by George Sibley

We’re in the middle of an election season again, and again I find myself asking: Are we humans really ready for democracy? Have we evolved that far?

That question rolls around in my mind as I watch the current political campaigns, where we are being asked to decide on our next governor and senator based on a constant barrage of outright lies, twisted facts and policy statements obviously tailored by media experts to sort of reflect what we’ve been conditioned to believe we should want to hear, with no historic evidence to indicate that the candidates saying them so guilelessly and guiltlessly actually believe them, or would ever be likely or able to carry out their promises if elected. That most of these come from the right begs the question: would whoever is throwing this expensive barrage of dreck at us be doing it if there was no evidence that people actually believe these things uncritically – and vote accordingly? Which takes me back to the original question.

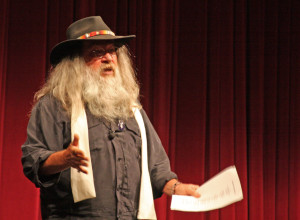

I got in a short discussion about this with a couple of intelligent and informed people after a recent reading at the local library. One of them reminded me that corrupt and money-muddied campaigns are nothing new; Mark Twain, he noted, commented a century ago on “the best Congress that money could buy.”

Yes – but that was a hundred years ago; shouldn’t we be seeing some improvement through time? And could anyone seriously deny that the purchase of this malicious kind of political power is a more proficient art now, with all the new media, than it was in Twain’s time?

I do think we have something pretty close to democratic governance at the local level – town, city, county governance. We select our local leaders in a pretty direct way, and they generally lead the way the horse leads the carriage – they are working on our behalf, and do try to figure out, formally and informally, what we would like them to do on this or that issue. A few of them sometimes get “captured” by local factions – developers, anti-immigrants, Main Street, to the exclusion of the whole community – and they sometimes take the bit in their teeth and run their own course, but they do so knowing they will pay for it at the next election, unless they can actually convince us that it was a beneficial move.

Political parties make little difference at the local level, where problems and situations do not fall so neatly into liberal-conservative categories (not that I would accuse either major party of any purity on those categories); and too many of us know the candidates more familiarly than the pre-programmed smiling automata on TV parroting what their staffs say will sell to the hicks. In Gunnison County this election, the Democrats did not bother putting a county commissioner candidate up against the Republican incumbent; they know there is not enough dissatisfaction with the incumbent – even among Democrats – to unseat him. The local Tea Partiers are probably more frustrated with him than the valley’s liberals.

It’s at the state and national levels that our pretensions toward democratic governance, “by, for and of the people,” have been falling apart. This is not a new thing, but it goes all the way back to the colonial roots of the republic and the conflict between those who wanted to keep political power as local and close to the ground as possible, and those who wanted – well, a central bank. Okay – too simple. But so is the picture of our founding fathers receiving the Constitution with unanimous accord from God; we need to remember that the Constitution was born in and of a conflicted society where roughly a third of the people had hoped the British would beat down the country rebels so the Industrial Revolution – to which the “American Revolution” was really just an episode of agrarian counter-revolution – could proceed apace. Which it did: from the early 1880s on, the urbanization and industrialization of America proceeded unchecked until the irregular beginnings of a “non-metropolitan turnaround” in the 1960s. (That’s us – any place in “rural” Central Colorado where the population has been gaining or holding even over the past half-century.)

This question rises: is government by, for and of the people truly possible when the people number 20, 50, 100, 300 million? Spread (in concentrated urban globs) over a land of diverse geographies but increasingly bound together by a common urban-based internet culture? This was a question being asked even before the internet was envisioned. (James Madison tried to answer it in “Federalist Paper 10.”)

Walter Lippmann was an American philosopher-writer who grappled with this question: In interconnected urban environments, with huge and complex social, financial and economic structures and infrastructures, all needing construction, operation, maintenance, regulation, etc. – how could an individual citizen possibly know enough to really participate actively in his or her governance?

Lippman believed that such a society of necessity had to be run by specialized “elites” – managers and governors, financiers and accountants, engineers, scientists, lawyers and legislators, journalists. How else would a modern city get plumbed, wired, operated and maintained? And how could the ordinary citizenry understand such systems well enough to analyze and evaluate them – and their operators? The people would know when the systems were not functioning, but would have no idea how to fix them.

As Lippmann saw it, there was only one way to run a mass society with at least a modicum of democratic process: that was for each of those elites to tell the people enough about the needs and problems of each system so that the people would consent to paying for, or otherwise going along with, what the elite group wanted (more or less regulation, bonding for expansion, whatever). They needed, in short, to “manufacture consent” for what they believed the people needed. This required something that did not exist then, and arguably still does not exist: objective media to communicate what the elites wanted to the people in as balanced a manner as possible, so that the people would be able to make good decisions, in voting for their representatives, or passing this or that bond issue, or making other public decisions.

There’s neither space nor need to go deeply into Lippmann’s musings on this dilemma of large-scale complexity confronting democracy. But that should be enough to reveal some basic flaws he either didn’t anticipate or glossed over. The first would be the extent to which the system depended on the honesty and openness of the elites, and their willingness to actually work on behalf of the masses, to lead the way the horse leads the wagon. And while there are many good public servants, there are also some very corrupted elites whose main objective seems to be to lock up as much of the nation’s wealth (or at least its money) as they can, and to use their resulting ability to purchase power to minimize their public responsibilities and maximize their private gains.

Another problem is the media themselves. Lippmann imagined the modern journalist as a kind of highly educated scientist of facts and figures, able to objectively present the complexities of modern life in ways understandable to a reasonably intelligent citizen. We do have journalists who approach that standard (me and thee, brother), but for the most part our media – especially radio and television – are a mess, their journalists intellectually underequipped, mired in conventional thought, and “objective” only in that they lend their media to the uncritical display of whatever anyone wants to tell them.

The third problem is we the people. We let them all get away with it. We express cynicism about the government – then naively vote the same government back into office. We hope that the legislators will pass laws making the way they got elected illegal, or that the judges they install will stop ruling that money is speech: one dollar, one vote. But ultimately only we can change the situation, by ceasing to vote for purchased egomaniacs and sociopaths, and starting to demand that candidates positively address the problems we face rather than negatively focusing on the failings of their opponents. (Where is climate change in this election?)

If we cannot do that, then we warrant the century-old judgment of the true journalist Lincoln Steffens: “The misgovernment of the American people is misgovernment by the American people.” If we don’t make it work, it never will. But who has the time for that – the time to even go to the fact-checking websites? Or the energy for it, on top of what’s required just to stay functional in one’s own life?

We could do better, but only if we do it. So back to the original question: Are we humans ready for democracy? Have we evolved enough to realize, down on the ground, the magnificent systems we can envision?