Article by Margery Dorfmeister

Buena Vista Geology – September 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

THAT’S NOT THUNDER you hear rolling off the mountains around Buena Vista. Nowadays, it’s more likely the rumble of rocks rolling off the bucket of a huge front-end loader into a semi dump truck. For generations, Buena Vista’s huge boulders have distinguished the town as surely as her Old Court House steeple. But with the present spate of building going on, her boulders — like her once prime lettuce heads — are being harvested for exportation.

Rocks poking up from the ground or lolling around on the surface were taken for granted on this graben known as the Upper Arkansas Valley. According to geologist, John Groy, the boulders were deposited here by the Nebraskan Glacier during the Quaternary period. Alluvium erosion continued pushing them to the east side of the valley where they’ve happily huddled together…. until recently when they began to be taken for granite.

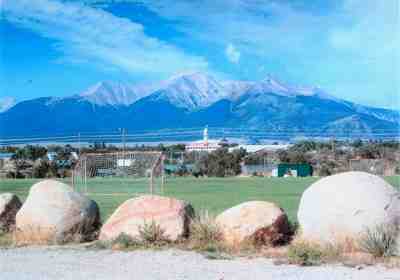

During the development of Buena Vista’s River Park in the 1990s their bothersome presence was solved by rolling many of them off the intended pathways and lining them up along the edges of the soccer field where climbing on them is a favorite pastime of young spectators. Park planners also capitalized on them by dumping many into the Arkansas to create a kayaker’s play wave just north of the footbridge leading to the Barbara Whipple Trail.

Since then, they’ve become increasingly mobile. Where once quaint, little Bewnie’s boulder population out-numbered its body count, the ratio is rapidly equalizing. Topless tanker trucks lumber over county roads toting tons of boulders out of town daily from wherever a backhoe tears into the terrain. The closer you get to the Arkansas River, the thicker the boulders — as anyone in the land development biz will tell you. Not since the Colorado Gold rush has the town seen such an exodus of igneous matter. Tourists have always lugged rock specimens home to adorn mantels and gardens, including our quartz crystals, almandite garnets, smoky quartz, aquamarine, and topaz — not to mention the remains of chert tools scattered around by the Ute Indians. But it’s a recent revelation that people living elsewhere covet these smooth, juvenile-elephant-sized hunks of granite enough to truck them long distance for landscaping places where rocks don’t grow like trees.

A local construction company (ACA) has been brokering rocks for the owners of the South Main Project (Jed and Katie Selby) who are in the process of building the country’s largest water park on the Arkansas River next to their planned high density housing development. An ACA spokesperson says 2500 tons of the smaller sized (3 ft.) boulders have already been shipped to Denver for residential retaining walls and other lawn features. Another company is taking excess rocks in exchange for needed gravel and sand.

Even after disposing of quantities of them in the building of their watery playground in the Arkansas, the Selbys still face a surplus of granite. “We are trying to think of creative uses for it,” Jed says. He envisions boulders being carved into statues, granite sinks and tubs, table tops, signs and markers. The River Run subdivision, next door on South Arizona St., has already led the way with clever signage made from their oversized rocks.

Boulders are the bane of Bewnie builders and homeowners. They won’t be ignored. They must be confronted. If they are multi-ton rocks and deeply implanted in the earth, you might even wind up incorporating them into the structure, as John and Jean Dilatush did when they bought the old Buena Vista Hotel on East Main Street and turned it into Buena Vista Square 25 years ago. While adding an annex for shops and offices, they confronted a voluminous rock deeply imbedded in their backyard. “I believe it was a matter of economics that we decided not to remove it.” John says. Contractor, Chuck Kay, who planned and oversaw the construction, confirms that recollection. “It would have been too costly to blast the rock out of the ground. To tell you the truth, we weren’t sure it could even be done. So we built the staircase over and around it, epoxied the edges, and ran the carpet up against it,” he says, adding that the town’s building department was in it’s baby stage then. “I doubt we’d be allowed to do that today.”

That particular rock remains today as a point of pride to the Courtyard Gallery owners — nine Buena Vista women artists who run a co-op, featuring the works of local artists as well as selling art supplies. “People often come in to admire the rock.” they say. The attention given their centerpiece amuses Nancy Locke, who grew up in a house on Cedar Street with a backyard adjoining the Buena Vista Square complex. Nancy and her friends used to play on the rock. “When I was about six years old and small for my age, my foot caught in a crack in the rock. I can’t remember how they got me out, but they were never able to get my shoe out.” So Nancy’s shoe remains sealed off in one of Buena Vista’s natural wonders until the next climatic climax in the valley shakes it up and spews it out.

It’s comforting to know that Buena Vista’s celebrated Elephant Rock is unlikely to be moved by this surge of growth. Photos taken a century ago show its neck exposed. Now buried up to its ears in the ever-drifting detritus, it is more in danger of being submerged by recurring pressure to build a reservoir. Like any normal landmark, it’s subject to periodic vandalism, but remains firmly planted north of the railroad tunnels, themselves a masterpieces of granite sculpture.

Margery Dorfmeister is a long-time Buena Vista resident and a recovering free-lance writer who backslides occasionally.