By Duane Vandenbusche

The date was July 14, 1878, and Nicholas Creede was tired. The veteran miner from Indiana had been prospecting for two months in the South Arkansas River country and had found nothing. Then, about five miles east of a high pass, he hit a promising strike and named it Monarch. The discovery of the Monarch Mine led to a mining frenzy as hundreds of miners flocked in during the Spring of 1879. Creede left the South Arkansas area early, and a decade later found great silver deposits near the head of the Rio Grande River. The great mining camp of Creede grew up there and was named for him.

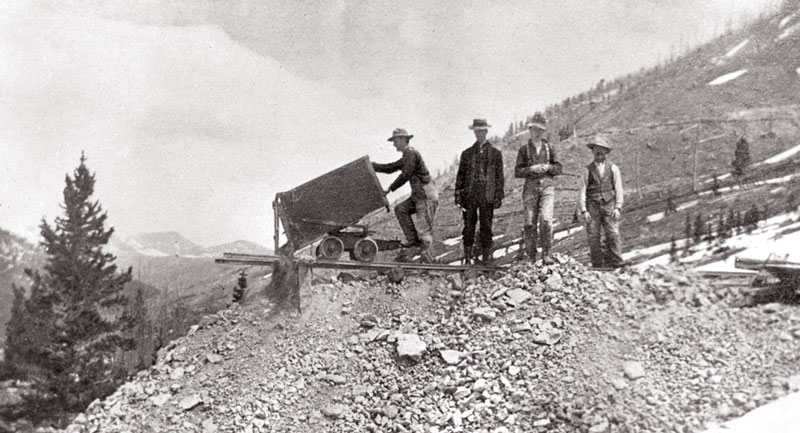

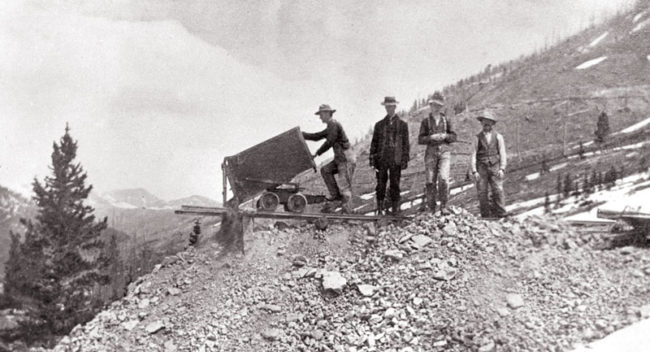

The mining camp that sprang up along the South Arkansas River was first called Chaffee City after millionaire mining man Jerome Chaffee, but soon was named Monarch after the mine discovered by Creede. By 1883, Monarch, 10,018 feet in the clouds, had 2,000 people in camp and the great Madonna Mine had been discovered. The Madonna was 11,000 feet high, 1,000 feet above Monarch, and an aerial tram 2,376 feet long, carried ore from the mine to the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad tracks below. The Rio Grande had laid tracks up the South Arkansas River to Monarch in 1881 to tap the rich silver mines which had opened. The great Madonna Mine produced more than $5 million dollars in silver, gold, lead, copper and zinc in its first decade – over $50 million by 2018 prices!

Monarch was a great mining camp by 1883. It had prolific silver mines with the Madonna, Monarch, Eclipse, Magenta and Oshkosh, a railroad, smelter and wealthy investors coming in daily. The camp also had 125 houses, a post office, three hotels, three stores, a mining exchange, three assay offices, the Eureka Dance Hall, Ozmans gambling casino, three restaurants – the Saddle Fork, Welcome House and Katie Finn’s, three saloons – the Arcade, Miner’s Exchange and Last Chance, and Bill Cord’s famed Palace of Pleasure. The Madonna Mine alone shipped 120 tons of ore daily. The Denver and Rio Grande ran 237 miles from Monarch to Denver, with a passenger fare of $11.10. Sixteen-year-old Anne Ellis described Monarch in the 1880s as, “Another mining camp – a very picturesque one, the mountains rising very high and so straight it seems impossible for the miners to keep a foothold going to or coming from work. Down in the gulch, far below the mines but in sight of them, is a little mining camp running along either side of the river. Most of the homes are log cabins.”

Monarch remained a thriving silver camp until the Silver Panic of 1893, when the plummeting price of the metal closed silver camps across the West forever. Monarch collapsed in that year as mines closed, smelters shut down and investors stopped coming. The population drifted away, and as the years went by, buildings collapsed from heavy snow and roaring avalanches, including a major one on February 3, 1907, which roared down Snowslide Gulch and killed seven. By 1924 only a few people remained in the once great camp. Monarch, however, had a few more cards to play. The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company of Pueblo (CF&I) needed lime to help produce steel in the Pueblo mills and in the late 1920s bought the Eclipse limestone quarry at Monarch. With coking coal from Crested Butte, lime from Monarch, and molten iron, the CF&I combined all three in a blast furnace to produce steel and helped fuel the United States’ industrial revolution.

From 1881 to 1956, Rio Grande tracks to Monarch were narrow gauge (three-feet wide). That meant that the lime in the narrow gauge cars from Monarch had to be transferred to standard gauge cars (four foot, 8 1/2 inch) in the Salida rail yards for the trip to Pueblo. The transfer was made by a machine called a barrel roller which picked up the narrow gauge cars and turned them upside down, dumping limestone, coal or other materials into a standard gauge car. In 1956 the rail line was converted to standard gauge. The D&RG stopped running to the limestone quarry in November, 1981. Today, the Colorado Limestone Company still mines the limestone.

In 1963, two women from Rockford, Illinois – Marion Whittle and Geraldine Stafford, began building a three-story ski lodge at Monarch near the limestone quarry. They ran out of money and the lodge was never finished. A decade later, a huge wind blew it down – a dream unfulfilled. The Madonna Mine closed for the final time in 1953, but it still had one more ace to play. Elmo Bevington, owner of the Monarch Lodge, Monarch Crest and Monarch Ski Area opened it again in the 1960s and ran tours on an electric tram 2,500 feet into the mine. There were tours every 30 minutes for $2. There was even a museum in the mine. Bevington was forced to end his operation in 1980 when the Environmental Protection Agency closed the mine because of the presence of radon gas.

The great days of Monarch are now in the distant past, but the little mining camp high in the Rocky Mountains played a major role in the railroad, mining an steel history of Colorado.

Duane Vandenbusche, a professor of history at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison since 1962, is the author of several books on the Gunnison country and Western Colorado.