, Jr. (Farcountry Press, 2003).

This realization was unsettling for some, but eventually people “fully embraced” it because they were “getting closer to the truth,” Haynes said. His work with Moore rounds out a complete record with the cultures that influenced the expedition and the weapons, accessories and gear that contributed to its success. “My work has to have educational value.”

It’s purposeful, too. Haynes doesn’t just paint a scene: He directs it. He positions characters consciously with luminous micro-detailing. Light and shading values deliver viewers of his artwork right to the heart of the matter. He gives weight to specific characters and creates a pathway into their inner lives. One painting is an early morning scene with Cherokees on the Trail of Tears, part of a Natchez Trace series commissioned by the National Park Service in 2015. An infant in a brilliant red trade blanket is dead in the mud and the mother is unhinged with grief. Mother and child are relatively small figures with large psychological charges inside a crowd in the grips of being forced to move west.

But the conviction within the painting isn’t finished. A Cherokee man pulls the attention straight into his eyes. The only choice is to meet his gaze. A silence hangs afterward.

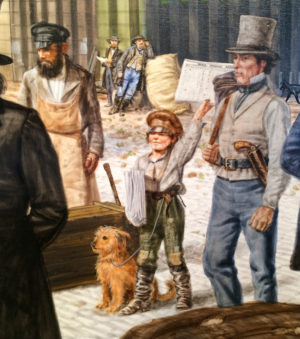

Haynes’ latest project is a series of mural-like paintings, commissioned by the NPS, for the opening of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, the renovated museum under the arch in St. Louis. Haynes has a 4-by-7 painting on his studio wall of this same, imagined place in 1850, when St. Louis was bustling with French colonists, Osage and other Native Americans, and Irish and German immigrants. He creates a canyon-like effect with belching steamships on the left and walls of waterfront warehouses on the right. It’s a collection of instances and encounters, a traffic jam of emotions with everyone who would have been in the frame at the time. Characters step in, then out.

Haynes’ latest project is a series of mural-like paintings, commissioned by the NPS, for the opening of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, the renovated museum under the arch in St. Louis. Haynes has a 4-by-7 painting on his studio wall of this same, imagined place in 1850, when St. Louis was bustling with French colonists, Osage and other Native Americans, and Irish and German immigrants. He creates a canyon-like effect with belching steamships on the left and walls of waterfront warehouses on the right. It’s a collection of instances and encounters, a traffic jam of emotions with everyone who would have been in the frame at the time. Characters step in, then out.

The focus is directed toward the missionary Father De Smett talking with a Nez Perce. Hints of poverty and new beginnings are evident with a wide-eyed immigrant family walking down and off a plank into the cosmopolitan busyness. Bewilderment stamps their faces. The movement within the painting keeps the viewer going from mini-scene to mini-scene. And it’s impossible to leave the painting without seeing the black slave, slightly shadowed, slightly sidelined, on whose back this country’s wealth was built.

Haynes will be in St. Louis, his hometown, for the museum’s festivities in July. He’ll circle back to his roots, where he gained some notoriety creating art for the St. Louis Post Dispatch, back when daily newspapers were strong. After computers changed the employment landscape in the mid-1990s, Haynes adapted with more civil war and Lewis and Clark art in galleries. Besides the NPS, the U.S. Forest Service, the Department of Defense and other heavy hitters commissioned artwork. The White House even acquired one of Haynes’ Lewis and Clark pieces.

Haynes enjoyed this good fortune to fully live and work as a painter. All for his love of history.

Haynes’ ancestors, William Bradford and William Brewster, came over on the Mayflower. His great-great grandfather, Lt. Col. Rufus Dawes, fought at Gettysburg in 1863. Haynes walked these same grounds. This connection with his own family history moved through him and stayed. Now, he’s creating paintings for the Gettysburg National Park.

[InContentAdTwo] Haynes is involved in the living history of the civil war, too. He’s participated in enactments, and met experts to contact on what boot was worn or which pipe was smoked. He’s been in movies, including the Oklahoma land rush scene in “Far and Away,” 1992, and the Battle of Olustee scene in “Glory,” 1989. These experiences fed his desire for more research and interior truths, and deepened him as an artist. In this way, he infused himself into his artwork, and, in the process, made it authentic.

Haynes has teamed with private collectors, too, and painted weapons used by tribes native to Missouri. He gave these static weapons new life in paintings of a warrior swinging a hatchet, then another holding his weapon high, attack-ready, while riding a horse. Young boys, especially, liked the artwork. And, in these images, Haynes made history cool.

“I love getting kids fired up about history,” he said.

The stories should come first, the dates later, he said. A kid can connect with a 13-year-old girl, rocking back and forth in a covered wagon for months and eating bad food and seeing wild, unimaginable things.

Haynes has painted images of Sacagawea, a member of Lewis and Clark’s expedition, reproduced in textbooks. Unlike Anglicized versions of Sacagawea, her face is round and true to that of a young Shoshone woman with a baby boy. And she’s not pointing west and showing Lewis and Clark the way. She’s more natural, more real than that. She’s the woman who certainly taught Lewis and Clark some things. But more than anything, Sacagawea protected them indirectly because native people watched the expedition for weeks but declined to attack with her in the camp. She lightened the homesick explorers’ evenings with her baby bouncing on their laps around campfires. Native Americans who tracked the expedition were more curious than aggressive with Sacagawea there.

Haynes shoulders responsibility as a guide on inroads to history. “Man, this is what they think of Sacagawea,” Haynes said. “I better get this stuff right.”

When Haynes creates his historically accurate art, he time-travels in a sense. And if he could go back in time, where would it be? Who would he be? Haynes struggles at first to answer. So many choices. But he settles on being part of Lewis and Clark’s team in August 1805. He imagines himself cresting the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass, today’s Montana-Idaho border. Standing next to Lewis, Haynes would look west and see mountain range after mountain range topped with snow, and no sign of the Pacific Ocean.

Haynes said, “To stand that ground and feel that disappointment, then, later, the determination to move forward would truly be something. That moment would have been as good as any.”

Ann Marie Swan is a freelance writer, editor and librarian in the Salida area. Swan is happy to see that in paintings, Sacagawea is not wearing a short, tight animal-skin dress that is historically inaccurate.