By George Sibley

Part I: The “Political Infrastructure” for Trans-mountain Diversion

Driving down U.S. 24 from Leadville to Buena Vista, along the Arkansas River that carved the valley, you don’t have the feeling of traveling past a man-made waterworks. It is in fact a beautiful stretch of river that looks quite “natural.”

You have to know what you are looking for to see the waterworks – for example, between Granite and Buena Vista, looking up on the hillsides across the river, you’ll see a barnlike industrial structure – a pumping plant, pulling water from the river and pushing it through the mountains to another natural-looking waterworks across Trout Creek Pass, in the South Platte River tributaries.

But for most of the rest of it you have to leave the highway for less-traveled roads. For example, a side trip up Colorado 82 to Twin Lakes, which is now more human-enlarged reservoir than lake, and farther uphill and off the road, a tunnel mouth – and somewhere around the reservoir, the end of a long conduit. A trip on unimproved roads to Turquoise Lake – also more reservoir than lake – would lead you to the upper end of that conduit taking water from the lake, and three tunnel mouths up in the surrounding hills bringing water into it.

These – and the natural-looking river that connects all the parts – are all central elements of two large water projects bringing water from the Colorado River headwaters through the Continental Divide to the cities and farms of the Arkansas and South Platte River valleys. They, in turn, are just two parts of a much larger system of waterworks all along the Continental Divide in Colorado that carry around 170 billion gallons of water a year from the Colorado River Basin to the South Platte and Arkansas Basins – a system of waterworks that might be called, in total, the connections creating the state of Colorado as we know it today.

The largest set of elements in the upper Arkansas waterworks is the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, which was created – on paper – by the U.S. Congress fifty years ago in 1962, after a long political struggle that went back to the 1930s, when southeastern Colorado was part of the Dust Bowl. But to many people in the Arkansas River basin, especially downstream in that farmland, the Fry-Ark Project is only a modest piece of what was a much larger dream of water moved through the Divide to grow food for cities to consume. That larger story is what we’re going to look at in three parts, from the vantage point of Colorado Central, looking both ways across the Divide.

The story begins with several historical emergences and convergences. We could begin with the emergence of the State of Colorado itself – a purely political abstraction, four lines of longitude and latitude laid down on the map with no connection to any natural geography at all, its only design an effort to encompass all the perceived metallic wealth in a territory not yet staked out by other claimants. As such, it is like a political blanket laid over a natural fence, which is the Continental Divide. The way the natural climate works, the west side of that “blanket” gets about 80 percent of the moisture that falls on the blanket, while the east side is semi-arid, a region where agriculture is only possible with irrigation.

But when people came to this abstraction called Colorado, the majority of them – 90 percent – settled on the east side of the blanket, partly because the West Side was still an Indian reservation until settlement was well underway, but partly also because it was easier to live on the high dry plains east of the Divide than in the narrow and isolated mountain valleys of the wet west side.

That imbalance of water on one side of the Divide and people on the other side converged with three other things. One was the evolution of a somewhat libertarian law for distributing water – essentially a Lockean “first come, first served” doctrine allowing individuals to appropriate water from the “commons” for personal use only (no tying up water for speculation purposes). Once water was so appropriated by a user, its use became a property right, so long as the user kept using the water. The owner of the right to use the water could sell that right to another, who did not have to use it the same way or in the same place, but could file for a new use in a new place – even in another watershed – while retaining the same seniority for use in the event of low water years.

It is worth noting that Colorado’s evolving water law was enshrined in the Constitution as an appropriation right that would “never be denied.” Its senior priority conditions were designed to administer temporary shortages, but it was essentially based on a water supply presumed to be as inexhaustible as the growth of the population and its economy.

That right to move water around the landscape – even across the Divide – would have meant less, had it not been for the convergence of that body of law with the emergence of heavy technology early in the 20th century. This convergence/emergence enabled the construction of dams, canals and other waterworks once only dreamed of. Projects like the Panama Canal or Hoover Dam were inconceivable without the power first of steam, then the internal combustion engine.

Another convergence was the collapse of the capitalist market system around 1930, and the emergence of the Keynesian political economy in the early 1930s via the New Deal, making large quantities of federal money available to stimulate the national economy through public projects that included moving large quantities of water from the wet side of the Colorado blanket to the dry side.

In 1935 Governor Ed Johnson created the Colorado State Planning Commission to organize the state’s appeals for federal assistance from the Public Works Administration, and its first (and only) director, Edward Foster, articulated the idea of three huge water projects:

1. Bringing water from the upper Colorado River tributaries to the farmers of the rich but semi-arid South Platte basin.

2. Bringing water from the Blue River to the incipient metropolis growing around Denver.

3. Bringing water from the Gunnison River to the farms of the Arkansas River valley.

Water users on both slopes put together organizations in the mid-1930s to stake out positions relative to the big picture articulated by Edward Foster: South Platte farmers created the “Northern Colorado Water Users Association”; Arkansas Basin farmers created the “Caddoa Reservoir (an early name for the reservoir ultimately named for Arkansas Basin Congressman John Martin) and “Arkansas Valley River Basin Conservancy and Improvement District.”

Denver already had its Board of Water Commissioners – which was already at work on the Moffat Tunnel Project, lining the Moffat pilot bore with concrete for carrying water collected from the Fraser River tributary streams.

On the West Slope, which had nothing to gain and everything to lose from Foster’s big picture, water users in the Colorado and Gunnison River basins created the “Western Colorado Protective Association.” They knew the water law was against them, but they wanted to do what they could to keep enough water on their side of the Divide for some degree of future development. The rest of the state tended to forget that several million acre-feet of Colorado River water had to leave the state for the downriver states, in accord with the Colorado River Compact. West Slope water users could easily see their future getting squeezed dry between downstream obligations and trans-mountain diversions.

At that point in Colorado’s history, however, the Western Colorado Protective Association did have one powerful card in the hole, a minority’s best argument against term limits: the West Slope’s representative in Congress, Edward Taylor, had been returned to that seniority-driven organization 14 times by 1935. He advanced to the chairmanship of the House Appropriations subcommittee that controlled Interior Department funding – and House rules gave him virtually autocratic authority over that department’s budget.

Congressman Taylor laid down the law according to Taylor immediately upon the commencement in 1933 of East Slope discussion of trans-mountain diversions. Any trans-mountain diversion plan requiring federal assistance, he proclaimed, would have to include, for every acre-foot of water diverted, one acre-foot of “compensatory storage” on the West Slope, for the West Slope’s future needs. This was not just pork-barreling; he made it a moral issue. He proclaimed that no one should build their own future by taking away another’s.

The Denver Water Board, with its concentration of Colorado people and money to draw on, could afford to ignore Taylor’s mandate. They didn’t need federal assistance – although they gladly accepted it when their former engineer, George Bull, became PWA administrator for Colorado and tossed a million-dollar grant and low-interest loan their way for the “shovel-ready” Moffat Project, already under construction. Recognizing Denver’s degree of independence, Taylor graciously exempted municipal water for “our capital city” from his mandate “because it has absolutely got to have that water in order to make the future development and growth that we all hope Denver may have.”

Taylor also nipped in the bud the Arkansas basin’s sketchy early ideas for beginning diversions from the Gunnison basin. They were looking to Taylor Park, a big snow accumulator with a perfect reservoir site at the top of the Taylor River canyon. But Congressman Taylor had been trying for a quarter-century to get congressional appropriation for a long-planned reservoir there to “complete” the Bureau of Reclamation’s Uncompahgre Valley Project, taking water through a five-mile tunnel from the Gunnison River deep in the Black Canyon to the rich but water-short Uncompahgre River valley between Montrose and Delta; the reservoir had been planned ever since Taylor’s 1908 ascent to Congress, to be late-season water for the Uncompahgre farmlands.

At the same 1933 meeting in Denver where Taylor granted Denver a pass on compensatory storage, he warned the Arkansas basin away from any idea about Taylor Park – a discussion that got pretty heated. Then, he went directly to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, who was not a fan of trans-mountain diversions, and talked him into finally appropriating money for Taylor Dam to finish the Uncompahgre Project. That left the Arkansas Basin with relatively easy access only to the much drier Tomichi Creek valley south of Taylor Park, or the Roaring Fork-Fryingpan watershed north of it.

That same year, 1933, a group of Arkansas basin irrigators began the Twin Lakes Tunnel from the Roaring Fork with a PWA loan, to much belated but ineffective consternation from Congressman Taylor and the West Slope Protective Association. But the real prize, Taylor Park, would not emerge again in East Slope diversion plans until the late 1980s.

The founders of the West Slope Protective Association knew, however, how ephemeral that power that Taylor wielded was. He was already in his seventies, and would not be controlling the Interior Department budget forever – although, as will be seen in Part 2 of this story, some of his constituents actually seemed to believe he might live forever. But the WCPA figured they had just a few years to try to get something resembling Taylor’s mandate of “an acre-foot for an acre-foot” formalized as a state policy.

After two years of increasingly frustrated back-and-forth across the Divide under Taylor’s watchful gaze, Edward Foster of the State Planning Commission got statewide water leaders together in 1935 as a “Committee of Seventeen,” and they hammered out what came to be known as “The Delaney Resolution,” after Glenwood Springs attorney and WCPA leader Frank Delaney. The Delaney Resolution was a compromise on the Taylor acre-foot mandate. The West Slope would not oppose a trans-mountain diversion if the diverting organization(s) would build compensatory storage of sufficient size to assure future West Slope development that would otherwise be eliminated by the diversion. That would require a thorough study (probably by the Bureau of Reclamation) to determine how much compensatory storage would be needed, but it would almost certainly be considerably less than Taylor’s “acre-foot for an acre-foot” demand.

This Resolution might have been nothing more than a rock in the river of inevitability, around which the flow of eastward diversion would have flowed unimpeded, had the Bureau of Reclamation not embraced it. The Bureau was eager to build the big trans-mountain diversion from the Colorado River to the South Platte Basin that we know as “the Colorado-Big Thompson Project” – but only if the whole state embraced the idea. Since no in-state Reclamation project would be possible without that broad support, the South Platte irrigators finally bought into the idea that they could only invest in their own future by also investing in the West Slope’s future as well.

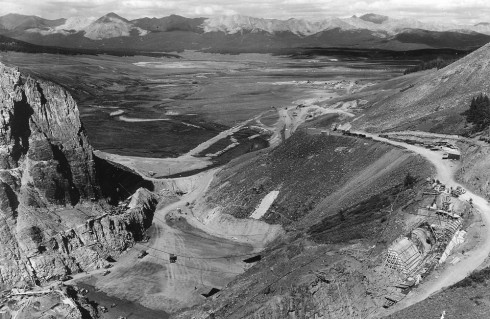

The Delaney Resolution was thus incorporated into an important agreement, Senate Document 80, which was, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, realized in the construction of Green Mountain dam, reservoir, and powerplant on the Blue River. These formed the first element of the massive Colorado-Big Thompson Project, and the West Slope’s protection for the future from that trans-mountain diversion.

Would other East Slope water users, like those in the Arkansas Basin looking lustfully at West Slope water, adhere to the Delaney Resolution? Stay tuned; next month we will look at the fabled Gunnison-Arkansas Project, and why it never happened …