By Mike Rosso

It wasn’t quite a napkin, but a few quick strokes on the backside of an appointment card led to the design of one of the most recognizable airport terminals in the world.

Retired architect Jim Bradburn, who currently lives outside Westcliffe, Colorado, recounts how those scribbles were eventually transformed into the tent-like structure known to most Coloradans as the Jeppesen Terminal at Denver International Airport (DIA).

Bradburn, a graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, first came to Colorado in 1976 to oversee the construction of the Helen Bonfils Theater Complex for the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. At the time, he was working for the architectural firm of Roche Dinkeloo and Associates of Hamden, Connecticut.

Upon its completion in 1980, he decided to stay in Colorado and teamed up with Curtis Fentress, whom he was introduced to by a mutual friend. Fentress was known for his design of the Rocky Mountain Headquarters of Amoco in downtown Denver. They started Fentress Bradburn Architects (“with four gorgeous women and an older guy,” as Bradburn described it) and eventually became the largest architectural firm in Denver, employing over 100 at its peak.

Upon its completion in 1980, he decided to stay in Colorado and teamed up with Curtis Fentress, whom he was introduced to by a mutual friend. Fentress was known for his design of the Rocky Mountain Headquarters of Amoco in downtown Denver. They started Fentress Bradburn Architects (“with four gorgeous women and an older guy,” as Bradburn described it) and eventually became the largest architectural firm in Denver, employing over 100 at its peak.

As his own background emphasized engineering, Bradburn did most of the production work at the firm but had some influence on the designs. One of his first projects with the new firm was the restoration of the Navarre Building, located across from the Brown Palace in downtown Denver, which is now home to the American Museum of Western Art – The Anschutz Collection. While at Roche Dinkeloo, Bradburn had worked on several projects at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Museum work became one specialty for the new firm.

In the early 1980s, the Federal Aviation Administration was concerned about the proximity of the old Stapleton Airport to downtown Denver. There was also concern about the airport’s factor in limiting building heights in the downtown area due to downtown being in the path of incoming and departing flights.

Then-Denver mayor Federico Peña was tasked with determining a new location and with hiring a firm to design the new airport. He also put together a blue-ribbon panel of Denver’s movers and shakers to help steer the design of the facility.

The city had initially hired architect August Perez of New Orleans, a friend of Mayor Peña’s, who envisioned a terminal based on a palatial 19th century-style train station, complete with huge riveted beams and massive skylights.

The Fentress Bradburn firm was hired to be the production architect for the project. It was to develop the Perez scheme – to establish the design and budget, to produce a set of instructions (blueprints, working drawings and construction documents), to put the project out for bidding, and then to oversee the construction phase. Bradburn’s firm was also responsible for determining if the Perez design was on budget and within the established timeline. Perez’s proposal came in of $54 million over budget and could not possibly be built in the time frame established. It was rejected by the blue-ribbon panel.

“We got this pile of drawings that were basically useless. On top of that, they hadn’t worked out anything engineering-wise,” said Bradburn.

[InContentAdTwo]The city bought out Perez for $6 million but literally had to go back to the drawing board.

Bradburn recalls a meeting with the manager of the Denver Public Works Department, Bill Smith, who was overseeing the new airport construction, and airport director George Doughty.

“I said to them, what do you want us to do? And they said, can you help us here? I replied, give me two weeks.”

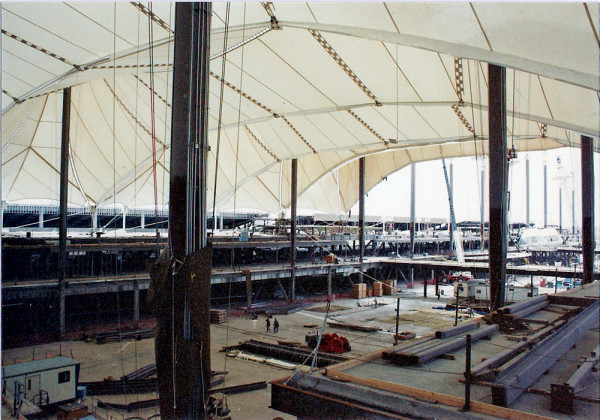

In the scheme of the entire airport, the terminal was given a certain amount of real estate, and designers had determined the location of the terminal, with east and west access for passenger pickup and drop-off. The basic layout was retained, but it called for a central open area requiring a 150-foot span.

“This needs to be cabled,” thought Bradburn. “To get across this span the fastest and cheapest way, solving two problems – budget and time – is through cables. Curt and I went out for lunch, and we used to have these little cards our secretaries gave us with all of our appointments and whatever, and on the back of that I drew this simple tent-like structure and said, it needs to be like this.”

“I pictured an encampment of Native Americans on a bluff,” he said, while speaking of his vision of white teepees rising out of the grasslands. “I wanted our architecture to acknowledge the original inhabitants’ architecture and be sympathetic to the regional environment.”

Bradburn then called an engineering friend in New York, asking for the number one fabric tensile membrane structural engineer in the world. The reply was Horst Berger, originally from Germany but now in New York, who had designed the Hajj Terminal at the King Abdulaziz International Airport in Saudi Arabia. That terminal is known for its tent-like roof structure consisting of 21 “tents” of white Teflon-coated fiberglass fabric suspended from pylons, which help accommodate the huge number of pilgrims who take part in the annual Hajj – up to 80,000 travelers at the same time.

Meanwhile, Bradburn was investigating other structures that incorporated tensile membrane structures, such as a convention center in Vancouver, B.C. and a mall in Toronto. He brought Berger out to Colorado and introduced him to the chief designer at the firm, Mike Winters.

“In two weeks we came up with a tensile membrane structure for the terminal, pretty much what you see today,” said Bradburn.

The firm then invited Smith and Doughty to their conference room. Knowing that Smith was an engineer, Bradburn had attached all the engineering, maintenance, budget and speed of construction aspects of the idea to the wall and displayed a prototype model made of Lycra, explaining to the two men why this made sense. The detailed explanation of the tensile membrane structure demonstrated that it clearly solved the problems of budget and completing the construction on time.

“A tent?” was their first reaction, Bradburn recalled. “I went through all the reasons and by the time I was done, Bill Smith was down on his knee, looking inside the model with a smile on his face, and I thought, gotcha!”

They took this design to the blue-ribbon panel and immediately received a stamp of approval. Mayor Peña, though, was concerned that the concept of comparing it to native teepees might be offensive to some, so it was settled – the official line was that the structure was to represent the mountain peaks of the Rockies.

The fabric used on Jeppesen Terminal (named after famous barnstormer and mapmaker Elrey Jeppesen) is a woven fiberglass, which is coated with Teflon and is produced by Birdair, Inc., a division of Corning in upstate New York. There are two layers of fabric at DIA: the lower layer, which is seen upon entering the terminal; and the outer layer, which is structural and is seen as you approach the terminal. It is cleaned periodically using soap and water and an over 50-year life span, according to Bradburn.

Bradburn was influenced by his early employer and mentor, John Dinkeloo, who had worked with famed Finnish architect, Eero Saarinen who among other projects, had come up with the design for the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.

“DIA was the high point of my career, in the sense that it allowed me to apply a lot of those things I learned from John into this building.”

DIA finally opened in 1993 after some infamous glitches with its automated baggage system (not part of the firm’s responsibility). It is the largest airport in the United States by total area. In 2013, it was the fifth busiest airport in the world by passenger traffic, and it has the longest public use runway in the United States.

Fentress Bradburn Architects went on to design the Incheon International Airport in South Korea, the Santa Fe Community Convention Center and the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, a 51,000 square foot building with its lichen-covered natural stone façade inspired by the adjacent outcroppings of rock.

Bradburn retired from the firm in 2004 and moved to Westcliffe with his wife Gayle that same year. He designed all of the buildings on their property, including a solar heated greenhouse and an observatory, where Jim likes to indulge in one of his many passions: astronomy. The observatory includes a 17” computer operated telescope with a camera for pictures of deep sky objects. Bradburn enjoys sharing the viewing with friends, but especially with kids from the local school.

He chose to retire in the Westcliffe area for its proximity to some of his favorite climbing mountains, including the Crestone Needle, which he’s climbed three times. Bradburn has also summited all of Colorado’s Fourteeners, as well as Mount McKinley, Mount Aconcagua in Argentina, and Mounts Cotopaxi and Chimborazo in Ecuador. Since moving to the area from Deer Creek Canyon near Littleton, he and Gayle have put their 446 acres of property in a land trust through the San Isabel Land Protection Trust. The lack of city lights in the valley also makes it a perfect place for stargazing, far from any airports.

Thanks for this fascinating feature about Jim Bradburn’s design of the DIA terminal. I’ve been curious about it since moving to Colorado–the background of this stunning design and also how it’s kept so clean! Great photos, too.

This Bradburn fellow sounds like an interesting guy. Thank you running this story!

More than an interesting guy. I have been in touch with him via E-Mail Re: astronomy and Dark Skies.

JB

What I find most fascinating is that mayor Pena’s architect friend got paid 6 million dollars for a design that was worthless. Sorry Denver tax payers! I also love the political correctness that requires the city to change the architect’s vision from tepees to mountains to avoid offending anyone. Priceless!!

To Jim Bradburn;

I’m 61 and I’ve been interested in astronomy my entire life!

As far as I’m concerned, you are the finest architect in the world!!

I’ve been to Denver once, a long time ago, and I would love to go back

and see the tents.