Article by Ray James

Christo – July 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

Don’t call them ephemeral.

Sure the major art works of Christo and Jeanne-Claude last only a few weeks but it takes years, sometimes decades, of designing, planning, gaining permission, and constructing to implement their artistic visions. Just such a vision is the “Over the River Project for the Arkansas River, State of Colorado,” the working title for a project that — if it happens — would fling sheets of fabric along stretches of the Arkansas River between Salida and Cañon City. There’s substance, too, in the millions of dollars the project has cost already and the millions more it will cost if it’s to become a reality.

At a presentation this spring, the artists were there to talk about their work. Or rather here, in Austin, Texas, as the case was on a steamy late March night. The chance to hear Christo and Jeanne-Claude talk about their art and a river I hold dear enticed me from my graduate student’s garret. I saw it as a chance to get closer to the Arkansas in Colorado, without leaving the banks of the Colorado in Texas.

Weird, huh? Well, this city’s motto is “Keep Austin Weird.” No, really, I’m not joking.

My main mission at the Christo and Jeanne-Claude lecture was to listen for dishonesty. Were the artists saying one thing in Colorado and something else on the road?

The short answer is, “No.” Based on what I’ve read about ChristoandJeanne-Claude’s (that’s how she says it should be said, “one word”) previous public comments in Colorado, and what they said before a crowd packed into downtown Austin’s Paramount Theater, the only element that might be different is the shade of red in Jeanne-Claude’s hair.

Christo’s Bulgarian-blurred English and Jeanne-Claude’s chirpy French accent are the same here and there. Christo’s off-grey, multi-pocketed safari jacket is the same. Her offbeat humor and his intensity are the same. What may be different about Christo and Jeanne-Claude deep in the heart of Texas as opposed to up in the Heart of the Rockies is their eagerness to talk about the Over the River process.

The artists also dropped an aside about the people in Salida, which made it clear that protest won’t sink the project. Failure to get permits, yes; protests no.

The artistic duo swapped places on and off the microphone to tell enthralled Texans about their art. The enthusiastic audience oohed and aahed throughout a 45-minute slide show with running commentary from the artists, who sat on the edge of their chairs in the shadows stage right.

THE SLIDES AND DIALOGUE revealed insights into the design, engineering, and permitting processes for Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work in progress as well as some of their past accomplishments. One slide nestled among many which showed Christo and Jeanne-Claude doing dog-and-pony shows for city, county, state, and/or federal officials, flashed an image from 20th-century Salida. It showed a packed house at the Salida Senior Citizens Center — the “First Citizens Center,” I used to call it — sometime in 1993 when Christo and Jeanne-Claude came to town to wow the locals and generate support. During the slide’s brief time on the screen, I recognized faces among the crowd.

Christo said, with a dismissive flip in his voice, that many in that crowd, and in the town, were “aging hippies.” (Maybe they were hidden behind the entrenched Salida Old Guard, in chairs, and the new-wave artisans and freethinkers, on the floor.)

When the artists appeared in Salida more than a decade ago, I imagine people were intrigued by these strangers who wanted to spend millions — people probably liked that thought — and bring hundreds of thousands of tourists to see fabric stretched over the Arkansas River. Huh? Someone, or perhaps several someones, must have asked, “Why? What’s the value in that? What’s its purpose? Is that art? What about the traffic jams on Highway 50? What about the sheep and deer looking for a drink?”

During the question-and-answer period that followed the slide show in Texas, Christo and Jeanne-Claude answered similar questions with replies at times succinct and by turns impassioned. Neither ever answered my question (during the intermission each person could write out only one question to submit for consideration) which was: “What level of public protest would be enough to stop the Over the River project?”

THEY DID, however, answer my question indirectly in a number of comments about resistance to their previous projects. And, yes, for those who are curious, some of the artists’ proposals have failed to happen. Christo puts the number at 37, while Jeanne-Claude said 30 projects have been left on the drawing boards because of failure to get official permission.

It should be noted that the Wrapped Reichstag project in Berlin took 24 years to complete. Changes in administrations and political winds have allowed their projects to move from on-hold to reality. That’s what happened in New York with The Gates (2005). Michael Bloomberg, a fan, got elected mayor and cleared a path through Central Park for the project.

Asked how they could have so much patience, Jeanne-Claude responded, “It’s not a matter of patience, it’s a matter of passion.”

Asked how they responded to their critics (of The Gates in particular), she tossed the question aside and quipped, “We don’t.”

Christo explained his work and the reason resistance to Over the River may prove futile: “This is a work of art. It has no purpose. If there are 1,000 who try to stop it and 1,000 to help, it creates energy, it adds to the dynamic. Time builds the power of the work.”

It occurred to me, about halfway through the show, that the fact that 1,300 people from Central Texas paid either $42 or $20 a seat — 650 at each rate — to see Christo and Jeanne-Claude show slides and to hear the artistic duet answer questions about their work, indicates the different degree of sophistication between the people down here and those up there. Sophisticated city people pay good money to do what mountain people do for free.

Back in 1993 nobody in the Upper Arkansas Valley paid to see and hear Christo and Jeanne-Claude talk about their art, but they probably saw a similar show. Of course, the 1993 slide show didn’t have images of the Wrapped Reichstag (1995) and The Gates in New York’s Central Park, still 12 years in the future, and it lacked all those pictures of the official meetings on Over the River in Salida, Cañon City, Denver, and Washington.

If all of the government units involved issue the permits Over the River needs, Christo said that the fabric will be “living, moving with the wind” for 14 days in the period between July 15 and Aug. 15, 2009. That will be 24 years after the seed for the project was planted. {Editor’s note: That was before it was decided the project needed a full EIS, which could delay things for a year or more, even if the results are favorable.]

The idea for Over the River was born while the two artists supervised the wrapping of Paris’ Pont Neuf (a bridge) from a boat on the Seine. A panel of fabric drifted over them and, Jeanne-Claude said, they looked up at the sunshine and clouds through the fabric, and glanced at each other as if they shared a thought. Neither spoke.

In 1992 that thought blossomed and Over the River began as a journey through the Western United States. Along with their engineer, they drove over 50,000 miles and looked at 89 rivers. After narrowing their search to six rivers in five states, including the Rio Grande in New Mexico, they chose the Arkansas because it had a highway on one side, a railroad on the other, and banks generally unobstructed by trees.

Only two questions the artists read and answered in Austin reflected concerns that have been expressed in Central Colorado. One was asked by “Blanca,” and referred to the project’s interference with animal habitat.

“Our projects have never hurt even one single cockroach,” Jeanne-Claude replied, and added that she and Christo expect the expensive environmental studies underway to prove that the project won’t harm the wildlife along or in the river.

SOMEONE ELSE ASKED what would prevent some idiot from walking on the cables and jumping on the fabric. Christo said he had friends who had successfully tested other projects by doing just that.

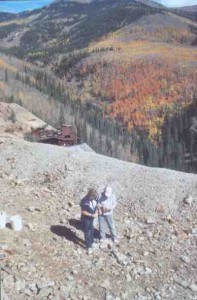

“You could do that,” Christo said with a laugh. The artists said that the engineering for Over the River has checked out. They showed images of fabric, mounted on cables, across a river in Colorado. Christo refused to say exactly where it happened or when but said the crew conducted the test on a stretch of a river that runs through private property.

The day before Christo & Jeanne-Claude’s lecture I visited the Austin Museum of Art, sponsor for the artists’ visit, to get a sense of their work. AMOA’s main floor gallery displayed the Würth Museum Collection of their work. The items included a violin, a book, chairs, tables, and armchairs all wrapped in fabric and other materials then tied with rope or twine. At the lecture the following night Jeanne-Claude emphasized a number of times that they don’t do “wrapped” anymore (so enough with the jokes and stereotyping already). The Reichstag wrap was the last such project, and occurred after they stopped wrapping because it took so long to get the OK to do it.

Collages — really elaborate preliminary sketches of their larger projects before they’ve reached fulfillment — occupied walls throughout the AMOA space. Two collages of Over the River filled one wall near the rear. The top panel of each looks like an enlarged section of Geological Survey map and the bottom, larger sections held a color sketch of a sere river valley with silver-blue fabric running through it, and a river with rocks and fabric over it. Clouds can be seen through the cloth. Both are dated 1993.

The staff was unfailingly polite — this is Texas. From the bustling red-head at the front desk to the public relations director, they considerately managed to stonewall every one of my efforts to get a good Christo picture or to ask a meaningful question of the artists.

I really wanted a picture of Christo and/or Jeanne-Claude holding the March issue of Colorado Central — the one with the “Christozilla” cover — but “no way.” An interview? “No.” Ask a few questions. “No.” It seems all press availability had been restricted to “media who can help us promote the event.”

CHRISTO AND JEANNE-CLAUDE may not be wrapping anymore, but the staff at AMOA certainly did during the artists’ visit. They kept Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped up. They allowed no photographs at the lecture or at the two-hour book-signing the following day. Christo and Jeanne-Claude did hit some other venues while in Austin but I don’t run in those circles. Paying $500 for the main event ball or $75 for an “after party” ticket? I wish.

Besides, there was no guarantee of getting a picture. And afterwards I didn’t see any images in the local media either.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude have moved on. Their recent traveling exhibit was scheduled for five stops besides Austin: New York; Miami; Portland, Maine; and Fresno, California. Presuming all of them are as lucrative as Austin, the enormous funds needed for Over the River are coming in.

Here’s the bottom line: If Christo and Jeanne-Claude and their crew of paid, “mostly local” workers finish installing the supports, cables, and seven miles of Over the River fabric along the Arkansas and then start to tear it all down two weeks later, you can blame a bunch of sophisticated Texans (New Yorkers, Miamians, Portlanders, and Fresnites) if you hate the project. And if you love it, you can praise the same bunch.

Jeanne-Claude said that getting permits and ignoring protests are all part of the process; they are part of the artwork. That means that Christo and Jeanne-Claude are just the chief artists, and everyone else involved in promoting or fighting Over the River are also artists — just slightly less well-known.

And you know that old saw: you can never be too rich, too thin, nor have too many artists.

Ray James created works of journalistic art here in Central Colorado over the years, but now lives in Austin, Texas, where he attends graduate school.